A Divine Project

Elijah Mvundura March/April 2014In Wallace v. Jaffree (1985) the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote that the “wall of separation between Church and state ” was a “metaphor based on bad history, a metaphor” that “should be frankly and explicitly abandoned.” The history Rehnquist was referring to is of the formulation of the metaphor by Thomas Jefferson and the deliberations surrounding the religious clauses of the First Amendment. In America the church-state debate has revolved mainly around the U.S. Constitution. Marginal to the debate is the church’s foundational text, the Bible.

This is anomalous. The church was born of the Word, separate and distinct from any national or political institution. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) perceptively pointed out, “Jesus came to establish a spiritual kingdom on earth; this kingdom, by separating the theological system from the political, meant that the state ceased to be a unity, and it caused those intestine divisions which have never ceased to disturb Christian peoples.”1 Again, as Pierre Manent stressed, the unique trajectory of Western society “is understandable only as the history of answers to problems posed by the Church, which was a human association of a completely new kind.”2

Disestablishment or separation of church and state was the American Founding Fathers’ solution to the theologico-political problem. But it’s a solution, to paraphrase Karl Marx, which they did not make just as they pleased, under circumstances they had chosen, but under circumstances directly found, given, and transmitted from the past.3 The direct circumstances were the sheer multiplicity of religious sects, which made establishment of any one church problematic. The near past was the English Civil War, which cast a long shadow over colonial America’s social and political thought. The distant past was the Protestant Reformation, which shattered the unity of Christendom, producing numerous sects and religious wars. The far distant past was the gospel, which inspired the Reformation. And the gospel, as we know, is deeply rooted in the Hebrew Bible and the history of ancient Israel.

If the Bible is the primary text for those who have aspired to build a divinely ordered society or Christian nation, then it is paradoxical that they have blithely overlooked the founding principles of the nation of Israel instituted at Sinai, principles which have a distinctively modern ring. “The Mosaic Code,” as Max I. Dimont acutely observed, “laid down the first principles for the separation of church and state.”4 First, following the advice of his father-in-law, Moses selected judges to preside “over thousands, hundreds, fifties and tens”; and to bring difficult cases to him (Exodus 18:17-27).5 Then following God’s word, he instituted the priesthood under Aaron and his sons separate from his civil leadership (Exodus 28:1). All in all, there was at Sinai a separation of judicial, priestly, and political offices that uncannily mirrors the separation of powers by the American Founding Fathers 3,000 years later.

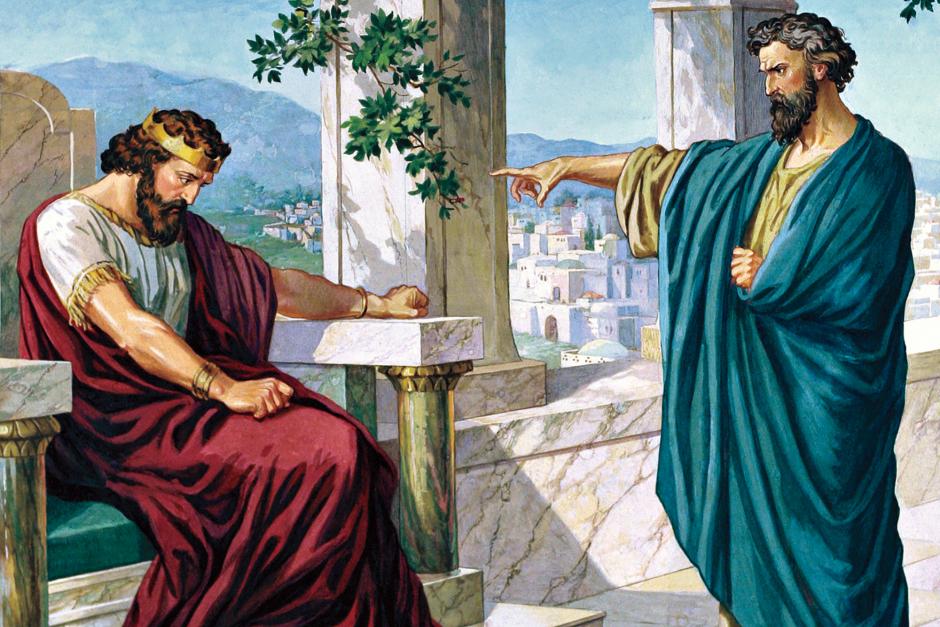

And the separation of priestly and political offices remained sacrosanct even after the establishment of the monarchy. Saul, Israel’s first king, and Uzziah, king of Judah, were deposed for officiating as priests (1 Samuel 13:4-14; 2 Chronicles 26:16-18). In fact, the Mosaic code had limited the monarchy by subjecting it to God’s Law (Deuteronomy 17:14-20). Thus, Nathan’s rebuke of David (2 Samuel 12:1-14) and Elijah’s of Ahab (1 Kings 21) were pointed repudiations of royal absolutism. Apparently, the temptation to absolutize or sacralize the monarchy was present in Israel. The prophets challenged this. Emerging at different times in Israel’s history, speaking for God, while standing separate from the altar and the throne, they fearlessly condemned and checked idolatric practices that threatened to erase the distinction between the religious and the political, the scared and the profane.

To be sure, the tension between the religious and the political, in particular the alliance of the altar and the throne in leading Israel into apostasy, is what caused the prophets to divorce the fate of the nation of Israel from the divine purpose in history. As they said, in spite of the Babylonian captivity, a faithful remnant will survive and consummate the divine purpose in history.6 And the captives that returned from Babylon did jettison political and ethnic aspects of their identity. Calling themselves the remnant, they organized themselves as a religious community (Ezra 3:8; 9:13; Haggai 1:14). This shift from a politico-ethnic to religio-ethical identity was of epochal significance. It set ethical monotheism on its world-transforming career, earning Jews the ire of pagan elites.

The crux is that ethical monotheism subverted the “peace of the gods,” the ideological basis of Greco-Roman imperialism. That is why in antiquity Jews gained notoriety as “a race remarkable for their contempt for the divine powers.”7 Yet they won so many converts and sympathizers that Seneca (Nero’s tutor) fulminated, “The customs of this detestable race have become so prevalent that they have been adopted in almost all the world. The vanquished have imposed laws on the conquerors.”8 This vituperation explains Roman prohibition of Jewish proselytizing and violent response to aggressive Christian evangelizing.

This sharp conflict between the Greco-Roman and the Judeo-Christian must be underscored, because it has often been understated or ignored. But as Leo Strauss argued, given this sharp conflict or “radical disagreement,” as he put it, “a closer study shows that what happened, and has been happening in the West for many centuries, is not a harmonization but an attempt at harmonization. These attempts at harmonization,” which Strauss averred, “were doomed to failure,”9 go to the heart of the Church-State debate, because in the emperor cult or in Caesar’s role as the pontifex maximus (chief priest), the Greco-Roman tradition united priestly and political roles, which, as we have seen, were separate and distinct in ancient Israel.

And the emperor cult did not unite just the political and the religious, but the human and the divine. In other words, it united and embodied in Caesar what the gospel united and incarnated in Christ. To be sure, the God-man Christ fused (without con-fusing) in His person what paganism con-fused mythically and personified in the figure of the divine king, the priest-king, or the pontifex maximus. Significantly, in contrast to the man-god Caesar, the God-man Christ, by “taking the very nature of a servant” (Philippians 2:7), united heaven and earth, the human and the divine, not at the top of the human pyramid, but at the bottom, just like any other ordinary human. “He was,” as Marcel Gauchet acutely observed, “the perfect counterpart to the imperial mediator, only at the opposite pole.”10

The God-man’s servanthood inverted the Roman hierarchy, flattened it. This sowed the seeds of human equality. As Paul memorably put it, “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male or female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). The story of how the seed ideas of equality, freedom, humanitarianism, science, democracy, and capitalism reside in the gospel has been told differently by such greats as Hegel, Tocqueville, Nietzsche, Max Weber and most recently by Marcel Gauchet, René Girard, and Charles Taylor. But the story has not received its due, partly because of the failure or unwillingness to grasp the “radical disagreement” between the Greco-Roman and the Judeo-Christian, in particular the Greco-Roman foundations of the medieval church-state.

Besides inheriting the Roman legal-administrative apparatus, the medieval church-state embraced the Neoplatonic Great Chain of Being. According to its classic formulation in the mystical theology of Pseudo-Dionysius, the celestial hierarchy of angels paralleled the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Descending from God to the least inanimate object, it connected God, angels, humans, and nature in a single all-embracing cosmos. Again, as said, the hierarchy of angels arranged under one head: God, mirrored the clerical hierarchy arranged “under one supreme pontiff. . . . There was therefore, strictly speaking, a single church of angels and of men.”11

The unnoticed scandal is that while taken as Christian, as a replication of the divine order, the medieval hierarchy was in fact a replication of the pagan hierarchy or a reconstruction of the pyramid that Christ had inverted and flattened. Then again, by conjecturing celestial intermediaries of angels and saints, the medieval church-state displaced Christ as the “only mediator between God and mankind” (1 Timothy 2:5), diluted his exclusive redemptive-mediatorial role, and diminished his unqualified pre-eminence in creation over every cosmic power, as expressed in Colossians 1:15-20; 2:18.

Again, we must recall that the construction of the medieval church-state would not have been possible without a radical shift, effected by the Church Fathers, from the temporal-eschatological dualism of the gospel to the spatial-ontological dualism of Greek philosophy. As it is, temporal-eschatological dualism forecloses giving any substantial structure to the kingdom of God on earth. As Gauchet duly stressed, “For Christians, mediation has occurred definitively in the person of the Word incarnate. This is an event that will never have a truly substantial structure. . . . [No person or institution can ever or should] occupy this intersection of the human and the divine. The Son of Man occupied this space historically, and it must remain unoccupied among humans until the end of history.”12

As we know, Martin Luther’s recovery of the doctrine of justification by faith and “the priesthood of all believers” shattered the medieval hierarchy. By positing an unbridgeable chasm between the Holy God and the wretched sinner, Luther’s “theology of the cross” swept away the whole sacramental system: clerical mediation, celestial hierarchy, purgatory, pilgrimages, and a host of other rituals and pieties. In short, Luther restricted mediation to Christ alone. This restriction displaced the throng of angels, saints, and magical intermediaries in the medieval universe.

Accordingly and significantly, “with nothing remaining ‘in between’ a radically transcendent God and a radically immanent human world except”13 this one mediator, Christ, a mechanically, causally ordered universe progressively came into view through the cumulative discoveries of Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton.14 Breakdown of the medieval hierarchical universe also destabilized the political and social hierarchies underwritten by the Great Chain of Being. They became much more difficult to justify in the face of irrepressible egalitarian-democratic ethos inadvertently unleashed by the Protestant Reformation.

This was particularly so in England and the Netherlands, where the victory of Protestantism liberated lay conscience from clerical mediation. But it was in America where, unfettered by traditional hierarchies, the Protestant credo of unmediated access to God inspired a religious revival—the Great Awakening—that helped midwife the American Revolution and underwrite an egalitarian-liberal democracy. This unusual alliance between “the spirit of religion and spirit of freedom” is what greatly amazed Alexis de Tocqueville in the 1830s, a French aristocrat who wrote the most fêted book on American democracy.

“The religious atmosphere of the country,” he wrote, “was the first thing that struck me on arrival in the United States. The longer I stayed in the country, the more conscious I became of the important political consequences resulting from this novel situation.” For whereas, “In France, the spirits of religion and of freedom [were] almost always marching in opposite directions.” In America they were “intimately linked together in joint reign over the same land”15 What made this “intimate link” and “joint reign” so novel is that church and state were separated institutionally. However counterintuitively, separation instead of weakening religion actually made it powerful.

The reason, in Tocqueville’s view, was that separation “restricts [the church] to its own resources, of which no one can deprive it.”16 And these resources, we must stress, are spiritual rather than material, religious rather than political. “Not by might nor by power, but by my Spirit, says the Lord Almighty” (Zechariah 4:6). Paul made the same point. “For though we live in the world, we do not wage war as the world does. The weapons we fight with are not weapons of the world” (2 Corinthians 10:3, 4).

Given how the church has often used “the weapons of the world” and how the gospel has often been, in Tocqueville’s words “mingled with the bitter passions of this world,”17 the wall separating church and state ceases to be a mere metaphor. In fact, given the historical impact of the Bible on Western society, how it separated what paganism united and how these separations define democracy and modernity, the wall emerges as a divine project, the fruit of the gospel seed of human equality. As Tocqueville, describing the irresistible advance of democracy put it, those who fought for and against it were “all driven pell-mell along the same road, and all worked together [as] blind instruments in the hands of God.” And he concluded, “God does not Himself need to speak for us to find sure signs of His will; it is enough to observe the . . . continuous tendency of events.”18

Understanding that modern democracy—its liberation of the individual from hierarchical social orders, its separation of the sacred and the profane, the political and the religious—resulted not from human reason but from divine design is of first importance. It safeguards all power, church or state, from the totalitarian temptation, from the conceit, as John Adams warned, “that it is doing God’s service when it is violating all His laws.”19

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract, trans. Maurice Cranston (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1968), p. 178.

- Pierre Manent, An Intellectual History of Liberalism, trans. Rebecca Balinski (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1995), p. 4.

- Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” in The Marx-Engels Reader, ed. Robert C. Tucker (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), p. 595.

- Max I. Dimont, Jews, God and History (New York: New American Library, 1962), p. 43.

- Scripture quotations in this article are from the Holy Bible, New International Version. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

- Isaiah 10:22; 37:31, 32; Jeremiah 31:7; 42:2; Ezekiel 6:8; 14:22; Joel 2:32; Micah 2:12; 5:7, 8; Zephaniah 3:13.

- Louis H. Feldman, Jew and Gentile in the Ancient World (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1993), p. 152.

- Seneca, in Saint Augustine, City of God, trans. Henry Bettenson (New York: Penguin Books, 1972), p. 252.

- Leo Strauss, The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism: An Introduction to the Thought of Leo Strauss: Essays and Lectures by Leo Strauss, selected by Thomas L. Pangle (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1989), p. 245.

- Marcel Gauchet, The Disenchantment of the World: A Political History of Religion, trans. Oscar Burge (Princeton, N.J. Princeton Univ. Press, 1997), p. 119.

- Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: The Growth of Medieval Theology (600-1300), (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1978), vol. 3, p. 299.

- Gauchet, p. 81.

- Peter L. Berger, The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion (Anchor Books, 1969), p. 112.

- See Peter Harrison, The Bible, Protestantism, and the Rise of Natural Science (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998) and James J. Bono, The Word of God and the Languages of Man: Interpreting Nature in Early Modern Science and Medicine: Volume 1: Ficino to Descartes (Madison, Wis.: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1995).

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, ed. J. P. Mayer, trans. George Lawrence (Perennial Classics, 1966), p. 295.

- Ibid., p. 299.

- Ibid., p. 297.

- Ibid., p. 12.

- John Adams, in Reinhold Niebuhr, The Irony of American History (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2008), p. 21.

Article Author: Elijah Mvundura

Elijah Mvundura writes from Calgary, Alberta, Canada. He has graduate degrees in economic history, European history, and education.