The Word Unchained

Getahn Ward March/April 2008

The outcry led to a change in the policy. It was a policy under which almost 330,000 books such as Rabbi Harold Kushner's classic When Bad Things Happen to Good People and Christian pastor Rick Warren's best seller The Purpose Driven Life were removed under a push officials said was aimed at shielding inmates from materials that could be used to radicalize them.

But should the government be deciding what are appropriate religious materials? That was among the questions raised in a lawsuit brought against the Federal Bureau of Prisons by an Orthodox Jewish and a Christian inmate housed at a federal prison in Otisville, New York.

The library revision had its roots in a 2004 Justice Department Inspector General report entitled A Review of the Federal Bureau of Prisons' Selection of Muslim Religious Services Providers. It cited deficiencies in how the bureau selected and supervised Muslim chaplains and said several visited prisons lacked an inventory of books available to inmates. It noted that none of the collections had been rescreened since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

"We agree with trying to keep out of libraries radical books that advocate violence," said Pat Nolan, a vice president of Prison Fellowship Ministries of Lansdowne, Virginia, an outreach to prisoners, former prisoners, and their families. "The problem was they threw the baby out with the bathwater. They took out a lot of good books along with any that might have been bad."

Nolan interpreted the bureau's policy modification as moving from the position that no book would be placed in the religious libraries of prisons unless approved by the government to one where books would be eligible as long as they are religious in nature; don't jeopardize safety, security, or order; don't facilitate criminal activity; and can't be used to radicalize or incite inmates to violence.

For materials that don't meet the criteria, chaplains will be able to submit a form stating the reasons for their objection to a central office to be reviewed separately, Nolan added.

Mike Truman, a bureau spokesman, said books other than those considered inappropriate will remain on shelves of libraries until an inventory of materials is completed in early 2008. "The BOP [Bureau of Prisons] has the authority to regulate materials entering our institutions and has the responsibility to ensure the ongoing safety and security of each facility," he said, suggesting that books that could be used to radicalize or incite inmates to violence will still be purged. Officials don't see the library revisions as a violation of constitutional rights, Truman said.

Although the Bureau has some funds for the purchase of religious books, the majority of the books and materials available to inmates in chap_els are donated by religious ministries and others. Inmates also can individually receive books directly shipped from approved vendors such as mail order companies, bookstores, and publishers, or donated by various ministries. These can be books inmates ordered or that were purchased by family members and friends.

Only chapel and religious libraries—not leisure libraries in the federal prisons—were targeted under the bureau's so-called Standardized Chapel Library Project. Before removing the titles not on the newly created approved list, the Bureau said it consulted with experts representing many religions in its inmate population to certify the content of about 150 print, 150 audio, and 150 video holdings for inclusion on an initial standardized list of religious books and videos for each religious group. The plan was to continue to add to the more than 3,000 entries as materials were reviewed and approved, Truman said, adding that availability of basic worship resources like Bibles and Korans was never affected. "It should also be pointed out that no books, videos, or audiotapes were destroyed," he said.

However, Michele Deitch, who teaches criminal justice policy at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas in Austin, was shocked that bureau officials considered their action constitutional. "There's always been an effort to take away controversial things, but religious materials had always been given a very different status."

Because of the volume of books involved, the bureau likely took the easier path of creating a smaller list of preapproved books to avoid having individually to decide which titles to screen and toss out, says Douglas Laycock, a University of Michigan Law School professor and expert on religious liberty and the separation of church and state. "The constitutional issue is whether that's a far more restrictive method than necessary and where the government gets authority to choose and approve religious books for different religions."

Lane Dilg, a staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union's program on Freedom of Religion and Beliefs in Washington, D.C., was concerned that some minority religions might have been excluded from the bureau's initial list of approved books and materials. "The government is no more entitled to impose religious orthodoxy in prison than it is outside of it," she said. "An approved book policy couldn't possibly meet the needs of all inmates."

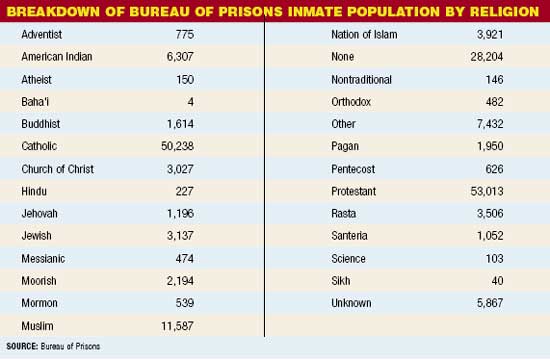

Out of the nearly 190,000 federal prison inmates, almost 60 percent identified themselves as being of a faith linked to Christianity. About 8 percent, 15,508, identified themselves as either Muslims or members of the Nation of Islam, 15 percent didn't list a religion or said they were atheists, and the remaining 15 percent represented a range of other faiths including beliefs associated with American Indians and Buddhism, Hinduism, and Judaism.

The bureau listed nearly 150 books and other Islamic materials on an initial list of approved books and materials. But the lawsuit filed by the two inmates at the Federal Prison Camp in Otisville, New York, suggested that before all books were later returned, the Muslim portion of the chapel library had all but disappeared, with only the Koran and two other titles left.

Moses Silverman, the New York-based lawyer representing Moshe Milstein (who is now at a halfway house) and John J. Okon, said his clients won because the books were returned, but whether they will continue to pursue the case would depend on what happens next.

Over the years, inmates have brought many lawsuits that argue against denial of their First Amendment rights and violation by prison officials of laws, including the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA). The laws protect the religious exercise of an institutionalized person and set a stricter standard of scrutiny for actions that limit prisoner religious expressions, but law professor Laycock says provisions guaranteeing religious literature in prisons aren't as clear as they should be.

That may partly explain the varying directions in which courts have ruled on related cases.

In an opinion issued in 2003, New York federal judge Naomi Reice Buchwald ruled that Intelligent Tarref Allah, formerly Rashaad Marria, was entitled to copies of the central text, The 120 Degrees, and certain other materials associated with the Nation of Gods and Earths, also known as the Five Percenters. She concluded that the Nation was a religion and not solely a gang, as it had been classified by New York corrections officials. She later agreed with prison officials that allowing one-on-one meetings with outside volunteers could pose a security threat because of prison staffing issues and members' past history of violence.

Erik Kriss, a spokesman for New York's Department of Correctional Services, said that since 9/11 the agency has been more vigilant in monitoring inmates, including whenever they gather, for security reasons and to keep its prisons safe. "We respect the First Amendment, but we have people inside the prison system who have committed crimes and caused violence," Kriss said. "We respect anybody's rights to practice as long as they're not using it to plot."

In another more recent ruling, a Michigan federal district judge adopted recommendations of a federal magistrate, holding that prison officials had qualified immunity from damage claims in connection with their seizure from the inmate plaintiff of religious materials from the Nation of Gods and Earths. However, the judge also concluded that the plaintiff was permitted to proceed with his claim for an injunction seeking removal of the "security threat" designation given the Nation and challenging the taking of his religious literature.

And last year a California federal court concluded in a case brought by Jesus Christ Prison Ministry and three state inmates that prisoners' rights were violated by the policy of a prison facility that prohibited unapproved vendors from sending free softbound Christian literature, compact discs, and tapes to prisoners who had requested those materials.

Bill Sessa, a spokesman for California's Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, said that the agency corrected the problem by creating a master list of vendors. Instead of each prison having its own list, approved vendors can sell books to any inmate in any prison.

"There's no censorship of which religions can have materials in prison, only where books are coming from," he said. Inmates' backgrounds, gang ties, and divergent views are bigger influences on attitudes and propensity for violence than what they read in chapels, he said.

However, some civil libertarians and prisoner rights advocates take issue with restrictions on which publishers are allowed directly to sell materials to prison inmates. Gary Friedman, spokesman for the American Correctional Chaplains Association, said the Bureau of Prisons previously had a list of nine banned publishers, which included two Muslim publishers and mostly Christian distributors of materials that promote hate—such as White supremacist ideologies. It has now modified that policy to look at publications on an item-by-item basis, he said.

Friedman, chairman of Jewish Prisoner Services International, which provides religious services and materials to Jews in prison and their families, says that a lot of people in the Muslim community are apprehensive about participating in prison religious programs for fear of being suspected of radicalizing inmates.

"The Muslim chaplains I've worked with are phenomenal people who do an incredible job, don't teach terrorism or hatred, and contribute greatly to the orderly operation of prisons," says Friedman, also a Washington state chaplain. "In rural areas, where most prisons are located, it's always been hard enough to get minority clergy and volunteers. The current anti-Islamic climate in the U.S. is making it even more difficult for the Muslim community."

Mahdee Abu-Abdillah of Nashville, Tennessee, a Muslim handling outreach to area prisons, said he once heard about security concerns regarding hardback books but hasn't had problems getting educational materials to inmates. "I'm all for keeping that type of stuff out of the prisons and even the country in general," Abu-Abdillah said about books by extremists.

Ron Turner, director of religious services with the Tennessee Department of Corrections, said prisons have always screened for materials that could threaten safety and security, but legitimate religious materials have always been permitted and protected under the law.

"To do a wholesale removal of religious materials from the libraries of prisons appears to me to be a clear violation of RLUIPA," he said about the law. "One reason the BOP pulled back from their position, I think, is that they realized that they had gone too far—that in removing so much religious materials from libraries, they were probably violating RLUIPA."

For now, civil libertarians, religious groups, and prisoner rights advocates see the change in how the bureau is implementing the library revision plan as a victory. "I'd say this is what our civic teachers taught us that government should work like," said Prison Fellowship's Nolan. "We were able to protest, they listened to our concerns, and. . . changed their policy."

Getahn Ward is a Nashville, Tennessee-based freelance writer who focuses on business and religion issues.