The Terrorist, the Herdsman, the Emir, and the Bishop

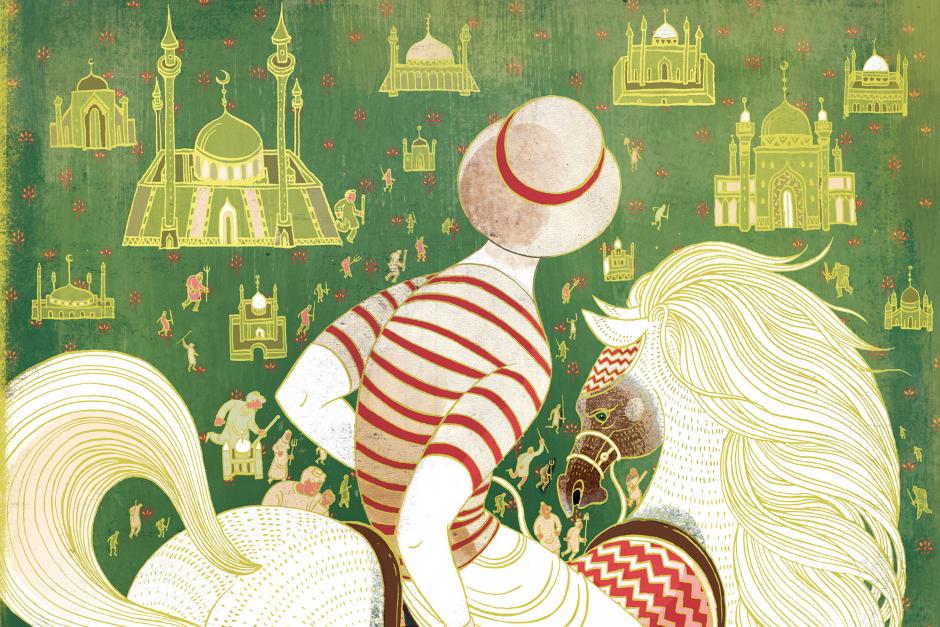

Martin Surridge November/December 2014With the desert sands of the Sahara to their north, the duke and duchess of Gloucester watched as the parade of 3,000 turbaned cavalrymen cantered past in an ancient display of military strength. A brigade of 7,000 chain mail-clad warriors accompanied the riders, as did musketeers, lancers, and archers. A troupe of dancers, musicians, acrobats, and snake charmers followed.

These representatives of English foreign nobility were in Kaduna, Nigeria, witnessing a spectacle imported from India, known as a “durbar,” a ceremonial procession held in honor of a visiting colonial viceroy. The duke and duchess were indeed representing a monarch, but not a Victorian king or an Edwardian queen from during the height of the British Empire. Rather, they had come to Nigeria to represent their niece, Queen Elizabeth II, who ruled as regent during this particular durbar in 1959 and remains on the British throne today.

That such an event occurred only 55 years ago speaks volumes of how much the world has changed, but also of the many difficulties that Nigeria faced during its decolonization process. For the Nigerian people, violence and terror would dominate the next half century, with more lives lost than if their archers and lancers had stepped onto a cold-war battlefield. In order to understand the challenges facing Nigeria today, especially the religious conflict divided by geography that has come to resemble a civil war, the sins of colonial history must not be ignored, just as contemporary acts of terrible violence must not be excused.

The ruling elites of the British Empire were making themselves comfortable in northern Nigeria long before the duke and duchess of Gloucester arrived in Kaduna in 1958. Nigeria’s split between a more arid Muslim north and a tropical non-Muslim south along the tenth parallel north had existed for centuries. Even though one of the motivations for European imperialism was the spread of Christianity—particularly in southern Nigeria, where missionaries would have great success doing so—British officials were much more comfortable in the north, and allowed their partiality to become outright regional favoritism.

In his book Ghosts of Empire: Britain’s Legacies in the Modern World Kwasi Kwarteng explains that one of the causes of Nigeria’s religious conflict today was not Western hostility toward Muslims, but, rather, that Islam was so attractive to the British.

“Islam was something they felt they understood,” Kwarteng writes, “as many of the district commissioners had experience in the Sudan or had served in Asia. British officials appreciated the hierarchy and framework of Islamic society. The ‘savages’ of the south were less well understood. There were, naturally enough, accusations that bias was showed by the British to the north.”1

Kwarteng continues with a quote of the novelist Frederick Forsyth, who once wrote of the British in Nigeria: “‘The English loved the North; the climate is hot and dry as opposed to the steamy and malarial South; life is slow and graceful, if you happen to be an Englishman or an Emir.’ The snobbery and class-consciousness that underpinned so much of British life in the early twentieth century found the idea of feudal rulers familiar and charming.”

Part of that charming familiarity was the game of polo, the sport of kings, played upon horseback. Kwarteng cites a 1980 acknowledgment from the U.K. Foreign Office that the British were “hopelessly biased in favor of the feudal Emirs of the North” and that British officials came to the region with “a romantic passion for Islam and for polo-playing.” Kwarteng writes that it was “in the polo-playing north of the country [where] pageantry, royalty, and invented traditions were combined in the institution of the durbars.”

Decades later, with a burgeoning birth rate and a population of 175 million, Nigeria retains the feudal sense of class-consciousness and medieval attitude toward violence with very little of the supposed colonial charm and pageantry. The present-day partition between a Muslim North and Christian South is partly a legacy of British imperialism—a result of Christian missionaries introducing a new religion into the non-Islamic south and colonial officers strengthening the arid northern regions. Today, according to the U.S. State Department’s “2013 Report on International Religious Freedom,” with approximately 10 percent of the population adhering to indigenous religious beliefs, Nigeria is approximately 50 percent Muslim and 40 percent Christian, making it the largest country split so evenly between the world’s two major religions. Unsurprisingly this has resulted in escalated sectarianism, and in the Middle Belt in particular, the central region of Nigeria where the two religions interact so disastrously, the growth of Christianity is especially dramatic. In her analysis of the Nigerian religious conflict, Eliza Griswold, author of The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches From the Fault Line Between Christianity and Islam, describes how “high birth rates and aggressive evangelization over the past century have increased the number of [Christians] from 176,000 to nearly 50 million.”2 A large number of these worshippers belong to Pentecostal denominations, which has added another level of complexity to the distrust. According to Griswold, for Muslims in Nigeria “who find Christianity’s explosive growth threatening, the Pentecostal language of being saved by the Holy Spirit is especially difficult to fathom. The Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—smacks of polytheism, and the idea that God could father a son is blasphemy.” If deeply held theological differences were not incendiary enough, there are the added financial problems in Nigeria that could cripple even the most sanguine society.

Even though some experts cite Nigeria as one of Africa’s great economic success stories with a giant national oil industry, “more than half of Nigerians live on less than one dollar a day, and four out of ten are unemployed. There are more than sixty million jobless Nigerian youth, a ready army free to man the front lines in any religious conflict.”3 Regardless of the level of poverty and unemployment, a growing number of Nigerians must choose a side to safeguard what little they have.

Griswold writes that “in many regions, the state offers no electricity, water, or education. Instead, for access to everything from schooling to power lines, many Nigerians turn to religion. Being a Christian or a Muslim, belonging to the local church or mosque, and voting along religious lines has become the way to safeguard seemingly secular rights.” For the Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, agnostics, atheists, and others left unaffiliated, Nigeria has become a dangerous place.

The case of Mubarak Bala, a chemical engineering graduate from the predominantly Muslim area of Kano in the north, became an international news story in July after his family admitted him into psychiatric care against his will for stating his atheism. According to the BBC, Bala received death threats for his nonbelief, and the hospital held him for 18 days before international organizations and a doctors’ strike resulted in the hospital discharging him.4 News of his release broke only after he was in a secure location.

Kano is one of several northern states in which state governments fund and support sharia law enforcement groups, albeit “inconsistently and sporadically.”5 Kano in particular attracted the observation of the U.S. State Department and their “2013 Report on International Religious Freedom”: women and men are urged to remain separate when riding public transport, male taxi drivers are reminded not to wear short pants, and in Kano City hundreds of thousands of cigarette packets and bottles of beer were publicly destroyed.6 This system of sharia law in Nigeria’s north includes government-funded sharia courts, which some non-Muslims worry amounts “to the adoption of Islam as a state religion, while the state governments maintained no person was compelled to use the sharia courts, citing the availability of a parallel common law courts system.”7 Conversely, in the south of the country, in the coastal Nigerian metropolis of Lagos, a nonsharia court heard the case of an 11-year-old Muslim girl in the Lagos public school system, caned by her principal in February for wearing her hijab outside of Islamic studies class.

The public school system in Lagos is a direct descendant of the educational system put in place by colonial authorities, whose presence in the country inspired some of the first Muslim uprisings in the region, which had shifted their focus from corrupt local kings and rulers to invading colonists. As the British and other “Christian colonial powers arrived in Africa, these holy wars morphed into battles against the infidel West. These jihads, while largely forgotten, represent some of the earliest and bloodiest confrontations of Islam with the West; they drove colonial policy toward Muslims not only in Africa but worldwide. They also laid the groundwork for Islam’s opposition to the modern West.”8 Although much of the civil strife in Nigeria is a product of the colonial era, the specific split between north and south in Nigeria is a consequence of climate and tropical disease as much as it is foreign intervention.

In 1802 followers of Uthman dan Fodio, an ethnic Fulani herder and Islamic religious teacher, joined their leader in launching a campaign to conquer “a large swath of West Africa as their own Islamic empire.” However, as they traveled deeper south, their surroundings changed dramatically: “When they neared the tenth parallel, the desert air moistened and the ground grew wetter. Here the notorious tsetse fly belt began, and sleeping sickness killed off the jihadis’ horses and camels, effectively halting their religion’s southward advance.”9 The prevalence of malaria was a strong reason British colonial authorities preferred to spend time among Muslims above the tenth parallel north, the circle of latitude 10 degrees or 700 miles north of the equator.

Today the religions remain divided by latitude and intermingle in the Middle Belt. Griswold states grimly that “since 2001, Nigeria’s Middle Belt has been torn apart by violence between Christians and Muslims; tens of thousands of people have been killed in religious skirmishes. . . . Yet these small street fights, infused with deeper hatred, have often given way to massacres in churches, hospitals, and mosques.”10 These conflicts have become charged with the language of holy war, leading one Christian writer to refer to Muslims in Nigeria as “cockroaches” in need of extermination, which Griswold claims is a “deliberate reminder of the 1994 Rwandan genocide.”

For more than a decade the world has watched with equal parts apathy and pity as Nigeria proceeded to tear itself apart. For the Western world and the former European colonial powers in particular, most African conflicts fail to generate significant overseas concern, despite their colonial origins. Before independence, the sport of polo contributed to colonial favoritism in the north and played a part in preventing national cohesion so many years ago. In the twenty-first century a different sport threatens to exacerbate the conflict and deepen the religious divide.

For Nigerians, just as for so many other people around the world, the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil was a source of national pride, a unifying and patriotic rallying cry for their country. The Nigerian national soccer team, the Super Eagles, had won the 2013 African Cup of Nations and was heading into the global tournament in South America with high hopes. Just as in Seattle, London, Barcelona, and Buenos Aires, crowds gathered in viewing centers in Nigerian cities like Damaturu to watch one of the world’s most popular sporting events unfold. On the night of Tuesday, June 17, 2014, however, few in Damaturu were able to enjoy the televised soccer match between Brazil and Mexico, beamed in by satellite from thousands of miles away.

According to a report by France 24’s Nina Hubinet, a deadly explosion, caused by a bomb hidden in a tricycle taxi, ripped through the crowd, killing 14 and injuring 26 others. Just two weeks earlier another bomb had exploded in a northeastern Nigerian soccer stadium, where it killed 40 attendees.11 The central city of Jos suffered a similar viewing center bombing in May. Even though soccer is a favorite sport across the Middle East and the greater Islamic world, northern Nigeria included, to many extremists, the global game reeks of Western capitalism and unwanted cultural influence.

Local as well as international media placed the blame for the attack in Damaturu on the now-infamous Islamic terrorist organization Boko Haram. Led by the disturbingly charismatic Abubakar Shekau, the extremist group shocked the world in April when it abducted more than 200 girls in Borno state in the far northeast of Nigeria. The kidnappings ignited an international outcry, spawning intense media coverage, strong attention on social media, and the famous Bring Back Our Girls movement. While more than 60 of the 200 kidnapped girls managed to escape, the fate of the remaining victims is still unknown. Nigerian citizens took to the streets in protest of government ineptitude at combating Boko Haram, whose atrocities in 2013 alone included the killing of more than 1,000 people through targeting “a wide array of civilians and sites, including Christian and Muslim religious leaders, churches, and mosques, using assault rifles, bombs, improvised explosive devices, suicide car bombs, and suicide vests.”12

The U.S. State Department acknowledges that Boko Haram has apprehended numerous apostates and “attempted to force them to renounce Christianity, killing those who did not convert on the spot. One Christian group reported suspected Boko Haram fighters had attacked a majority Christian town near Gwoza, Borno State, on 11 separate occasions, attempting to force residents to convert or flee.”13

Boko Haram have also targeted Muslims “engaging in activities they perceived as un-Islamic.” In January of 2013 “gunmen reportedly killed 18 hunters selling nonhalal meat at a market in Damboa, near the Borno State capital of Maiduguri. Also in January, gunmen reportedly killed five men gambling by the side of the road in Kano State.”14 The Islamist militants have escalated their rampage in the summer of 2014 with brazen attacks including the kidnapping of the vice prime minister’s wife in Cameroon, where Boko Haram-inspired fighters also killed 10 villagers in a remote village.

In May, militants killed more than 25 people in a northeastern Nigerian village of Chikongudo, near Gamboru Ngala, a town where suspected members of Boko Haram killed more than 300 residents earlier that month. A state of emergency has existed in the northeastern part of the country for more than a year as the death toll continues to rise and Nigerian soldiers fight what looks to be a long and bloody war for many years to come.

It has been widely reported that the eventual goal of Boko Haram is to establish an Islamic state in Nigeria, an aim that bears strong regional and historical precedent. When malaria halted the advancing camels and horses of Uthman dan Fodio and his followers at the tenth parallel two centuries ago, the political objectives were remarkably similar. However, Boko Haram would do well to study Nigerian history. Although it is true that dan Fodio embarked on a jihad to purify Islam and to conquer the region through force of arms, the former herdsman also did so in order to promote the education of women.15 Given the recent Islamist attacks on female students throughout the greater Middle East, this might come as something of a surprise. The very name of Boko Haram translates roughly as “Western education is forbidden,” and the terrorist organization’s kidnapping of Nigerian schoolgirls demonstrates their consideration of the education of women as inherently Western. Vladimir Duthiers, Faith Karimi, and Greg Botelho reported that Boko Haram vehemently “opposes the education of women. Under its version of Sharia law, women should be at home raising children and looking after their husbands, not at school learning to read and write,”16 a message sharply contradicting the teachings of dan Fodio, one of Nigeria’s leading Muslim figures of the nineteenth century.

In contemporary Nigeria heroes of Islam can still be found, but they are not on the battlefield and do not call for violent jihad.

When Eliza Griswold visited Nigeria and reported on her journey in The Tenth Parallel, she wrote of a visit she paid to a local Muslim king called the Emir of Wase. Tired of the violence between Christians and Muslims, the emir and the local Catholic bishop had collaborated in creating a small yellow pamphlet that contained a list of complementary teachings of Islam and Christianity to inspire harmony and interfaith cooperation. Pointing to similar verses in both the Bible and the Koran, the emir explained his findings with the peaceful desires of a man who had seen enough death to last several lifetimes. The author recalled that the king had “highlighted the Quran’s universal messages of coexistence for all of humankind, many of which were revealed to Muhammad early on in his life as God’s messenger,” as well as to Jesus during His ministry in Jerusalem and Galilee. “[He] made the point,” Griswold continued, “that if both of these men, beaten and bloodied—the incarnations of their respective faiths—asked God to forgive their aggressors, then who were today’s leaders to advocate holy war?”

The Emir of Wase explained to his guest that Islam and Christianity were “two religions that were deeply linked,” “but leaders did not know of, or else had forgotten, their common bonds.” “These verses command believers to live together peacefully.” “We know that Jesus taught that if someone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to the left. We know that Muhammad was sacked from his village and stoned at Ta’if, but he quietly left for Medina.”17

The world may never know whether the local population of Wase ever transformed their thinking because of picking up the little yellow pamphlet produced by the emir and the bishop. Perhaps its success will be judged on how few of the Nigerian people reach for their rifle instead.

1 Kwasi Kwarteng, Ghosts of Empire: Britain’s Legacies in the Modern World (New York: PublicAffairs, 2011).

2 Eliza Griswold, The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches From the Fault Line Between Christianity and Islam (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2010), p. 19.

3 Ibid.

4 BBC News, “Nigeria Atheist Bala Freed From Kano Psychiatric Hospital,” July 4, 2014.

5 U.S. Department of State, “2013 Report on International Religious Freedom.”

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Griswold, p. 21.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid., p. 18.

11 Nina Hubinet, “Africa—Boko Haram’s War on the World Cup,” France 24, June 20, 2014.

12 U.S. Department of State, “2013 Report on International Religious Freedom.”

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Griswold.

16 Vladimir Duthiers, Faith Karimi, and Greg Botelho, “Boko Haram: Why Terror Group Kidnaps Schoolgirls, and What Happens Next,” Cable News Network, May 2, 2014.

17 Griswold, pp. 22, 23.

Article Author: Martin Surridge

Martin Surridge has a background in teaching English. He is an associate editor of ReligiousLiberty.TV, an independent news Web site. He writes from Calhoun, Georgia.