Are Children Mere Creatures of the State?

Charles J. RussoSarah Casson March/April 2024A growing threat to parental rights.

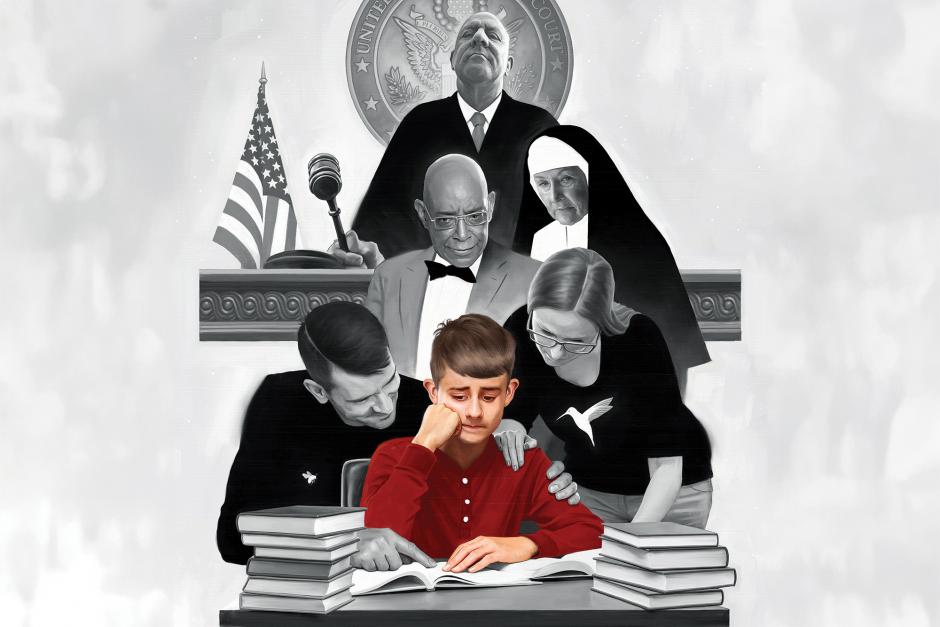

Illustration by Robert Carter

Almost a century ago, in Pierce v. Society of Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the rights of non-public schools to operate and of parents to have their children educated in them. At the heart of this 1925 landmark ruling the Court famously reasoned that “the child is not the mere creature of the state; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.” Most courts have since acknowledged the fundamental right of parents to direct the education and upbringing of their children. However, conflict has recently emerged on two issues within schools, with some courts standing Pierce on its ear and placing parental rights at great risk.

The first disputes about human sexuality curricula surfaced when some courts decreed that, by sending their children to public schools, parents forfeit their rights to challenge curricular content on this topic. More recent disagreements have addressed whether officials must inform parents when educators assist children, claiming to be transgender, who attempt to transition without parents’ knowledge or consent.

The first disputes about human sexuality curricula surfaced when some courts decreed that, by sending their children to public schools, parents forfeit their rights to challenge curricular content on this topic. More recent disagreements have addressed whether officials must inform parents when educators assist children, claiming to be transgender, who attempt to transition without parents’ knowledge or consent.

In light of these conflicts, the first of the three remaining parts of this article will briefly highlight leading cases about human sexuality curricula that reject Pierce. The second section reviews litigation over whether, consistent with Pierce, educators have the duty to inform parents when counseling minor students about gender identity or assisting those attempting to make life-altering changes via transitioning without parental knowledge, consent, or input. The third, and longest, part reflects on whether educators are unduly infringing on parental rights is these controversial areas.

Instruction about Human Sexuality

In the first of four cases on sexuality and curricula—the 1995 case of Brown v. Hot, Sexy and Safer Productions—parents in Massachusetts unsuccessfully challenged a highly explicit sex-education program presented to high school students. Among their concerns, parents objected to the facilitator having told students they were going to have a “group sexual experience, with audience participation” while using profane and lewd language describing body parts and excretory functions.

Upholding the authority of educators over curricular content, the First Circuit Court of Appeals wrote that the parental right to direct the upbringing and education of their children did not allow them to restrict the flow of information in public schools. The court affirmed that even though educators ignored a statute obligating them to provide notice prior to offering sexually explicit programs, they did not violate parental rights.

In 2006, in Fields v. Palmdale School District, the Ninth Circuit affirmed a California school board’s motion for summary judgment rejecting the claims of parents of first, third, and fifth graders who challenged educators who distributed a sexually explicit survey to their children. Among the questions were those asking children about: “8. Touching my private parts too much; 17. Thinking about having sex; 22. Thinking about touching other people’s private parts; 23. Thinking about sex when I don’t want to; 44. Having sex feelings in my body; 47. Can’t stop thinking about sex.”

The Ninth Circuit maintained that parents neither had a fundamental due process right to be exclusive providers of information on sexuality for their children or privacy rights to override public school officials as to the ideas to which students can be exposed. The court viewed the questions as rationally related to the board’s legitimate interests in effective education and the mental welfare of children. Two weeks later the United States House of Representatives adopted a resolution criticizing Palmdale in a vote of 320–91, decrying that it “deplorably infringed on parental rights.”

Later in the same year, in C.N. v. Ridgewood Board of Education, the Third Circuit reached a similar result. The court affirmed a grant of summary judgment in favor of a school board in New Jersey when parents of seventh to twelfth graders objected to a voluntary, anonymous survey used to gather information about drug and alcohol use as well as sexual activity. The survey also included questions about students’ experiences of physical violence, suicide attempts, and personal associations, including parental relationships. Explicitly rejecting Pierce, the court declared that its rationale “does not extend beyond the threshold of the school door,” concluding that officials did not violate the rights of students to privacy or of parents to make important decisions about the care and control of their children.

Two years later, in Parker v. Hurley, the First Circuit, in another suit from Massachusetts, affirmed a grant of summary judgment in favor of a school officials when parents challenged the inclusion of material on same-sex marriage in a kindergarten class. Rejecting the claims of two sets of parents, the court ignored the same commonwealth statute mandating notice in Brown. The court thought that educators did not significantly limit either the parents’ rights to due process or free exercise of religion in allowing teachers to use books portraying diverse families, including ones in which both parents were of the same sex.

Transgender Challenges

In the first of two 2023 disputes from Maryland, John and Jane Parents 1, John Parent 2 v. Montgomery County Board of Education, a divided Fourth Circuit rejected claims that a school board’s guidelines for developing “student gender identity support plans” violated parents’ fundamental right to raise their children. The court said the parents had not shown that they had sustained any injuries: they had not alleged that their children identified as transgender or that educators kept information from parents.

Similarly, in Mahmoud v. McKnight another federal trial court in Maryland denied the claims of Muslim and Catholic parents along with an association including members of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints, Protestants, and Jews who sued the Montgomery County Board of Education. The parents charged that educators forced their pre-K-8-aged children to read books promoting transgender ideology and encouraging gender transitioning. The parents specified that school officials did not follow state law and failed to fulfill a promise to notify parents of their right to opt their children out of these classes.

The court refused to enjoin the board’s policy, unswayed by arguments that it interfered with parental rights to direct the upbringing of their children by not offering age-appropriate instruction consistent with their faiths, and that the policy was inconsistent with science demonstrating that most young people who experience gender dysphoria outgrow it. The court commented that the policy did not violate the parents’ right to free exercise of religion because parents lacked a fundamental due process interest in directing their children’s upbringing by opting them out of instruction conflicting with their beliefs. The parents have appealed to the Fourth Circuit.

On the other hand, also in 2023, in Tatel v. Mt. Lebanon School District, a federal trial court in Pennsylvania reached the opposite result. The court refused to dismiss claims filed by the mothers challenging a teacher and officials for discussing gender dysphoria and transgender transitioning with their first graders. Moreover, the mothers charged that the school board had a de facto policy of not allowing parents to opt their children out of such instruction in violation of their First and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

The court noted that educators lacked a compelling interest that would justify ignoring these maternal concerns. Instead, the court said educators must inform parents about activities potentially impacting and shaping the character or identity of their children. The court emphasized that because educator conduct on gender identity reached “the heart of parental decision-making,” it was constitutionally significant. At the same time, the court rejected educators’ motions for summary judgment on the mothers’ substantive and procedural due process claims, Fourteenth Amendment familial privacy charges, and First Amendment free exercise allegations, citing the educators’ violation of board policy in ignoring parental rights.

Reflections

At issue in the cases reviewed above, and others not discussed here, is who has primary responsibility to care for minors living at home. The state, of course, through public schools, has a legitimate interest in ensuring an educated citizenry by addressing such topics as human sexuality. Still, parents have a fundamental right to raise their children consistent with their beliefs and values. The trick, then, is to strike the proper balance between the increasingly conflicting interests of parents and educators in some districts. Difficulties arise when educators fail or refuse to take parental concerns into account by allowing parents to opt their children out of instruction. In many instances, parents deem this instruction inappropriate either because they wish to address these sensitive topics at home or because exposing their children to these materials conflicts with parents’ rights to the free exercise of religion.

When educators include lessons on human sexuality in curricula, two concerns surface. First, as in Brown and Parker, it seems prudent for educators to comply with statutes mandating parental notification, allowing parents to opt their children out of explicit subject matter they deem incompatible with their values. Second, again conceding that students need to know about human sexuality, instruction must be age appropriate. For instance, in Parker parents of a kindergartner unsuccessfully challenged his being taught about same-sex unions. Further, in Palmdale the survey asked first, third, and fifth graders questions about sexuality that children, especially in the two younger grades, likely did not even comprehend. It is unclear how young children in either situation might have benefited from exposure to such material.

Turning to issues surrounding transitioning and gender identity, educators certainly have a duty to look after student well-being. Regardless, one must ask whether educators exceed their authority in not informing parents about what is happening with their children. In a few instances, educators may have legitimate fears about the safety of students whose parents do not accept that their children seek to transition. In these instances, educators have the option of contacting child welfare agencies. Yet, absent such concerns about the welfare of students, when educators not only allow, but encourage, students to dress differently than at home as well as to use the pronouns of their choice in schools without informing or consulting their parents, they may be driving wedges between parents and their children.

If educators wish to help minors deal with issues associated with transitioning and gender identity, they must involve their loving parents who have cared for them since birth. By working with parents, educators can, and should, help students realize that by taking hormones and/or considering surgery they are contemplating life-altering steps at an age when they cannot fully comprehend what they are attempting to do. Additionally, as most children overcome their gender dysphoria as time passes, it is unclear what is to be gained by encouraging students to take such major steps quickly, without parental involvement.

Rather than rushing children toward permanent transitioning and hormone treatments, educators should encourage students to speak with appropriate medical and psychological professionals, along with their parents. When educators fail to include parents on crucial matters involving their children—especially minors unlikely to understand fully the life-altering consequences of their planned actions—educators’ behavior can be harmful in two overlapping ways.

First, not involving parents undermines their fundamental rights by excluding them from important decisions in the lives of their children. Second, excluding parents risks damaging familial bonds irreparably; when outsiders interfere in such intimate matters, it sends the message to young people, even if unintended, that they can neither confide in, nor trust, their parents on matters of utmost importance.

Even if educators are acting with good faith, they should pause, acknowledging that these students are not their own children. Teachers and school officials should respectfully defer to the judgment and rights of parents who gave these students life and served as their first teachers. Because, after all, children are not the mere creatures of the state.

Article Author: Charles J. Russo

Charles J. Russo, M.Div., J.D., Ed.D., is the Joseph Panzer chair in education in the School of Education and Health Sciences, director of its Ph.D. program in educational leadership, and research professor of law in the School of Law at the University of Dayton. He can be reached at crusso1@udayton.edu.

Article Author: Sarah Casson

Sarah Casson, B.A., B.S.W., M.A.T., holds a J.D. from University of Dayton School of Law, where she served as a Dean’s Fellow and a member of the UDSL Law Review. Since 2012, she has taught English Language Arts to seventh and eighth graders in the public school system.