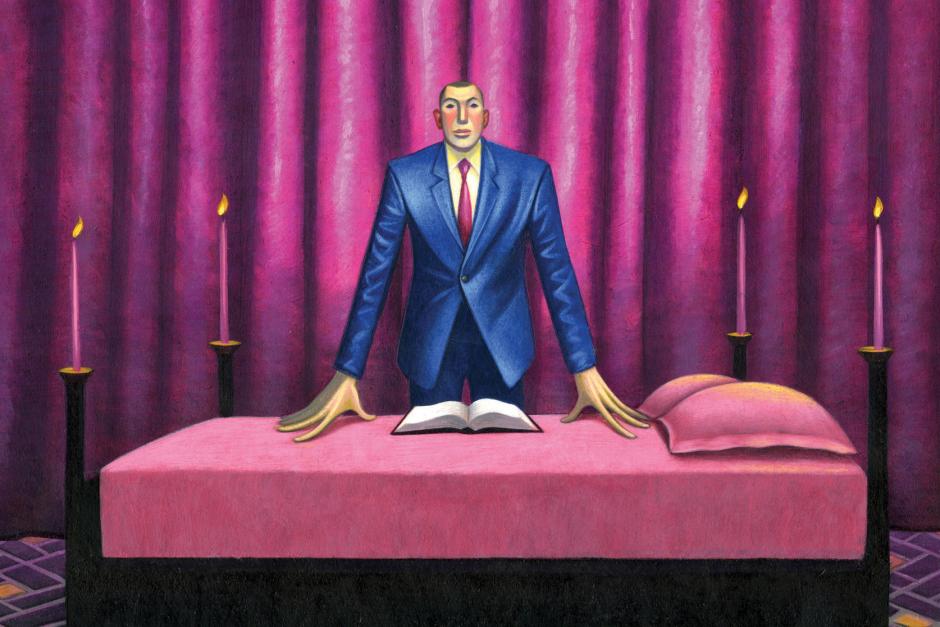

A Swingers Club Gets “Religion”

July/August 2016Since 1965, Goodpasture Christian School (originally East Nashville Christian School) has been, in the words of its current president, Ricky Perry, “a ministry serving the educational needs of families who wish to have godly values and a knowledge of Jesus Christ as the center of their child’s learning experiences.” What started as a few buildings in the 1960s, with about 150 students, faculty, and staff, is now a sprawling campus outside Nashville, Tennessee, with more than 900 students. Goodpasture covers everything from preschool to high school, and though it is affiliated with the Church of Christ, students from various Christian backgrounds attend. Its Website indicates a thriving, multifaceted campus that offers a strong Christian environment.

However, if even God’s original Eden couldn’t escape the intrusion of sin and evil, what chance does Goodpasture Christian School have? The institution has found itself embroiled in a controversy when an abandoned medical building near the back of its property was bought by The Social Club, which dubs itself “Tennessee’s oldest and largest swingers club.” Once word got out, Nashville quickly rezoned the area in a way that would have forbidden the group to exist there.

The rezoning should have ended the issue, except that, in response, “Tennessee’s oldest and largest swingers club” changed itself into the United Fellowship Center. That is, the sex club now claims to be a church, a house of worship, and thus exempted from the zoning exclusion.

Along with the many questions that the courts have grabbled with regarding how far free exercise protections go, the story of the United Fellowship Center adds another dimension: to whom are those free exercise protections given to begin with?

The Hell-conceived Principle of Persecution

Among the myths of America’s founding was that the nation, even before its official inception, had been a bastion of religious freedom and tolerance. That view has remained one of the most consistent, and enduring, revisionist slants on American history. Though having left Europe to escape religious persecution, from the moment the Pilgrims got off the Mayflower, the Bonny Bessie, and other ships,—they showed no intention of granting religious freedom to those faiths not deemed orthodox.

“The much-ballyhooed arrival of the Pilgrims and Puritans in New England in the early 1600s,” wrote Kenneth Davis in the Smithsonian, “was indeed a response to persecution that these religious dissenters had experienced in England. But the Puritan fathers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony did not countenance tolerance of opposing religious views. Their ‘city upon a hill’ was a theocracy that brooked no dissent, religious or political.”

Roger Williams’ famous quest for religious freedom, for example, didn’t occur in England, France, or Spain. Williams was hounded, exiled, and persecuted on the American continent, and his persecutors were fellow Protestants. This incessant intolerance of various Christian sects for each other created the milieu that, ultimately, paved the way for the religions clauses in the Bill of Rights.

It’s not by accident that the first protections in the document, even before the right to bear arms and the ban on “cruel and unusual punishment,” were the nonestablishment and the free exercise clauses. When James Madison warned that “the diabolical Hell-conceived principle of persecution rages,” he wasn’t talking about Roman inquisitors in Spain or Italy, but about Anglicans attacking Baptists in eighteenth-century Virginia. In response to the old religious bigotries carried over from the Old World, a new concept was created for new one: the free exercise of religion, even for those deemed unorthodox, unchristian, heretical.

What’s in a Name?

In the few hundred years since the Bill of Rights, the United States has done an admirably good job in protecting the free exercise of religion. It has been an evolutionary process, with fits and starts, and though the record isn’t perfect (the infamous Smith decision, penned by the late Antonin Scalia in 1990, remains a painful setback), Americans can be proud of how well the nation has protected free exercise.

In one of the most celebrated free exercise cases, Barnette (1943), dealing with the right of Jehovah’s Witness children, based on religious conviction, not to salute the American flag, U.S. Supreme Court justice Robert Jackson wrote: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein. If there are any circumstances which permit an exception, they do not now occur to us.”

However eloquent, those words talk about the freedom offered for, among other things, “religion.” They say nothing, though, about what qualifies as “religion.” Even the Bill of Rights makes no attempt to define religion. Yes, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” That’s great. But as The-Social-Club-turned-The-United-Fellowship-Center controversy shows, the question as to what qualifies as a “religion” remains unresolved. If a sex club, in an attempt to circumvent a zoning restriction, baptizes itself as a “church,” is it now a church, a religion, and thus afforded all the privileges and protections thereof?

Belief in a Divine Being?

For starters, it’s not hard to see why early Americans didn’t define “religion.” There was no need to. “Religion” back then was the Protestant sects, Catholics, Jews, even some Muslims. The definition of the word was, probably, never in question.

Plus, whatever the difference between these faiths, all shared the common concept of a God, the Creator. James Madison called religion “the duty which we owe to our Creator and the Manner of discharging it.” In Davis v. Beason (1890), the U.S. Supreme Court said that religion referred to “one’s views of his relations to his Creator, and to the obligations they impose of reverence for his being and character, and of obedience to his will.” Though dissenting in a 1931 U.S. Supreme Court case, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote that the “essence of religion is belief in a relation to God involving duties superior to those arising from any human relation. . . . One cannot speak of religious liberty. . . without assuming the existence of a belief in supreme allegiance to the will of God.”

Today the United States is the most religiously diverse nation in the world, with thousands (if one counts the various divisions and offshoots from the bigger faiths) of different groups calling themselves a “religion”—everything from Southern Baptists to ISCKON (The International Society for Krishna Consciousness), from Roman Catholics to Nuwaubians. Professor Steven Gey wrote that the “problems associated with defining religion for First Amendment purposes have multiplied in modem times due to the increasingly diverse ethnic and religious character of the population and the equally diverse nature of religious beliefs.”

Also, in a much more pluralistic society than that of Madison or Jefferson, or that of even a century ago, the definition of “religion” has been broadened in ways that don’t even demand belief in a divinity. What does one do, for instance, with Buddhism, which isn’t based on belief in a Supreme Being? In a footnote in a unanimous decision in Torcaso v. Watkins (1961) the High Court said: “Among religions in this country which do not teach what would generally be considered a belief in the existence of God are Buddhism, Taoism, Ethical Culture, Secular Humanism and others.”

Conscientious Objectors

Further clarification of “religion” came in the United States v. Seeger (1965), which dealt with conscientious objection from military service. Section 6(j) of the Universal Military Training and Service Act “exempts from combatant training and service in the armed forces of the United States those persons who by reason of their religious training and belief are conscientiously opposed to participation in war in any form.” The act defined “religious training and belief” as “an individual’s belief in a relation to a Supreme Being involving duties superior to those arising from any human relation, but [not including] essentially political, sociological, or philosophical views or a merely personal moral code.”

No wonder, then, that Daniel Andrew Seeger, an agnostic, was convicted in the District Court for the Southern District of New York for refusing induction into military service. Seeger had declared that he conscientiously opposed to war, in any form, because of his religious convictions apart from belief in a Supreme Being. Instead he based his position on the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and Spinoza in order to support his aversion to all war, but “without belief in God, except in the remotest sense.”

The High Court, however, said that the Congress didn’t use “Supreme Being” to mean “God” in just the traditional sense. Rather it meant the phrase to be understood as embracing “a sincere and meaningful belief which occupies in the life of its possessor a place parallel to that filled by the God of those” who had routinely gotten conscientious objector status. With that line of reasoning, the Court ruled in Seeger’s favor.

Vegans and Wiccans

The issue of defining religion didn’t end with conscientious objectors, though.

Jerold Friedman, an ethical vegan, believed “that all living beings must be valued equally and that it is immoral and unethical for humans to kill and exploit animals, even for food, clothing and the testing of product safety for humans.” When his employer, a hospital, required a mumps vaccine, he refused, arguing that the vaccine was grown in chicken embryos and, according to his belief system, “egg-laying hens suffer greatly in chicken factory farms, and the use of unborn chickens to culture the mumps vaccine causes further unnecessary deaths of chickens.” After informing the hospital of his refusal, he was denied employment.

Friedman filed a complaint with the EEOC in 1999, claiming that his “termination discriminated against him on the basis of his religious views in violation of Title Vll.” The case worked up the California court system, with the Appellate Court deciding against Friedman, even if it did not shut the door to protection from discrimination for all religiously-inspired vegans. Friedman petitioned the California Supreme Court, and the U.S. Supreme Court, though both times his request was denied, which means that for now ethical veganism does not qualify as a religion for the purposes of workplace discrimination law.

In Dettmer v. Landon (1986) the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit heard a case involving a Wiccan prisoner in Virginia, Daniel Dettmer, who wanted access to various ritual objects, including knives, that were part of his Wiccan faith. When prison officials refused, Dettmer sued, claiming a violation of free-exercise protections. The state argued that Wicca was just a “conglomeration” of “various aspects of the occult, such as faith healing, self-hypnosis, tarot card reading, and spell casting, none of which would be considered religious practices”and, thus, Dettmer had no religious liberty grounds for his request.

Though the appellate court rejected the claim that Wicca was not a religion, it still denied Dettmer’s request, arguing that the “decision to prohibit Dettmer from possessing the items that he sought did not discriminate against him because of his unconventional beliefs.” In other words, even if his Wiccan beliefs were bona fide religious, the prison’s refusal to provide knives involved reasons other than religious discrimination.

The United Fellowship Center

As these cases and others show, the definition of “religion”—more than 200 years after the Bill of Rights was created to protect it—remains blurred at the edges.

What, then, of a swingers club that now calls itself United Fellowship Center? As of this writing, The Social Club’s request to renovate its building behind Goodpasture Christian School and convert it into a “church” has been approved by the city. Floor plans show the same basic room layout as the club but with name changes. The “dungeon” will now be for the “choir,” and a dressing room has been converted into the sacristy. The owner has also become an ordained minister, having obtained the ordination online in about two minutes’ time.

As do most churches, the United Fellowship Center has a mission statement. It reads: “We were founded on the basic belief that we are all children of the same universe and, derived from that basic belief, has established two core tenets by which it expects its ministers to conduct themselves.” Those two beliefs are: “Do only that which is right” and “Every individual is free to practice their religion in the manner of their choosing, as mandated by the First Amendment, so long as that expression does not impinge upon the rights or freedoms of others and is in accordance with the government’s laws.” The United Fellowship Center says that “everyone is welcome, whether they come to us from a Christian, Buddhist, Muslim, Jewish, Catholic, Shinto, agnostic, atheist, pagan, Wiccan, or Druid tradition, to speak their own truth to power. The communication and fellowship of our scattered members across the U.S.A., we believe our fellowship is just as valid a form of worship as the weekly services held in some of the world’s more segregated and elitist religious institutions.”

Is this swingers club a “religion” because it now calls itself one and has some of the trapping that, traditionally, come with religion, especially when its Web site, talking about what happens at Fellowship Center, also says: “Meeting Every Weekend With Other Open and Broadminded Men, Women and Couples.” How foolish to think that weekends at the Community Fellowship Centers with other “broadminded men, woman, and couples” consist of prayer, Bible study, and participation in the Lord’s supper. Though this issue has not reached the judicial system (as of yet), what would happen if it does?

“Courts tend to be skeptical of new religions that assert religious freedom claims,” says Alan J. Reinach, executive director of the Church State Council. “If this matter were to get to court, the fact that the club became a religion in order to qualify for zoning would likely weigh heavily in a court’s view of whether it deserves recognition as a bona fide religion.”

Whatever the outcome, Goodpasture Christian School has for now a living example, in its own backyard, of Christ’s warning: “Behold, I send you out as sheep in the midst of wolves. Therefore be wise as serpents and harmless as doves” (Matthew. 10:16, NKJV).*

By Dudley Doright. Dudley Doright is the pseudonym for a serious author, not a member of the club.

*Texts credited to the NKJV are from the New King James Version. Copyright ©

1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.