A Lament for Christianity’s Political Turn

Ed Guthero March/April 2024Tim Alberta’s new book takes an inside look at the struggle for the soul of American evangelicalism.

Picture this. A pastor finishes his sermon, offers a closing benediction, then closes his Bible. He has just preached a moving homily on the Beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew—a cornerstone teaching of Christianity. He walks to the church lobby and begins shaking hands with his parishioners.

“Where did you get those liberal talking points?” someone abruptly challenges him.

“I’m literally quoting Jesus Christ,” the startled pastor replies.

“Yes, but that doesn’t work anymore. That’s weak.”

In his book Losing Our Religion: An Altar Call for Evangelical America leading evangelical writer and theologian Russel Moore recounts how many discouraged pastors have described similar scenarios happening within their own congregations.

How did we get to the point where the teachings of Jesus Himself are considered too “woke” for some Christians?

Moore is just one of many evangelicals interviewed by Tim Alberta during his extensive cross-country quest to take the temperature of this influential movement. Alberta is a staff writer for The Atlantic, an award-winning journalist, and best-selling author. He is also a Christian, the son of a pastor. He grew up in the church and cherishes the restorative message of the Gospels, but he is also a journalist, intent on seeking facts.

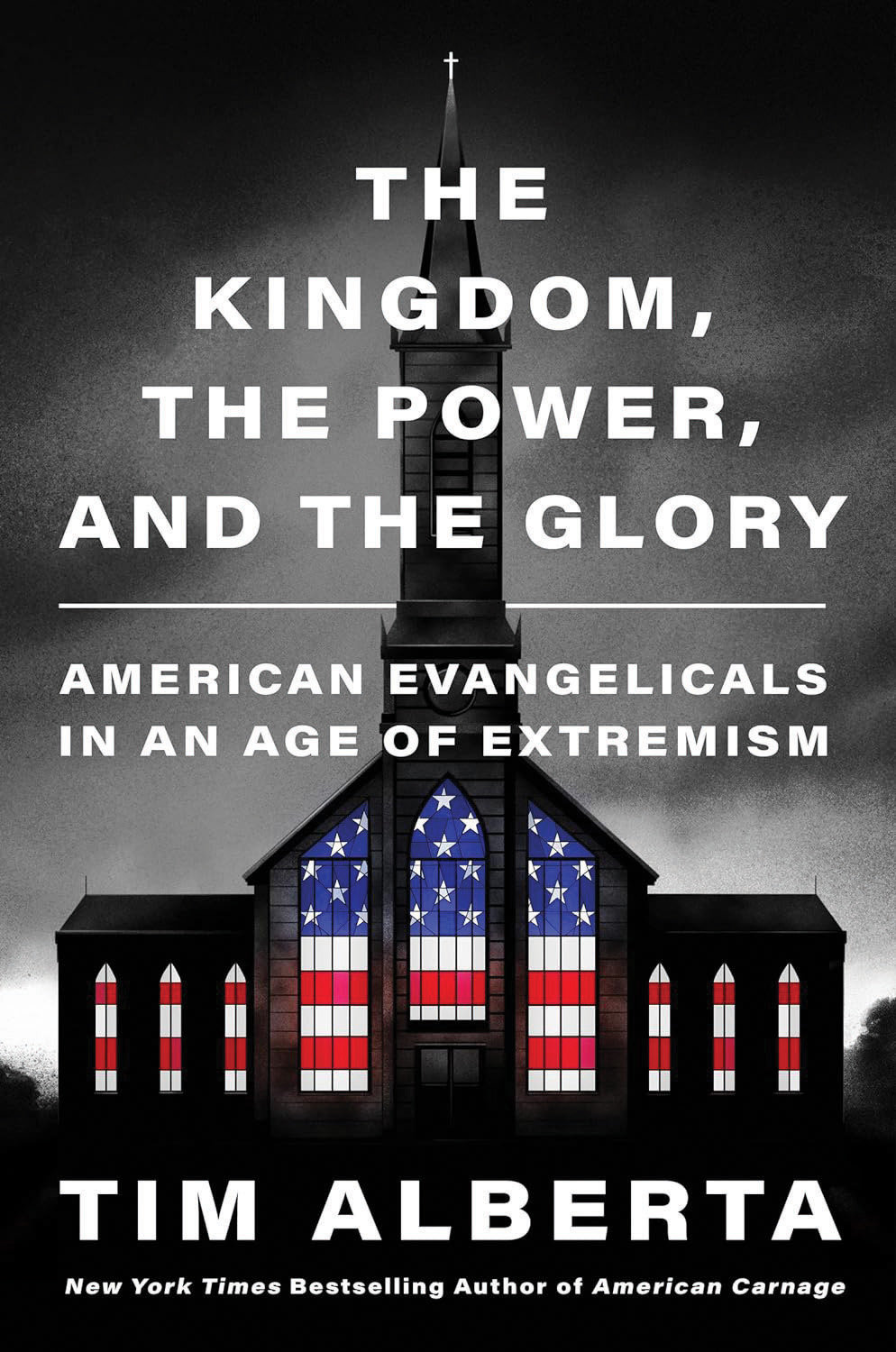

Alberta’s new book The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory is a riveting portrait of faith under siege, broken trust, money, and manipulation for power and political gain, as well as hope, courage in the face of a storm, and the ultimate bottom-line question: What does it really mean to be an evangelical in America today?

The word “evangelical”—from the Greek euangélion, meaning “good news,” or “gospel”—was once a respected term of personal faith in Christ. Yet now it seems to primarily describe a political identity.

A Vulnerable Enemy

Alberta traces the genesis of his current book to the aftermath of the death of his beloved minister father. It was July 29, 2019. Richard Alberta, the longtime pastor of Cornerstone Church in Brighton, Michigan, died suddenly of a heart attack. He had seen his congregation grow from a few hundred to a few thousand members, and now he was gone.

Numbed, Alberta returned to the church he was raised in, this time to honor his father and give the eulogy. At the time, he was unaware that conservative talk radio host Rush Limbaugh had recently gone on air to criticize Alberta’s writing about then-president Donald Trump.

On the worst day of his life, at his dad’s funeral, in the church of his youth, while standing in the receiving line with his family, Alberta found himself confronted and derided.

“Here, in our house of worship, people were taunting me about politics as I tried to mourn my father. . . . All this while my dad was in a box a hundred feet away,” Alberta recalled. “They didn’t see a hurting son; they saw a vulnerable enemy.”

Jesus: Culture War Mascot?

Alberta realized that something had gone very much awry within the evangelical world. And so for much of the next four years he immersed himself in evangelical culture, traveling the country, visiting “half-empty sanctuaries and standing-room-only auditoriums,” talking with megachurch preachers, small town ministers, religious political operatives, faith leaders and administrators, and everyday church members.

Alberta observed traveling road shows pushing extreme political agendas with a bizarre menagerie of religion, election denial, QAnon material, and a myriad of merchandizing, including “Jesus Is a Bad A**” T-shirts. The scenes echoed the disturbing images of the January 6, 2021, insurrection when traditional Christian symbols were visible along with QAnon symbols sewn on American flags, and banners proclaiming “Jesus is my Savior, Trump is my president.”

The Paradox of Gaining the World

Alberta writes with frankness, detail, and clarity. The reader can feel the author’s heart breaking at what he finds. This is not the church of his father. This is something different, dangerous, and weaponized for political gain. Something that assumes that “the best way to preserve Christian virtue is to first set Christian virtues aside.”

“If Jesus warned us that what comes out of our mouths reveals what resides in our hearts, how can we shrug off lies and hate speech as mere political rhetoric?” Alberta asks. “Why is there an exception for politics?”

In reading the book, I was particularly struck with the candor of those Alberta interviewed— prominent figures in the evangelical world who promote the alliance of faith and political power. In their conversations with Alberta, some seem to pause for self-reflection, conflicted about their involvement. Have they gone too far? Others seem so invested that they won’t second-guess themselves.

Since Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority of the late 1970s, evangelicals have flirted with using religion to gain cultural and political power. Today, though, a new form of religion has emerged from a troubling mix of Christian nationalism and the cult of personality. Riding a wave of misinformation, this new faith is ripping at the soul and identity of evangelicalism. To many of those looking on, “evangelical”—once a statement of loyalty to Jesus Christ— has become synonymous with right-wing political extremism. This new religion has damaged the witness of the Christian church in America, obscuring the gospel of grace and Jesus’ message of personal restoration. As Alberta observes: “The forces of political identity and nationalist idolatry, long latent, now fully unleashed in the form of Trumpism, were destroying the Evangelical Church. . . . Churches were not a bride to be loved, but a battlefield to be conquered.”

Political power as a substitute religion falls short. “The problem within evangelicalism,” one pastor confides to Alberta, is that people “worship America.” This idolatry is fueled by the belief, in Alberta’s words, that “America is a kingdom ordained by God and must be fought for as though salvation itself hangs in the balance . . . as if God himself would be defeated if an election is lost.” This exclusive focus on America is ironic, given the universality of Christ’s message: the gospel of the cross and resurrection is for all humanity, not just America.

Finding Our Focus

Are megachurches, dominating the culture, and winning elections really the endgame for the Carpenter from Nazareth?

“We in the United States have such an inadequate view of what a Christian is called to be,” one concerned Christian tells Alberta. “The Bible tells us that we are broken beyond repair—all of us—and that Christ came to heal us. Churches are supposed to be hospitals for the sick. And once we’re healed, we’re supposed to be helping others get healthy too.”

Rachel Denhollander, well-known former gymnast and now a lawyer, was one of the prominent evangelicals interviewed by Alberta. “Define your identity,” she told him. “When you lose sight of your identity, it’s easy to lust after power, and to justify the moral compromises necessary to achieve it.”

It is a powerful, sobering statement, one that represents the bottom-line question facing evangelicalism: Which identity will it ultimately choose?

The good news is that a crisis can sometimes lead to self-reflection, forcing us to pause for a reality check. It can lead us to reconsider what Jesus and His teachings are really all about. What we are about.

Alberta’s book introduces us to pastors and congregations across America shattered by the storm of Christian nationalism and extremism that is raging through faith communities. Many pastors have seen hundreds of their parishioners vacate pews, moving on to other groups that fully embrace a gospel of political power. Yet there are also evangelicals who have decided that their identity is in Christ, regardless of discouragement, harassment, or threats. Alberta tells their stories, too, and the hope they embody.

As I was writing this review, a bizarre new political video ad flashed across my computer screen. I paused in disbelief. In solemn, messianic tones, a narrator calls candidate Trump “a shepherd to mankind.” The tagline—“So God Made Trump”—repeats throughout. The religious flavor of this promotion is shamelessly directed toward people of faith. The political manipulation is transparent. Just a few years ago, could such a blatant use of religion for political gain have even been contemplated?

It is a powerful demonstration of why Alberta’s compelling new book is a must-read, both for evangelical Christians caught in the maelstrom and for those trying to understand it.

Article Author: Ed Guthero

Ed Guthero has had a critically applauded career as a book and periodical designer, artist, and photographer, and a legacy ensured by years as a university lecturer. Here he shows another skill as an author. He writes from Boise, Idaho.