GR8 PL8 DEB8

November/December 2008

I was young. It was the 1980s. I had a hot, black, complete with pop-up headlights and a vanity plate reading "KTCHME." It was a great car, a great plate. Today if I chose a vanity plate it would probably be a bit more sedate. The question is Would it be sedate enough, and, more important, noncontroversial enough, to be approved by the DMV?

Chances are that Shawn Byrne, a fellow Vermonter, wasn't worried about whether or not his plate was sedate or noncontroversial enough. It was all about love. He offered three choices: "JOHN316," "JN316," and "JN36TN." The first two were rejected on the basis that they violated the state's requirement that vanity plates have no more than two numerals. The third choice was rejected based on the fact that it conflicts with a rule against religious viewpoints on license plates. His choice is, of course, shorthand for a Bible verse: John 3:16, "For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life" (NIV). *

"'The DMV has the right to prohibit religious messages on license plates provided it does not discriminate based on the particular message or viewpoint,' U.S. Magistrate Judge Jerome J. Niedermeier wrote in his 23-page report filed in U.S. district court in Burlington." 1

This, despite Niedermeier's admittance that getting the point of what Byrne's license plate refers to takes some mental gymnastics and that he wasn't sure anyone reading the plate would immediately realize it was referencing a Bible verse. 2

Of course, one could argue that "JN36TN" could also be a reference to someone named John born at 3:16, or a father named John who passed away on 3/16. The point is it could mean any number of things. But because the most obvious reference, in fact the actual reference, is to a verse from the Bible, it's not allowed. End of discussion.

Since this issue has come to my attention I have personally seen the following vanity

plates just driving around my little corner of the state: MRSTIFY (a Viagra salesman?), KGB (the Russians are coming), CALLMOM (a desperate housewife?), and my favorite, HITMAN (oh, now I definitely feel safe). While each of these license plates is more or less offensive to me they also have more than one potential meaning. CALLMOM might be a reminder to reach out to our mothers, a worthy message. Perhaps the letters KGB are the initials in someone's name—Katherine Gloria Burns. MRSTIFY might actually be MRS TIFY, and who am I to denigrate her last name? Although the state of Oregon didn't seem to mind doing just that when they ordered Mike and Shelly Udink to turn in their vanity plates UDINK1, UDINK2, and UDINK3 because their Dutch last name is similar to an offensive word. And HITMAN? Saying hello to a college buddy—HI TMAN? Probably not, but still free speech is supposed to be free speech—others don't have to agree with us, but they must let us speak nonetheless.

The trouble is almost anyone can be offended by almost anything. It all depends on your point of view. "Professor Marybeth Herald, in her Colorado Law Review article 'Licensed to Speak: The Case of Vanity Plates,' " " argues that judges must not allow government officials to regulate offensive vanity plates because offensiveness is in the eye of the beholder and is an almost limitless concept.

"'The First Amendment is an insurance policy against government repression,' Herald writes. 'We pay for it all the time—in large and small ways—by tolerating the racist, the pornographer, and the generally offensive speaker. . . . So if someone wants a plate that says "GOVTSUX," let her have it. Who knows, it might even have been a popular plate among a few of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.' " 4

The debate over license plates centers around two primary types of plates: "vanity" and "specialty" plates. Vanity plates consist of a combination of numbers and letters chosen by individuals to express themselves. The question with vanity plates is How far can the government go in refusing or regulating personal expression, i.e. free speech, on government property (the license plate) in public view? The second type of plates, "specialty plates," are those that organizations can petition for that raise money for their cause and publicize their message. The two most controversial so far have been those involving the anti-abortion message and the Confederate flag.

The Issues Behind the Issue

License plates are owned by the government, but messages on vanity plates are personal and individual; they are clearly not government messages, but reflect the personality or creativity of the car owner. However, that does not mean that courts or legal commentators are agreed on whether or not individuals have the right to say what they want on this form of government property.

"Government officials in license plate cases repeatedly try to advance the so-called 'government-speech defense.' They claim that because specialty and vanity plates are a form of government speech, traditional First Amendment principles do not apply. The government-speech doctrine holds that the government can speak for itself and propound certain viewpoints when it is advancing its own speech." 6

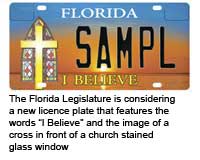

The issue becomes even more clouded in regard to specialty plates, as these are offered by the state and can encompass a plethora of themes. The state of Tennessee, for example, offers more than 90 specialty license plates for Tennessee motorists to choose from. The plates represent colleges and universities, military branches, professional organizations, special interest organizations, and more. Some are more controversial than others. In the state of Florida lawmakers are currently debating whether or not to offer a specialty plate with the design of a Christian cross and stained-glass window with the words "I Believe." If approved Florida would become the first state with a license plate featuring a religious symbol that isn't part of a college logo. You can bet if it's approved, it will be challenged.

The opposing argument, of course, goes that no one is being forced to display any of the specialty plate statements on their vehicle. Participation is completely voluntary and, what's more, you must pay an additional fee for the privilege. Therefore while the individual state governments must approve which messages are chosen to be made available and those messages are supported by the government of that particular state, it's up to the individual who supports that message to purchase the specialty plate, thereby making it the statement of the individual.

Considering the quagmire surrounding this issue it's understandable why many people wonder if the whole vanity plate/specialty plate issue is just a big can of worms the government opened by mistake, and will end up being a lose-lose situation. It's no wonder South Dakota toyed with the idea of doing away with them altogether. But vanity plates have many supporters, so it's not likely that this issue will die down anytime soon.

Meanwhile, vanity plates will continue being requested, denied, and appealed. As for Shawn Byrne, he's not giving up. While he doesn't think they'll be able to change the legislation as they originally hoped, he's confident that in the end he'll get his plate.

"When the state opens up vanity plates to wide-open expression on virtually any subject matter, including what people personally believe as their philosophy and belief system, they can't prohibit Christians or religious people from expressing their point of view on that same subject matter," said Byrne's lawyer, Jeremy Tedesco, of the Arizona-based Alliance Defense Fund. 8

As Hillmer says, " 'Free speech means that I have the right to say on my plates pretty much what I want to.' . . . 'The state should not be in the position where we have to monitor what meets the test of free speech and what does not.' "9

In the end I have to agree with Ken Paulson, of the First Amendment Center, who wrote, "It's a remarkable nation that can tolerate 'ARYAN1' in the interests of protecting 'ROMANS5.' In the end, it all comes down to protecting 'FRESPCH.' "10

C