Afghanistan: The Land That Freedom Forgot

Martin Surridge November/December 2011

The sound and smell of motorcycles roaring down a street in Kandahar must have overwhelmed 16-year-old Atifa in the moments before the attack. Before she really knew what was happening, one of the cyclists approached Atifa, her sister Shamsia, and several other girls and threw acid onto their faces. Atifa’s scarf melted into her hair, and 19-year-old Shamsia lost much of the skin on her face and the temporary use of her eyes, swollen shut from the inflammation.

This tragic story, as well as details of other acid attacks on Afghan school girls, was reported by CNN’s Atia Abawi in January of 2009. Stunned observers around the world learned that the religious extremism in Afghanistan was more violent than many had thought possible. Despite the forty-fourth article of the Afghan constitution specifically promoting the education of women, many Islamists still hold the hard-line views of the Taliban, which from 1996 to 2001 banned even basic female education for being un-Islamic.

Afghanistan has been called a failed state—a nation incapable of governing itself adequately. It is a land marked by systematic corruption, widespread human-rights abuses, and continual violence. Landlocked in the mountains of central Asia and highly dependent on the export of heroin, Afghanistan has been gripped by war, civil unrest, and terrorism for nearly a century. Instead of improving, things there seem only to be getting worse.

Since regaining its independence from the British in 1919, Afghanistan has ousted kings and generals. The country endured and then resisted Soviet occupation in the 1980s, and suffered through a lengthy civil war. The civil war facilitated the rise of the Taliban, who gained power after storming the presidential palace in the capital city of Kabul in September 1996.

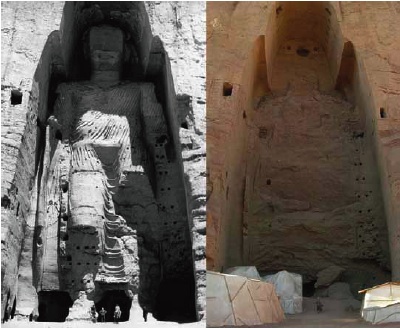

One of the two sixth-century standing Buddhas carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamiyan valley of central Afghanistan. The photo on the right was taken after the statue was destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.

One of the two sixth-century standing Buddhas carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamiyan valley of central Afghanistan. The photo on the right was taken after the statue was destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.

Today Afghanistan is synonymous with oppressive conditions—both for the NATO troops enduring lengthy and dangerous tours of duty in a hostile, arid terrain and for its citizens, living in one of the least tolerant places on the planet. In the summer of 2001, at the height of their power, just months before al-Qaeda terrorists carried out the September 11 attacks that were planned in Afghanistan, the Taliban ordered non-Muslims to wear tags identifying their status as a religious minority and required Muslim and Hindu women to cover themselves with a veil. Additionally, those in power had destroyed several priceless, ancient Buddha statues in the central province of Bamiyan, as international organizations scrambled unsuccessfully to save them from such a fate.

The NATO troops have been fighting a costly and increasingly drawn-out war with the Taliban. But it is more than just set battles and insurgency violence against the military forces. The forces of Islamic extremism and religious tyranny remain and are felt throughout the country. Insurgents lit fires in classrooms, burning down school buildings, in blazes that were deliberately fueled with the papers and exercise books of children. A school caretaker’s face was mutilated, Christian aid workers were murdered, and suicide bombs continued to devastate neighborhoods and kill not just American soldiers but Muslim civilians, too. The stench of religious intolerance—singed flesh, smoldering rubble, scorched textbooks—had become inescapable, burned into the very framework of the nation.

It had not always been this way. What we know now as the ravaged, failed state of Afghanistan, which tolerates only the intolerant, was once home to Amaah Khan, king of the Emirate of Afghanistan from 1919 to 1929. Inspired by reforms in the West, specifically those instituted by Turkey’s leader Kemal Ataturk, Amaah modernized the nation by building roads, hospitals, and schools. He knew that in order to prosper in the rapidly modernizing world, women would be needed in the workforce, rather than be veiled and secluded, and he introduced measures to facilitate this. In 1953 General Mohammed Daud became the prime minister and also established a series of social reforms, specifically abolishing the purdah, which secluded women from the public. For a short time, during the mid-twentieth century, Kabul was called “the Paris of central Asia,” where, as Elisabeth Bumiller of the New York Times describes in an article from 2009, “there was relative stability and by the 1960s a brief era of modernity and democratic reform. Afghan women not only attended Kabul University, they did so in miniskirts. Visitors—tourists, hippies, Indians, Pakistanis, adventurers—were stunned by the beauty of the city’s gardens and the snowcapped mountains that surround the capital.”

One particularly telling photo from the article, taken by William Borders in 1977, is of two women in Kabul dressed in Western attire and has been referenced as evidence of a time when Afghans lived in a more progressive and freer nation. Yet in that same photo, off to the side and easy to miss, is another woman hidden behind her burqa, her face obscured by the fully opaque veil. Like the miniskirts in Kabul, the reforms and freedoms that Afghans enjoyed during the middle of the past century would not last. The changes implemented by Amaah and Daud were resisted and led to their downfalls. What was once a more tolerant city with a community of several thousand Jews, Kabul now has a just single, unused, dilapidated synagogue and peculiarly only one Jewish Afghan, the synagogue caretaker Zablon Simintov, in a country of approximately 30 million people. As time progressed, Kabul was seriously and repeatedly damaged through a number of conflicts and lost both its tourist revenue and its Parisian moniker.

Today Afghanistan ranks among the least free countries on the planet. In 2009 UNICEF gave it the dubious distinction of being the world’s worst country in which to be born. In Transparency International’s 2010 Corruption Perceptions Index, Afghanistan was ranked 176 out of 178 countries, and only six countries were given a worse score in Foreign Policy’s annual Failed State Index. And while the organization Freedom House accurately notes religious liberty is not as bad now as it was in 2001, when the Taliban were in total control, it declares that overall liberty in Afghanistan is still trending downward, especially because of the parliamentary elections in 2010, which were widely believed to be fraudulent.

The Afghan constitution, adopted in January of 2004 by Afghanistan’s Grand Assembly, was intended to provide for freedom of religion and a greater sense of liberty for its citizens. Article II of the constitution declares that “followers of other religions are free to exercise their faith and perform their religious rites within the limits of the provisions of law.” This seemingly progressive statement almost gives hope that the legal system is indeed on the side of the persecuted. However, the first three articles also set up Afghanistan as an Islamic republic, where “no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.” In addition, no political party can be set up that might be “contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam,” and any member of the Afghan Supreme Court should either have a law degree or be educated “in Islamic jurisprudence.” Article 62 limits the Afghan presidency to Muslims, and article 74 says that any government minister must swear an oath of office swearing to “support the provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.” Perhaps most alarmingly, article 54 prohibits any private child-rearing activities or family “traditions contrary to the principles of sacred religion of Islam.” The constitution of Afghanistan does not even allow for judicial review, which, given the propensity for Islamic jurisprudence among members of the Afghan Supreme Court, it is unlikely that any of these contradictory and intolerant measures would be struck down even if it did.

Afghanistan has approximately 3,000 Sikhs, 400 Baha’is, 100 Hindus, and as many as 8,000 Christians. But one has to wonder how any non-Muslim Afghans, estimated to be just less than 1 percent of the population, are truly “free to exercise their faith and perform their religious rites,” as the national constitution so explicitly states, when they are barred from higher office, from forming any political party in opposition to state Islam, or from carrying out private ceremonies or household customs that may conflict with Islamic teachings. Additionally, Freedom House explains that any non-Muslim proselytizing is strongly discouraged and that “a 2007 court ruling found the minority Baha’i faith to be a form of blasphemy, jeopardizing the legal status of that community.”

It might not come as a surprise that Afghanistan joins countries such as Somalia, Egypt, and Russia on the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) Watch List for countries “which require close monitoring due to the nature and extent of violations of religious freedom engaged in or tolerated by the governments.”

The 2010 International Religious Freedom Report (IRFR)—an annual report produced by the U.S. State Department, mandated by and presented to the U.S. Congress—said that Hindu and Sikh communities in Afghanistan face obstacles when trying to obtain land for cremation and discrimination when applying for public-sector employment. Harassment and intimidation during major celebrations is frequent, and media law prohibits the promotion of religions other than Islam. In another interesting contradiction, according to the IRFR, in legal scenarios in which “the constitution and penal code are silent, including conversion and blasphemy, courts relied on their interpretation of Islamic law; some interpretations of which conflict with the mandate to abide by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which the country has signed.”

These predicaments cause understandable concern for the country’s non-Muslim population. A lack of government response and protection for religious minorities is one of the IRFR’s chief complaints against Hamid Karzai’s administration in Kabul. Yet, despite the isolation and threats facing these communities, it is the religious oppression facing Afghanistan’s Muslims that could be considered even more disturbing. Blasphemy and conversion from another religion are both religious crimes that apply only to the Sunni majority and the Shia minority, and both carry the potential of execution by stoning. The IRFR explains that even though in Afghanistan “the criminal code does not define apostasy as a crime, and the constitution forbids punishment for any crime not defined in the criminal code,” “the penal code states that egregious crimes, including apostasy, would be punished in accordance with Hanafi religious jurisprudence. . . . Converting from Islam to another religion was considered an egregious crime, and therefore, fell under Islamic law.” The report continues, stating that citizens who had “converted from Islam had three days to recant their conversion or be subject to death by stoning, deprivation of all property and possessions, and the invalidation of their marriage.” Afghan Muslim blasphemers can expect very similar treatment, although, fortunately, penalties for these crimes have not been carried out in recent years by either national or local authorities.

When firebrand preacher Terry Jones burned a copy of the Koran earlier this year in Florida, he faced a barrage of condemnation. The backlash in Afghanistan was devastating. Foreign workers at a U.N. compound were killed in a series of violent protests. While the Koran burning may have been deplorable and inexcusable, the actions of Afghan protesters, who murdered innocent U.N. workers, are even worse.

Afghanistan may be a freer country now than it was under the Taliban. Its curiously worded constitution may theoretically allow for freedom of religion throughout the country. But Afghanistan should look to its more tolerant past if it hopes to create a safe, democratic, and prosperous future. The state of religious freedom in Afghanistan for now is deplorable.

Article Author: Martin Surridge

Martin Surridge has a background in teaching English. He is an associate editor of ReligiousLiberty.TV, an independent news Web site. He writes from Calhoun, Georgia.