Amazing!

Albert J. Menendez January/February 2009

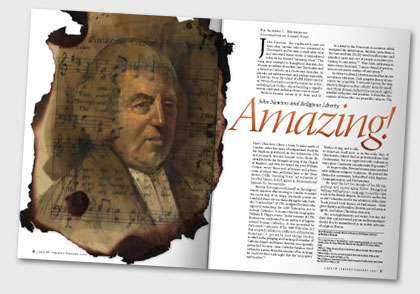

John Newton, the eighteenth-century slave-ship captain who was converted to Christianity and became a small-town vicar and renowned hymn writer, is remembered today for his beloved “Amazing Grace.” This song, once confined to Evangelical churches, has become an anthem of modern-day Christianity, and is heard in Catholic and Protestant churches, in parades and military events, and, perhaps especially, at funerals. It was the subject of a Bill Moyers special on PBS and has been recorded by numerous artists, including Judy Collins, whose haunting a cappella version captivated audiences from coast to coast.1

Newton became curate of St. Peter and St. Paul’s Church in Olney, a town 70 miles north of London. After five years of independent study for the Anglican priesthood, he was ordained in 1764 and promptly devoted himself to his flock. He identified with the Evangelical wing of the Church of England, and with his friend the poet William Cowper wrote thousands of hymns and poems, some of which were published later as the Olney Hymns. Oddly, “Amazing Grace,” not as popular as his other hymns, did not appear in denominational hymnals for two centuries.

Newton first expressed himself on the religious liberty question after moving to London to accept the rectorship of St. Mary Woolnoth parish on Lombard Street. He was there during the anti-Catholic “Gordon Riots” of 1780, instigated by those who opposed extending the 1689 Toleration Act to include Catholics. A recent Newton biographer, William E. Phipps, wrote: “In the summer of 1780, Newton was confronted by an outburst of bigotry toward Roman Catholics. It was provoked by Parliament’s extension of the 1689 Toleration Act that accepted Catholics in addition to all trinitarian Protestants. A riot led by Lord George Gordon resulted in the pillaging and burning of a number of Catholic chapels and homes. Newton was especially perturbed because some Catholic families lived within his parish. From the window of his vicarage he could see fires each night that the ‘no-popery’ mob had set.”2

In a letter to the Protestant Association, which instigated the disturbances, Newton wrote there is “no warrant from [God’s] word to inflict pains and penalties upon any sort of people in matters pertaining to conscience.”3 Years later, reflecting on these events, he noted, “I am no friend of persecution or restraint in matters of conscience.”4

In a letter to a friend, Newton insisted that he saw no value in toleration. Only complete liberty of conscience was acceptable. “I wish every person the same liberty in Religious matters, which I desire for myself. And I think Human Authority has not much right to interfere with pains and penalties, to force the consciences of those who are peaceable subjects. The Truth is strong, and as able to maintain itself now, as in the early days of Christianity, when it had no protection from Civil Government, but was oppressed with violence in every place. Constraint can only make Hypocrites.”5

As he grew older, Newton became more involved with different religious traditions. He praised the Methodist movement; hobnobbed with Baptists, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians.

He spent the last two decades of his life supporting and encouraging fellow Evangelical William Wilberforce’s campaign to end the slave trade in the British Empire. He lived to see the day in 1807 when the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade passed both houses of Parliament. With great dignity and humility, Newton passed away at age 82, just before Christmas that year.

His accomplishments are many, but the old slave-ship captain turned parson and hymnologist should also be remembered as an ardent advocate of religious liberty.

- For a superb history of “Amazing Grace” and its enduring popularity, see Steve Turner, Amazing Grace: The Story of America’s Most Beloved Song (New York: Harper Collins, 2002).

- William E. Phipps, Amazing Grace in John Newton (Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press, 2001), p. 162.

- William Barlass, Sermons on Practical Subjects (New York: Eastburn, 1818), p. 584.

- Newton, Letters, quoted in Phipps, p. 163.

- Bruce Hindmarsh, John Newton and the English Evangelical Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 320.