A Kept People

Michael D. Peabody May/June 2016Late last year in Paris and San Bernardino, and then this year in Brussels, the West was violently introduced to the type of terrorism that has plagued the Middle East in recent years. The attacks, carried out by people who had entered France and the United States legally, were a vivid reminder to Americans of the dangers posed by religious extremists.

Even the most stringent security cannot prevent every terrorist attack on the innocent: yet events of this magnitude lead to calls for even more security, even if it comes at the expense of existing freedoms. When attempts to deter attacks on a broad basis fail, the next step is to begin to profile and limit the freedoms of those perceived to belong to the same ethnic or religious group as those who perpetrated the attacks. While this may not seem plausible in 2016, this kind of profiling, which leads to mass internment, has happened before in American history and is legally permissible if precedent is followed. The question of whether the will of the American people favors freedom or security is currently on the table.

The Obama administration maintained that it had strong procedures in place to vet immigrants to ensure that they were not terrorists. The president’s flat response, that the Paris attacks were a “setback” and insistence that ISIS was “contained” and that his plan to destroy them was “working,” did little to decrease the fears and concerns of the people, particularly as Republican presidential candidates used the opportunity to argue that the Obama administration simply did not have the will to truly fight radical Islamic terrorism.

After the Paris attack but before the San Bernardino attacks, the polling group YouGov completed a survey that found that 40 percent of those surveyed supported registration of all Muslims, complete with home addresses, while 49 percent did not. The same poll found that 21 percent would similarly require Christians to register, and 19 percent supported registration of Jews. Fifty-three percent supported registration of gun owners.

A few weeks later the attacks in San Bernardino by an immigrant from the Middle East and her American husband led to an even greater call for a database of Muslims, even as Muslim groups in the United States worked to distance themselves from the extreme actions of a small minority.

The war on terror by its nature has no clearly defined enemies or goals, simply because enemy combatants wear no uniforms, have no clear infrastructure, and hide among the general population. They are impossible to track, and the only major distinguishing factor is religion.

The real purpose or need of a U.S. government database is not clear. Certainly, having the names of all Muslims or members of other groups that could fall within the ambit of paranoia would not be enough. Something needs to be done within the names. If there were further attacks, could people on the list expect knocks at their doors and intense questioning? arrests? internment in a camp?

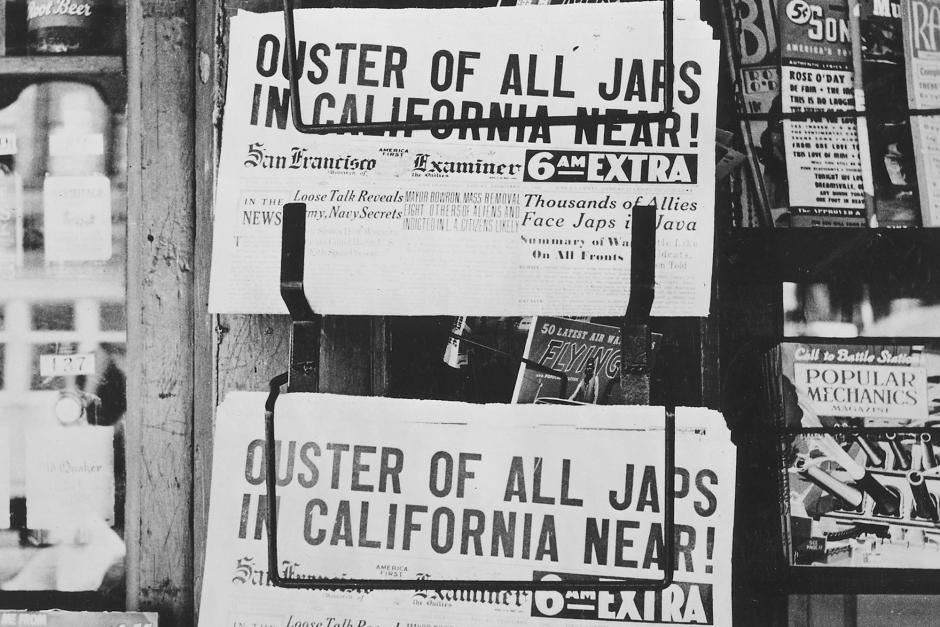

After Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded to pressure from several sources and issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which ultimately led to the forced relocation and incarceration of 110,000 to 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry who lived along the Pacific coast.

Before Executive Order 9066, Roosevelt had ordered that all Japanese, German, and Italian aliens, 14 years of age or over, be registered, and leave the coastal areas. California governor Culbert Olson began the process in early February 1942. The provisions were that identification applications had to be filed with the U.S. Post Office. “No exceptions will be permitted even in cases of aged or infirm aliens, or those aliens living with naturalized sons or daughters in these areas. Entering such areas for shopping, working, visiting, or other purposes is even prohibited under the regulations. Violations of such regulations will result in internment.”2

The way the order worked, regional military commanders were allowed to designate “military areas” from which “any and all persons may be excluded.” This power was used to declare that all people of Japanese ancestry were excluded from the entire West Coast, including California and significant portions of Washington, Oregon, and Arizona. This was implemented during the spring of 1942.

The government obtained neighborhood information on Japanese Americans from the United States Census Bureau, which denied its involvement for more than 60 years, until 2007, when documentary proof was discovered.3

Although the Census Bureau was previously barred from revealing information about specific individuals, the Second War Powers Act of 1942 temporarily repealed that protection.

In 2002 the Census Bureau provided neighborhood data on Arab-Americans to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, but the Scientific American piece quotes Census Bureau chief of the CB’s Office of Analysis and Executive Support as saying this information was already publicly available.4

Appeals to the unconstitutionality of the camps (Roosevelt called them “concentration camps”) did not protect these citizens, and in fact the U.S. Supreme Court issued a 6-3 decision in Korematsu v. United States,5 holding that the need to protect against espionage outweighed the individual rights of Americans of Japanese descent.

In Korematsu Fred Korematsu had refused to leave his home in Oakland, California, and was discovered and arrested. He was sentenced to five years of probation and still sent to a camp. He sued, arguing that his constitutional rights had been violated; the Supreme Court upheld his conviction.

Although the government later apologized, and in 2011 the Obama administration’s Department of Justice conceded that the decision was in error and promised never to use it against citizens in the future, the Korematsu decision has never been overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court. At least in theory, it could happen again.

In a book published in 2007, then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote, “An entirely separate and important philosophical question is whether occasional presidential excesses and judicial restraint in wartime are desirable or undesirable. In one sense, this question is very largely academic. There is no reason to think that future wartime presidents will act differently from Lincoln, Wilson, or Roosevelt, or that future Justices of the Supreme Court will decide questions differently from their predecessors.”6

In 1971 Congress passed the Non-Detention Act of 1971, designed to prevent another executive order, which could lead to incarceration of citizens, by the federal government. The act states, “No citizen shall be imprisoned or otherwise detained by the United States except pursuant to an Act of Congress.” Ruth Bader Ginsburg also wrote in a 1998 dissent that “a Korematsu-type classification . . . will never again survive scrutiny.”

In 2014, during a discussion with law students in Hawaii, Justice Antonin Scalia said that “the Supreme Court’s Korematsu decision upholding the internment of Japanese Americans was wrong, but it could happen again in wartime.”7

On June 29, 2014, the Supreme Court declined to hear Hedges v. Obama, a constitutional claim challenging a law that could enable the indefinite military detention of U.S. citizens without trial, charges, or evidence of a crime. This case represented the latest (hopefully not the last) clear chance that the Court has had to overturn Korematsu.

{image_2)

The legal reality is that a wartime directive that all members of a certain religious sect or ethnic group should register—and that this information could cause them to be held without trial, charges, or evidence of a crime—could be found constitutional despite the fact that it strikes against the core principles of the Bill of Rights. There is real danger here, and it’s not a matter of legality. It’s a matter of likelihood.

The fact that the threat of internment of ethnic groups consistently lurks beneath the surface has not been lost on American politicians. On November 18, 2015, David A. Bowers, the mayor of Roanoke, Virginia, referred back to the internment camps when he called on the suspension of relocation of Syrian refugees to his region, stating, “I’m reminded that President Franklin D. Roosevelt felt compelled to sequester Japanese foreign nationals after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and it appears that the threat of harm to America from ISIS now is just as real and serious as that from our enemies then.”8

We live in a time when the most vague threat of terrorism is enough to create large-scale panic. In December an e-mailed terrorist threat led to a one-day shutdown of the 640,000-student Los Angeles Unified School District at the expense of tens of millions of dollars of revenue. The fear of terrorism crosses political boundaries, and if such attacks were to be carried out just a handful of times, freedoms could be quickly reduced (based on recent responses) as citizens clamor for a sense of safety over constitutional protections.

World history is full of charismatic leaders who gained power by saying things that resonated with the fears and prejudices of the people and yet ultimately led their nations to abandon their most basic freedoms. It is too early to say whether another president would ultimately succeed in implementing a database of Muslims, or whether Congress might order massive incarcerations in the wake of future attacks, but when the first impulse in response to terrorism is to advocate for the removal of fundamental freedoms and rights of an entire religious or ethnic group, this is a danger sign. Those who value the Bill of Rights cannot afford to be silent. This is the time to speak up.

1 In Time, Nov. 19, 2015.

2 A copy of the order in Marin County, California, is available in the Sausalito News, Feb. 5, 1942: “Registration for Aliens Under Way.”

3 www.scientificamerican.com/article/confirmed-the-us-census-b/

4 Ibid.

5 323 U.S 214 (1944).

6 All the Laws but One: Civil Liberties in Wartime, p. 124.

7 Debra Cassens Weiss, “Scalia: Korematsu Was Wrong, but You Are Kidding Yourself if You Think It Wouldn’t Happen Again,” American Bar Association Journal, Feb. 4, 2014.

8 www.roanoke.com/david-bowers-statement-on-syrian-refugees/pdf_54895fc2-dcfa-50a9-9e40-4c382ed7ab4e.html; see also www.cbsnews.com/news/roanoke-mayor-refers-to-japanese-internment-in-statement-about-refugees/

Article Author: Michael D. Peabody

Michael D. Peabody is an attorney in Los Angeles, California. He has practiced in the fields of workers compensation and employment law, including workplace discrimination and wrongful termination. He is a frequent contributor to Liberty magazine and editsReligiousLiberty.TV, an independent website dedicated to celebrating liberty of conscience. Mr. Peabody is a favorite guest on Liberty’s weekly radio show, “Lifequest Liberty.”