Is Membership Required for Religious Freedom?

Randy Wright September/October 2011

When Proposition 8 was proposed in California to make marriage between a man and a woman the state's only valid marriage format, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) piled into the political fray in support. They joined Roman Catholics, evangelical Christians, some city governments, and many conservative individuals and groups in a determination to protect traditional marriage as an essential element of American society.

Protection of heterosexual marriage had been a marquee issue for Mormons for decades, and the church's rank and file mobilized in a big way. The Los Angeles Times reported that more than $20 million of the total $40 million raised to pass the proposition was thought to have come from individual Mormon families; and about 45 percent of out-of-state donations came from Mormon-dominated Utah. The level of activism angered supporters of gay marriage.

Voters passed Proposition 8 in November 2008, and the backlash against Mormons was swift. Pro-gay interests launched a retaliatory onslaught that included vandalism of LDS church buildings, vitriolic verbal attacks, intimidation, assaults, and threats to undo the church's tax-exempt status.

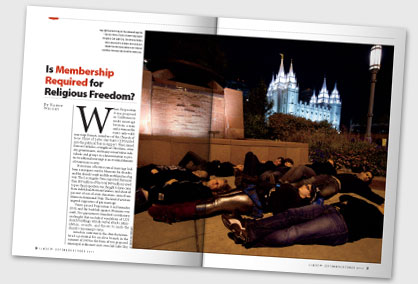

Gay rights activists lay on the sidewalk near the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' temple in Salt Lake City. AP Photo/Jim Urquhart

Awash in controversy, the church encountered a potential for an olive branch in the summer of 2009 in the form of two proposed municipal ordinances in its own Salt Lake City backyard. The ordinances, backed by much of the city council, were favorable to gays. They would ban discrimination in housing and employment on account of sexual orientation. Church support would virtually assure their passage.

A major Salt Lake City property owner with extensive for-profit (and taxable) business operations, the church held off until the last minute because it was concerned that a blanket nondiscrimination law could undermine its First Amendment rights of association by requiring it to bring nonbelievers, or even antagonists, into areas related to its ecclesiastical mission—church offices, for example, or dormitories at church-owned schools. Those fears were eased in negotiations with the city: exemptions were fashioned for churches and educational institutions.

With the new exemptions, discrimination would be allowable "for reasons of personal modesty or privacy or in the furtherance of a religious organization's sincerely held religious beliefs." (Italics supplied.)

The deal tipped the scales. Within hours of the church's endorsement, the two ordinances sailed through the city council on unanimous votes. Homosexuality was still wrong, church leaders said, but that shouldn't get in the way of humane treatment of individuals.

Church spokesman Michael Otterson told the city council: "The issue before you tonight is the right of people to have a roof over their heads and the right to work without being discriminated against. . . . The church supports this ordinance because it is fair and reasonable and does not do violence to the institution of marriage. . . . I represent a church that believes in human dignity, in treating others with respect even when we disagree—in fact, especially when we disagree."

Because the LDS church had never before supported any law expressly speaking to gay rights, the endorsement surprised many and was widely hailed as a seismic shift. The New York Times wrote: "The church's support was seen by gay activists as a thunderclap that would resonate across the state and in the overwhelmingly Mormon legislature." Other headlines across the nation captured the flavor of the national impact: "Utah Leading on Gay Rights," "Landmark Moment," and "Gay Rights Gaining Momentum." Invigorated gay activists immediately launched a campaign aimed at getting the Utah legislature to enact a statewide nondiscrimination law modeled on Salt Lake City's new ordinances, and a number of other Utah cities began crafting their own new rules.

But underneath the news that the Mormons had embraced part of the gay agenda runs a discordant thread. The antidiscrimination ordinances in Salt Lake City, with their exemption for religious organizations only, are out of step with the quintessentially American tradition that religion is a matter of individual conscience. In Salt Lake City the right to associate (or not) with another person on the basis of one's personal religious framework—say, a belief that homosexuality is a grave sin in the eyes of God and a faithful person should not facilitate it—is available only to such corporations as churches, or other formally organized groups, not to individuals.

This sets up a moral and legal clash of potentially epic proportions when viewed against the backdrop of U.S. history and in light of appellate and Supreme Court rulings that appear strongly to support religious privileges on the basis of individual beliefs, not institutional affiliations. The central requirement for First Amendment protection is simply that a person's belief be sincerely held.

The irony is pointed: in Salt Lake City the LDS church as an institution may act on religious grounds in a way that would be illegal for any of its own members. A religious organization is immune from a discrimination charge, while individuals with identical religious beliefs are held to a different standard.

Gayle Ruzicka, Utah president of the Eagle Forum, the conservative political activist group, captured a pivotal point: "We expected the church not to have a problem, because they've been carved out of it," she said of the city ordinances. "The rest of us have not been carved out of it." The ordinances, she said, "discriminate against people who have personal religious beliefs."

Critics say a legal requirement that a landlord must rent property to a homosexual when he sincerely believes that it would facilitate behavior that will bring God's condemnation upon the nation is akin to requiring a Muslim to eat pork, or forcing a Quaker to kill in war. On the other hand, proponents of gay rights argue that allowing an individual the freedom to associate or not with any person as he chooses would undo the whole idea behind nondiscrimination laws. If individual scruples can override generally applicable laws, they say, then the laws have no real force, and discrimination will become pervasive, as with racial discrimination in the South.

Yet religion clearly occupies a special place in American tradition. In her eloquent dissent in a Supreme Court decision invalidating key portions of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA), Justice Sandra Day O'Connor concluded: "The religion clauses of the Constitution represent a profound commitment to religious liberty. Our nation's founders conceived of a republic receptive to voluntary religious expression, not of a secular society in which religious expression is tolerated only when it does not conflict with a generally applicable law" (City of Boerne v. Flores, 1997).

Her dissent arose from the High Court's refusal to apply a balancing test when considering the sacramental use of peyote (Human Resources of Ore. v. Smith, 1990). The test required that when enforcing a law that imposes a substantial burden on religion, the government must show a compelling interest and then resolve that interest by the least restrictive means available.

The "All Families Are Forever" float makes its way down the street during the Pride Parade in Salt Lake City, June, 2010. AP Photo/The Salt Lake City Tribune, Scott Sommerdorf

As nondiscrimination codes favoring homosexuals multiply across the nation, however, it appears that many lawmakers do find a compelling interest when it comes to shielding sexual preference. Whether, and how heavily, those laws might burden religion appears uncertain, especially in light of the vagaries of individual conscience. In the peyote case, Justice Antonin Scalia's majority opinion came down against individual religious choice. "To make an individual's obligation to obey such a law contingent upon the law's coincidence with his religious beliefs, except where the state's interest is 'compelling'—[thereby] permitting him, by virtue of his beliefs, 'to become a law unto himself'—contradicts both constitutional tradition and common sense," Scalia wrote, adding that a private right to ignore generally applicable laws would create a constitutional anomaly that would lead to the evasion of many laws, including those designed to prevent discrimination.

And yet Salt Lake City's ordinances authorize exactly such private evasion—but only for organizations, not individuals. Its ordinances do that in spite of clear precedent that the sincerely held religious beliefs of individuals are entitled to First Amendment protection. The Supreme Court has spoken unambiguously:

"We reject the notion that, to claim the protection of the free exercise clause, one must be responding to the commands of a particular religious organization," a unanimous Court held in a 1989 case (Frazee v. Illinois Department of Employment Security).

In a similar vein, while serving as a U.S. appeals court judge, Sonia Sotomayor, now a Supreme Court justice, wrote that where conscience is concerned, judicial scrutiny "extends only to whether a claimant sincerely holds a particular belief" (Ford v. McGinnis, 2003). She cited precedent that "courts have jettisoned the objective, content-based approach previously employed to define religious belief, in favor of a more subjective definition of religion, which examines an individual's inward attitudes toward a particular belief system" (Patrick v. LeFevre, 1984).

In other words, an individual's personal scheme of things religious—not the scheme dictated by an institution—is covered by the First Amendment. In fact, no institutional association at all is required for the protection of one's sincerely held religious beliefs.

The implications are not lost on gay rights advocates. When presented with the notion of extending to individuals the same religious exemption enjoyed by institutions, Utah state Senator Ben McAdams, a Democrat who advised Salt Lake City's mayor on the ordinances, said doing that would gut the law.

But would it?

Thomas Kleven provides a thorough analysis of freedom of association in "On the Freedom to Associate or Not to Associate With Others" (Tennessee Journal of Law and Policy, (no. 1 [Fall 2004]), in which he shows the variability of circumstances in which associations may be required, or not required, by government. The question turns on a philosophical fulcrum: on one side is the Lockean view that the individual precedes society; on the other the Aristotelian view that human beings are collective creatures and that "society at large has a legitimate interest in preventing and imposing relationships in the name of the common good."

Kleven proposes his own balancing test to determine how to resolve associational conflicts in which one party wants integration and the other does not. At its center is the scope of the marketplace or "community." If there are ample choices available to accommodate the preferences of either party, the claim for forced integration is weaker than if there are few choices, Kleven writes. Where few choices exist, the majority will tend toward perpetual dominance "and thus strengthen the minority claim for being empowered to force an unwanted relationship on the majority."

Kleven's line of reasoning suggests a basic question for Salt Lake City: Would allowing discrimination by individual landlords with religious scruples really result in a shortage of housing for lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender individuals? Or would each instance of religiously motivated exclusion open a business opportunity for numerous other competitors in the marketplace who have no scruples about renting to gays, and who may in fact prefer them as responsible tenants? If the answer is the latter, one might argue that the law should tilt toward the historical right of conscience.

The same test could be applied to a claim of discrimination against gays in employment. In that case, however, the market inventory would likely be substantially smaller than the housing inventory. Given a limited number of jobs in a given field, the balance may tip the other way.

U.S. courts have wrestled for more than a century with the problematic conflicts that can arise between broad societal goals and individual rights, and they've struck a delicate balance in matters of religion—though not always with perfect consistency. Broadly speaking, an emphasis on the protection of individual conscience seems consistent with American history and traditions. Thus one might argue that, as the relative newcomer, sexual orientation should be supported by compelling justifications before it can reasonably outweigh society's long-established respect for individual religious belief, action, and right of association.