The First Freedom

Clifford R. Goldstein March/April 2015Along a wall in the 300,000-square-foot building, where I work—the world headquarters of the Seventh-day Adventist Church—a small [but significant! Ed.] section is dedicated to Liberty magazine. Besides two few framed copies of Liberty, including the first one (1906), and a plaque describing the mission of the publication, 10 photos of 10 men dominate the site. They are, as a sign says, “Liberty Magazine Editors.” A less torqued-out version of my present self sits there quietly between my predecessor, Roland Hegstad (1959-1993) and my successor, Lincoln E. Steed (1999- ). How I, a Jewish kid from Miami Beach, wound up on the wall with all these WASPs is an interesting story, but not one to tell now. The bigger and more important story is that of the Seventh-day Adventist interest in and promotion of religious liberty.

The Theocracy

What’s behind the Adventists’ deep interest in religious freedom, and why do we push it so hard? One reason is simple: we are Seventh-day Adventists, and our adherence to the seventh-day Sabbath has often placed members in difficult situations, either with the law and/or with employers. Thus, religious freedom and the principles behind it have been important to us from the start. The church Web site says: “While we are a rapidly growing denomination around the world, the church often finds itself in the religious minority, and consequently, understands the importance of ensuring that all voices be allowed to speak.”

But even broader principles motivate us as well. These principles stem from the Bible, starting in the Old Testament and reaching their climax in the cross of Christ in the New.

Most people don’t generally think of the Old Testament as any kind of fount for religious freedom principles. Whatever the grandeur of the Israelite theocracy, and in many ways its quite surprising progressiveness (see, for example, the call to cancel debts every seven years),—we generally don’t look to that form of government as an example of religious liberty principles. For instance, the Israelites were told that after conquering a pagan enemy, “you shall destroy their altars, and break down their sacred pillars, and cut down their wooden images, and burn their carved images with fire” (Deuteronomy 7:5, NKJV).1 Those actions, however justified in their immediate context, don’t teach us much in regard to principles of religious freedom, at least in any way that could or should be applied today.

The First Freedom

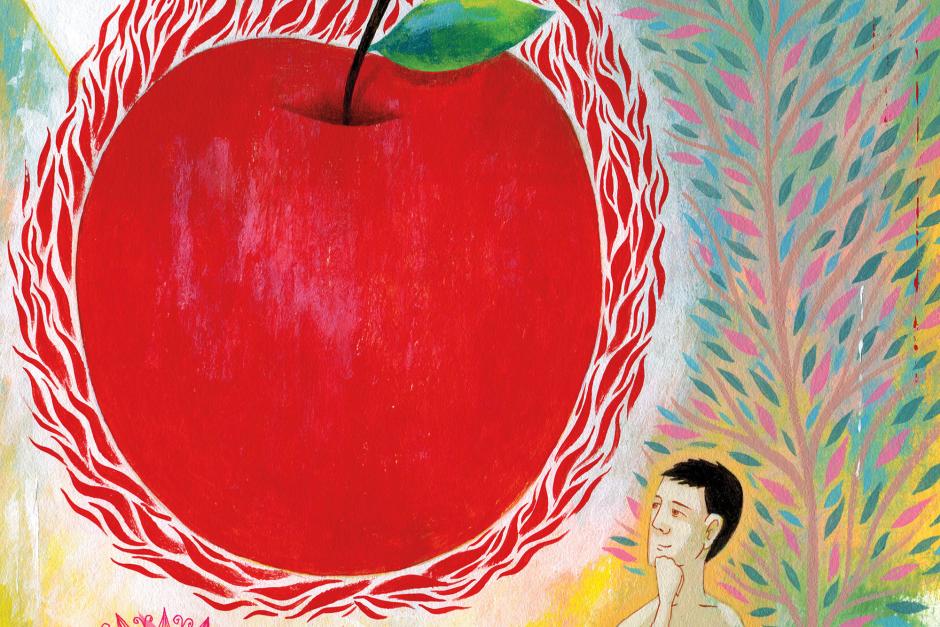

Instead, one needs to go further back in the Old Testament, to Eden itself, for the deepest and broadest manifestations of the religious liberty found in the Hebrew Bible.

According to Genesis, God created the first man, Adam, and then put him in the Garden of Eden. “The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and keep it. And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, ‘You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die,’” (Genesis 2:15-17, ESV).2

Thus, we have here the Lord’s earliest recorded words to Adam. (The command to be “fruitful, and multiply” [Genesis 1:28] apparently came later, because they were spoken to both Adam and Eve, and Eve was not yet created during the narrative of Genesis 2:15-17). These words reveal the reality of the moral freedom that God had woven into the man when He created him of the dust and “breathed into his nostrils the breath of life” (verse 7).

How?

Adam was told, explicitly, that he could eat of any tree he wanted but one, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Why the prohibition if Adam were not capable of violating it? A parent doesn’t tell a child, “Don’t go near Jupiter today,” because there is no possible way that the child could. In contrast, a parent says, “Don’t play with fire,” because the possibility exists for the child to do just that. Thus Adam, in all his original perfection, must have been given the moral capacity to disobey. The prohibition makes no sense otherwise.

The Test

But why was the tree of the “knowledge of good and evil” there to begin with? It works only in the context of Adam, and then Eve, having moral freedom. Here they were, in the midst of a wonderful garden filled with many other trees, all of them freely available for the pair to eat from except this one. The existence of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil was, it seems, a test of loyalty. Would these morally free beings, given so much, obey this one command?

The stark reality of that freedom became apparent in their blatant abuse of it. “When the woman saw that the fruit of the tree was good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom, she took some and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it” (Genesis 3:6, NIV). Perfect beings, created by a perfect God, in a perfect world, nevertheless were capable of disobedience.

And God did not stop them either. He respected their moral freedom. Otherwise the idea of their being free would have been a myth.

Thus here, at the foundation of the world, and of humanity itself, the principles of religious freedom inherent in God’s government were made manifest.

This moral freedom can be seen, in fact, even further back than in Eden. Talking about Lucifer, an angel in heaven, the Bible records God saying to him: “You were the seal of perfection, full of wisdom and perfect in beauty. . . . You were the anointed cherub who covers; I established you; you were on the holy mountain of God; you walked back and forth in the midst of fiery stones. You were perfect in your ways from the day you were created, till iniquity was found in you” (Ezekiel 28:12–15, NKJV).

First, he was a perfect being created by a perfect God, just as Adam and Eve were. Only Lucifer was in a perfect heaven, while Adam and Eve were on a perfect earth. Also, the Hebrew word for “created” in the texts about Lucifer (from the root bara) is the same root used in Genesis 1:1 (“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth”). The verb exists in the Old Testament only in the context of God’s creative activity. Only God can bara.

Nevertheless, what happened to Lucifer, a being created (bara) by God? “Iniquity was found” in him. But how could this be, other than if, as with Adam and Eve in Eden, Lucifer in heaven had moral freedom? This iniquity could not have arisen were not the potential for it already there. And how could that potential have not been there unless, in the perfect environment of heaven, moral freedom existed similar to what existed on earth in Eden?

Thus, as far back as the Word of God takes us, the principles underlying religious freedom are revealed. God created Lucifer, as well as Adam and Eve, with the ability to obey or disobey. Otherwise, they wouldn’t really be free.

Choose Life

No question, God created beings with moral freedom. But the consequences of abusing that freedom are stark. The Bible said that when God created Eden, He put in there two trees: “The tree of life was also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” (Genesis 2:9, NKJV). The tree of life was in contrast to the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and the man was warned that if he ate of the one tree forbidden him, he “would surely die” (verse 17). One tree was life, one death. Adam and Eve chose death.

Why should disobedience lead to something as harsh as death?

Adam and Eve, like any of us, didn’t ask to be born. None of us are here of our own choosing. Life was foisted upon each one of us without our consent. Thus, in the Bible, the real choice facing Adam and Eve, and all of us, is that of life or death. Because we didn’t ask to be here, we are given the option to go back to the eternal nothingness out of which we came, as opposed to the option originally presented to Adam and Eve, and what is offered to each of us now—eternal life. “I call heaven and earth as witnesses today against you, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing; therefore choose life” (Deuteronomy 30:19, NKJV). Or, as John famously says: “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16, NIV).

Eternal life or eternal death? This was the choice given to Adam and Eve. And it is the choice that all of us have as well

The Cross of Christ

This is, of course, where the gospel comes in, and also where the true sacredness and the cost of religious freedom are seen.

In Eden, God told Adam that “in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die” (Genesis 2:17, NKJV). Adam ate, but he did not die that day. Why? Because the moment Adam sinned, the plan of salvation, which was instituted “before the beginning of time” (2 Timothy 1:9, NIV; see also Titus 1:2; Revelation 13:8; Ephesians 1:4, 5), went into effect. The instant that Adam and Eve did the one thing God had said that they should not do, Christ, the Son of God, interceded. He was “the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world” (Revelation 13:8), even though the cross didn’t come until after thousands of years after the creation.

In other words, as soon as there was sin, there was a Savior. Christ knew that He would have to suffer in order to save humanity; yet He became our substitute anyway. As soon as Adam abused the moral freedom given him, the Son of God presented Himself as a sacrifice for the human race, a sacrifice prefigured in the centuries of animal sacrifices offered by the children of Israel. That is, He offered to pay in Himself the death that otherwise would have been ours.

“We all, like sheep, have gone astray, each of us has turned to our own way; and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all” (Isaiah 53:6, NIV).

“God made him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21, NIV ).

“He is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for ours but also for the sins of the whole world” (1 John 2:2, NIV).

“You see, at just the right time, when we were still powerless, Christ died for the ungodly. Very rarely will anyone die for a righteous person, though for a good person someone might possibly dare to die. But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5: 6-8, NIV).

These are just a few of the numerous texts that reveal what happened at the cross. Adam and Eve, in their freedom, chose death over life. Yet the very death that they, and we, deserve as sinners, Christ suffered in our stead, so that we—using the same freedom that Adam and Eve had abused—could make a choice for eternal life.

This is what the gospel teaches.

The Cost of Freedom

But the gospel also teaches something profound about just how sacred and fundamental that moral freedom is. God knew beforehand what would eventually happen with the free beings whom He had created here on earth. He knew that they would sin. He had, then (it would seem), only two choices: not to create humans at all, or not to create them as free moral beings.

He obviously chose neither. Why? Because so basic, so fundamental, is the concept of moral freedom to God’s government that He gave it to us knowing that this freedom would, ultimately, lead Him to the cross. Had God not created humans free, they would not have sinned; and had they not sinned, Jesus would have never died.

Here is, in its most central aspects, the foundation of the Seventh-day Adventist Church’s interest in religious freedom. The idea is as simple as it is profound: if God Himself, even at the cost of the cross, wouldn’t trample on our “religious” freedom, then how dare any human institutions, such as a government? The cross, more than anything in all secular or sacred history, reveals the sanctity of the free moral will that God gave humanity. Thus, the church Web site states: “The Seventh-day Adventist church strongly believes in religious freedom for all people. A person’s conscience, not government, should dictate his or her choice to worship—or not.”

If God respects that choice, we should too.

Of course, it’s one thing to believe in these grand principles. That’s fine, but how are they to be applied in everyday life, as numerous variables and contingencies can and often do bring religious scruples and practices into conflict with the law? Seventh-day Adventists have known these challenges firsthand. Their firm adherence to the seventh-day Sabbath has, at times, put them at odds, not just with the culture but even with the law. In the past, and in some places today, Sunday-closing laws have placed severe economic burdens on Adventists; other times, laws in countries requiring school attendance on Saturday have created great hardship.

But our advocacy of religious freedom, which includes more than 100 years of Liberty magazine, goes way beyond Adventist immediate concerns. We advocate religious freedom because of the principle itself, a principle embodied in the cross of Jesus. And that’s why for six years this Jewish boy, from the shtetl of Miami Beach, and pictured on the wall with all those WASPs, considered it a great privilege to edit Liberty, thus promoting principles that are as old as God Himself.

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.