Quiet Case May Have Far-Reaching Impact

Holly Hollman March/April 2006

Missing were the shouting protestors with placards, the miniature Ten Commandments tablets, and the throng of media representatives. It was almost business as usual the day the Supreme Court heard the term's sole religious liberty case. Unlike the Ten Commandments display cases that received so much media attention last term and flamed the cultural debates on religion, the case of O Centro Espirita Beneficiente Uniao Do Vegetal v. Gonzalez made its way to the Supreme Court rather quietly. At oral argument in November last year, the case drew the attention mostly of the members of the small religious sect whose central sacrament is threatened by the enforcement of federal drug laws against them. While much of the media took a pass on this one, all who are interested in the protection of religious liberty should take note, because the importance of this case may far exceed the particular religious practice at issue.

In broad terms, the case addresses the fundamental question of what the government must do to protect the free exercise of religion. As with many of the Court's religious freedom cases, it also demonstrates how cases dealing with religious minorities and uncommon religious practices often test our country's commitment to fundamental freedoms that others may take for granted. It is in cases arising from religious minorities that courts affirm or deny the principles of the religion clauses that apply to all. Such cases remind us that when religious liberty is denied to anyone, everyone's religious liberty is threatened.

The case began more than six years ago with the federal government's attempt to prohibit a small church from practicing its religion. The church (known as "UDV") has about 150 members in the United States and follows the teachings of a religion native to Brazil. The church's religious practices involve a central sacrament of ingesting a tea, known by its Portuguese name, hoasca, that is ritually prepared from two Brazilian plants. Members of the church believe that hoasca, when used in UDV's religious ceremonies, brings them closer to God. A small amount of the chemical dimethyltryptamine (DMT) results from the preparation of the tea. DMT is on a list of chemicals regulated by the Controlled Substances Act.

The government confiscated the church's plants and records, threatened its members with prosecution, and sought to prevent further importation and use of hoasca. When negotiations failed to resolve the dispute, UDV sued the government under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to stop the government from using the Controlled Substances Act against them. The church presented evidence that the consumption of hoasca has caused no significant adverse health consequences and has not been diverted to illicit use. The government claimed that hoasca posed a health danger to UDV's members and was likely to be diverted to nonreligious use, and its importation from Brazil would cause the United States to violate an international treaty. UDV was successful in the lower court proceedings, and the government appealed to the Supreme Court.

This case marks the first time an RFRA case has reached the Supreme Court since the 1997 City of Boerne case invalidated RFRA's application to state laws. RFRA, which was supported by a broad coalition of religious and civil liberties organizations, including Seventh-day Adventists, Baptists, Catholics, Jews, and Muslims, requires that the federal government have a compelling interest, exercised by the least restrictive means, when it substantially burdens religion. The federal statute, which remains in effect as to federal laws after City of Boerne, is an essential protection for religion in light of the Supreme Court's 1990 decision in Employment Division, Oregon Department of Human Resources v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990), which has been widely criticized for reducing protections under the free exercise clause. Without RFRA, religious practices that are burdened by neutral, generally applicable laws of the federal government would not be protected. When Congress passed RFRA, it did so recognizing that many times general laws incidentally and unintentionally harm religion. RFRA was intended to guard against such harms.

In fact, RFRA was specifically designed to make it hard for government to impinge on the free exercise of religion without a good specific reason. The government's position, however, would allow it to be excused from making the proper statutory showing. As Judge Michael McConnell explained in the case at the Tenth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, "Congress' general conclusion that DMT is dangerous in the abstract does not establish that the government has a compelling interest in prohibiting the consumption of hoasca under the conditions presented in this case."

UDV, and many religious entities that filed briefs on its side, argued forcefully that the government cannot avoid its burden under RFRA by asserting that the drug laws can bear no exemptions. To satisfy the compelling interest test, the government must show a serious harm, based on specific evidence rather than speculation or general statements.

At the Supreme Court, a senior deputy solicitor general, Edwin S. Kneedler, argued the government's case. The questions came quickly, and at least some of the questions from the bench indicated skepticism about the government's sweeping theory. A couple of justices noted exceptions in drug laws for the use of peyote as a sacrament in the Native American Church. Justice Antonin Scalia asserted that such an exception was a "demonstration that you can make an exception without the sky falling in." Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had the same concern and questioned whether permitting an exception for one religious group, but not others, would raise constitutional concerns.

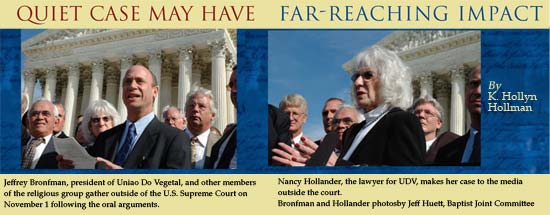

Questions for UDV, represented at oral argument by Albuquerque, New Mexico, attorney Nancy Hollander, however, indicated that the context of the claim in the federal drug law arena and international treaty obligations relating to those laws make this case a challenging one for the Court. Chief Justice John Roberts, hearing his first religious freedom case since his confirmation, asked questions about whether the Court's outcome should be different if UDV expanded or if later hoasca was diverted from its religious use. Others questioned how an exemption for UDV would square with United States treaty obligations.

On February 21, the Court issued a unanimous opinion in favor of UDV. The opinion was written by Chief Justice Roberts in his first religious liberty case. The Court rejected the Government's argument that it had a compelling interest in the uniform application of the Controlled Substances Act that would not allow exceptions to accommodate UDV. That argument was fatally undermined by the longstanding exemption for religious use of peyote by Native Americans. Instead, the Court read RFRA according to its terms and enforced it in a way that bodes well for religious freedom and the continuing vitality of RFRA. Because the case was decided on a preliminary injunction, the case now goes back to district court for additional proceedings.

___________________________

K. Hollyn Hollman is general counsel for the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty in Washington, D.C.

___________________________

Article Author: Holly Hollman

Holly Hollman serves as general counsel and associate executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, where she provides legal analysis on church-state issues that arise before Congress, the courts, and administrative agencies. She is a member of the U.S. Supreme Court, D.C. and Tennessee bars.