No Religious Tests

November/December 2003

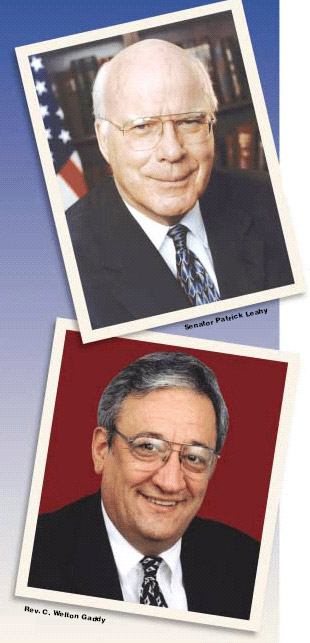

On Tuesday, July 29, 2003, in the Dirksen Senate Office Building, there was a "forum to discuss the recent injection of religion into the judicial nominations process." Senator Patrick Leahy introduced the topic and his personal reasons for participating. After he spoke there were several presentations by various religious leaders and fellow senator Richard Durbin. As a service to our readers LIBERTY presents excerpts of Senator Leahy's comments and the opening presentation by Rev. C. Welton Gaddy, president of the Interfaith Alliance.—Editor.

Partisan political groups have used religious intolerance and bigotry to raise money and to publish and broadcast dishonest ads that falsely accuse Democratic senators of being anti-Catholic. I cannot think of anything in my 29 years in the Senate that has angered me or upset me so much as this. One recent Sunday I emerged from Mass to learn later that one of these advocates had been on C-SPAN at the same time that morning to brand me an anti-Christian bigot. . . . These partisan hate groups rekindle that divisiveness by digging up past intolerances and breathing life into that shameful history, and they do it for short-term political gains. They want to subvert the very constitutional process designed to protect all Americans from prejudice and injustice.

It is saddening, and it's an affront to the Senate as well as to so many, when we see senators sit silent when they are invited to disavow these abuses. These smears are lies, and like all lies they depend on the silence of others to live, and to gain root. It is time for the silence to end. . . . And those senators who join in this kind of a religion smear . . . hurt the whole country. They hurt Christians and non-Christians. They hurt believers and nonbelievers. They hurt all of us, because the Constitution requires judges to apply the law, not their political views, and instead they try to subvert the Constitution. And remember, all of us, no matter what our faith—and I'm proud of mine—are able to practice it, or none if we want, because of the Constitution. All of us ought to understand that the Constitution is there to protect us, and it is the protection of the Constitution that has seen this country evolve into a tolerant country. And those who would try to put it back for short-term political gains subvert the Constitution and damage the country.

The First Amendment encompasses so many different things: the freedom of speech, the freedom to practice any religion you want, or none if you want. We are not a theocracy; we are a democracy. And because we are a democracy, all of us, especially those who may practice a minority religion, get a chance to practice it.

C. WELTON GADDY: Last Wednesday the Senate Judiciary Committee's discussion on William Pryor's nomination to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta deteriorated into a dramatic demonstration of the inappropriate intermingling of religion and politics that raised serious concerns about the constitutionally guaranteed separation of the institutions of religion and government. . . . The debate of that day, though alarming and disturbing, has created a teachable moment in which we will do well to look again at the appropriate role of religion in such a debate. That is why we are here this morning.

Religion plays a vital role in the life of our nation. Many people enter politics motivated by religious convictions regarding the importance of public service. Religious values inform an appropriate patriotism and inspire political action. But a person's religious identity should stand outside the purview of inquiry related to a judicial nominee's suitability for confirmation. The Constitution is clear: there shall be no religious test for public service. . . .

In recent years some religious as well as political leaders have advanced the theory that the authenticity of a person's religion can be determined by that person's support for a specific social-political agenda. So severe has been the application of this approach to defining religious integrity that divergence from an endorsement of any one issue or set of issues can lead to charges of one not being a "good" person of faith.

The relevance of religion to deliberations of the Judiciary Committee should be twofold: one, a concern that every judicial nominee embraces by word and example the religious liberty clause in the Constitution that protects the rich religious pluralism that characterizes this nation and, two, a concern that no candidate for the judiciary embraces an intention of using that position to establish a particular religion or religious doctrine. In other words, the issue is not religion but the Constitution. Religion is a matter of concern only as it relates to support for the Constitution.

Make no mistake about it, there are people in this nation who would use the structures of government to establish their particular religion as the official religion of the nation. There are those who would use the legislative and judicial processes to turn the social-moral agenda of their personal sectarian commitment into the general law of the land. The Senate Judiciary Committee has an obligation to serve as a watchdog that sounds no uncertain warning when such a philosophy seeks endorsement within the judiciary. . . .

The United States is the most religiously pluralistic nation on earth. The Interfaith Alliance speaks regularly in commendation of "one nation—many faiths." For the sake of the stability of this nation, the vitality of religion in this nation, and the integrity of the Constitution, we have to get this matter right. Yes, religion is important. Discussions of religion are not out of place in the Judiciary Committee or any public office. But evaluations of candidates for public office on the basis of religion are wrong, and there should be no question that considerations of candidates who would alter the political landscape of America by using the judiciary to turn sectarian values into public laws should end in rejection.

The crucial line of questioning should revolve around the issue not of the candidate's personal religion but of the candidate's support for this nation's vision of the role of religion. If the door to the judiciary must have a sign posted on it, let the sign read that those who would pursue the development of a nation opposed to religion or committed to a theocracy rather than a democracy need not apply.

In 1960 then presidential candidate John F. Kennedy addressed the specific matter of Catholicism with surgical precision and political wisdom, stating that the issue was not what kind of church he believed in but what kind of America he believed in. John F. Kennedy left no doubt about that belief: "I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute." Kennedy pledged to address issues of conscience out of a focus on the national interest, not out of adherence to the dictates of one religion. He confessed that if at any point a conflict arose between his responsibility to defend the Constitution and the dictates of his religion, he would resign from public office. No less a commitment to religious liberty should be acceptable by any judicial nominee or by members of the Senate Judiciary Committee who recommend for confirmation to the bench persons charged with defending the Constitution.