Aristotle and Darwin and First Causes

Clifford R. Goldstein May/June 2018Santana Was Wrong: Those Who Remember History Can Still Be Doomed to Repeat It

In contrast to his comparatively stick-in-the-mud predecessor, Benedict XVI, Pope 266, Pope Francis, is quite the progressive, at least as progressive as one could be as the head of an institution sitting on about 1,500 years of tradition. But whether dissing capitalism, railing against climate change, or trying to loosen up attitudes about homosexuality and divorce, Pope Francis is at least attempting to set a somewhat “progressive” direction for his church.

And though not the first bishop of Rome to do so, Pope Francis has also been pretty open about the theory of evolution and how it can fit snugly with his Roman Catholicism. Not long after he first came into office, the pope told an audience from the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in Vatican City that he didn’t see evolution as inconsistent with creationism.

“The evolution in nature is not opposed to the notion of creation, because evolution presupposes the creation of beings that evolve,” Pope Francis said. He even elaborated more: “When we read in Genesis the account of creation, we risk imagining that God was a magician, with such a magic wand as to be able to do everything. However, it was not like that. He created beings and left them to develop according to the internal laws that He gave each one, so that they would develop, and reach their fullness.”

Both Pope Pius XII and John Paul II made similar overtures toward evolutionary theory, the prevailing scientific dogma of our time. Though numerous factors certainly have been motivating this attempted reconciliation between faith and science, it doesn’t take a biblical prophet to understand the subtext: the heresy trial of Galileo Galilei in the seventeenth century, when one of Pope Francis’ predecessors was ready to torture and imprison an old man for teaching that the earth moved around the sun, instead of the sun moving around the earth, as Rome—following the best science of the time—taught.

However, an outrageous irony exists in Rome’s unofficial acquiescence of evolutionary theory, all in an attempt to avoid another embarrassing blunder and public relations disaster as the Galileo trial had been for the Roman Catholic Church. And that is, by embracing evolution, by attempting to incorporate it into faith, Rome is simply repeating the same error that Galileo’s inquisitors did 400 years ago. Far from learning from those mistakes, Rome is making the same one again.

Aforesaid Errors and Heresies

As with many things, it was complicated. Numerous factors—from Vatican court intrigues, to intellectual rivalry, to the stresses of the Protestant Reformation—congealed into the infamous heresy trial of Galileo in 1616. Not helping matters was that some of Galileo’s arguments weren’t so strong (some were, in fact, wrong), and his personal character flaws didn’t help matters either. Also, aside from the scriptural issues, some impressive logical and empirical reasons to question Galileo’s position existed. All these factors led to some of the most infamous words in intellectual, scientific, and religious history, Galileo’s recantation: “I must altogether abandon the false opinion that the sun is the center of the universe and immovable, and that the earth is not the center of the world, and moves . . . . I abjure, curse, and detest the aforesaid errors and heresies.”

The “aforesaid errors and heresies” were in his book Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, in which he made his case for the Copernican model of the universe. What follows are a few excerpts from the book, which had been written in the form of a dialogue:

“This is the cornerstone, basis, and foundation of the entire structure of the Aristotelian universe, upon which are superimposed all other celestial properties—freedom from gravity and levity, ingenerability, incorruptibility, exemption from all mutations except local ones.”

“I might add that neither Aristotle nor you can ever prove that the earth is de facto the center of the universe; if any center be may be assigned to the universe, we shall rather find the sun to be placed there, as you will understand in due course.”

“But seeing on the other hand the great authority that Aristotle has gained universally; considering the number of famous interpreters who have toiled to explain his meanings; and observing that all other sciences, so useful and necessary to mankind, base a large part of their value and reputation upon Aristotle’s credit.”

“I do not mean that a person should not listen to Aristotle. . . . I applaud the reading and careful study of his works, and I reproach only those who give themselves up as slaves to him in such a way as to subscribe blindly to everything he says and take it as an inviolable decree without looking for any other reasons.”

“You are . . . angry that Aristotle cannot speak; yet I tell you that if Aristotle were here he would either be convinced by us or he would pick our arguments to pieces and persuade us with better ones.”

Who and what is the focus of the dialogue? Moses? Jesus? Paul? No, the focus was Aristotle, whose teachings, and Galileo’s refutation of those teachings, is a key component of the Dialogue. Moses, Jesus, Paul are never mentioned. The phrase “Holy Scriptures” appears only twice in the book, in contrast to “Aristotle,” who appears in the pages about 100 times.

The Darwin of That Day

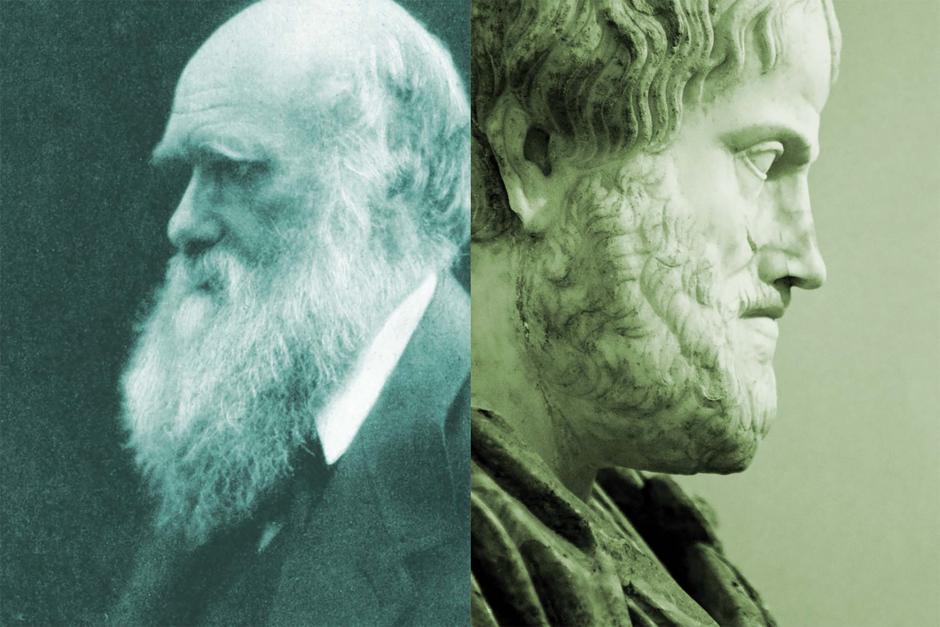

The importance of this point cannot be overestimated. Galileo wasn’t fighting against the Bible, but against an interpretation of the Bible dominated by the prevailing scientific dogma, which for centuries had been Aristotelianism. Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) was the Charles Darwin of that era, all but deified in ways that even Darwin is not today. No matter how much many intellectuals remain under the Englishman’s jinx, they will criticize his work. Even such a Darwinian exponent as Richard Dawkins could write: “Much of what Darwin said, in detail, is wrong.”

In contrast, in the era of Galileo, people were less ready to contradict Aristotle, whose writings intellectually plundered and pillaged the culture of the time. Students entering colleges in the Middle Ages were told to discard any teaching that went against “the philosopher,” as Aristotle had come to be known. “The writings of Aristotle,” wrote William R. Shea, “that had earlier stimulated lively discussion were increasingly turned into rigid dogma and a mechanical criterion of truth. Other philosophical systems were viewed with suspicion.”

Just as today’s mania to interpret everything—from the shape of a dog’s ear, to our “natural tendency to be kind to our genetic relations but to be xenophobic, suspicious, and even aggressive toward people in other tribes”—in a Darwinian context, back then Aristotle’s teaching was the filter from which everything, from the motion of the stars to the nature of the bread and wine in the Eucharist, was to be understood.

Nevertheless, medieval scholars had to twist, turn, distort and obfuscate in order to meld Aristotle’s science, philosophy and cosmology with biblical doctrine, much in the same way people today try to harmonize Jesus with Darwin. No one worked at it more “successfully” than Italian Dominican friar and priest Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225-1274), who all but converted the pagan Aristotle into a mass-going-indulgence-offering-Mary-adoring Roman Catholic. Though some opposition existed (and was growing) against the Aristotelian worldview, at the time of Galileo Aristotle’s writings were the filter through which the works of God in nature were to be viewed. “With the Church’s gradual acceptance of that work,” wrote Richard Tarnas, “the Aristotelian corpus was elevated virtually to the status of Christian dogma.”

Aristotle’s Cosmos

The only problem? That dogma was wrong. The four “heresies” that got poor Galileo into so much trouble weren’t even biblical doctrine; they were “scientific” teaching imposed upon the Bible, exactly what theistic evolution does today.

For example, among the charges that the Inquisition hurled at Galileo because of the book was: “the proposition that the sun is in the center of the world [i.e., the universe] and does not move from its place is absurd, and false philosophically, and formally heretical, because it is expressly contrary to Holy Scripture.”

Technically, Galileo was wrong. The sun is not the center of the universe, but only of our solar system, which itself hovers in the outer burbs of the Milky Way, one of billions of galaxies careening across what’s (probably) infinity. Yet where does Scripture locate the sun in relation to the cosmos? What inspired words say that it is, or is not, the center of the universe? How could Galileo be charged with heresy on a topic the Bible never addressed?

The answer is easy: Galileo’s heresy wasn’t against the Bible but against an interpretation of the Bible based on science—a scary parallel to what theistic evolutionists are doing today. It didn’t matter that the Bible never said that the sun was at the center of the universe. Aristotle did, and because the Bible was interpreted through this, the prevailing scientific theory, an astronomical point never addressed in Scripture had become a theological position of such centrality that the Inquisition threatened to torture an old man for teaching contrary to it.

Another heresy was Galileo’s contention that the sun was “immovable” (technically wrong). Though the church at least had some Scripture to back up its claim, such as Psalm 19, that text itself is a poetical expression of the power of God as revealed in the heavens. The psalm is no more cosmology than Jesus’ words—“Why are you thinking these things in your hearts?” (Luke 5:22, NIV)1—were physiology, or any more than biblical texts about the sun rising or the sun setting are cosmology, either. In fact, the language of “sunrise” and “sunset” in the Bible took on the importance that they did only because of the incorporation of false science into theology, exactly what’s happening today, but with Darwin, not Aristotle. Had the church not adopted Aristotle’s cosmology, and not made a theological issue out of what the Bible never addressed, Roman Catholicism might have been spared the embarrassment of the Galileo affair.

Besides the motion and position of the sun, Galileo’s condemnation included the charge that he taught that the earth was not the center of the universe.

Yet where does the Bible ever plop earth into the center of the cosmos? This view is Aristotle’s, not the Scriptures’. How ironic that, supposedly defending the faith, the church accused a man of heresy for opposing a long-established scientific theory, a theory never expressed in Scripture and that, in fact, turned out to be wrong.

Finally, Galileo asserted that the earth moved. Wasn’t this view in conflict with such texts as Psalm 93:1, which states that “surely the world is established, so that it cannot be moved” (NKJV)? 2

The only problem, however, is that numerous other texts, from those about earthquakes (Amos 1:1; Luke 21:11), to the earth one day “shall reel to and fro like a drunkard, and shall totter like a hut” (Isaiah 24:20, NKJV), clearly don’t teach an immovable planet.

The motion in the texts about the earth reeling “to and fro like a drunkard” and the like isn’t dealing with the earth’s orbits or axis. Neither was the nonmotion in the texts about God establishing the earth so that “it cannot be moved” dealing with terrestrial orbit or axis, either. The verses were about the power and majesty of God as Creator and as Judge; they weren’t about cosmology any more than Peter’s words to Ananias, “Why hath Satan filled thine heart to lie to the Holy Ghost?” (Acts 5:3) were about anatomy and physiology.

Aristotle and Darwin

In short, Galileo’s story, contrary to the common view, is an example of the church in antiquity doing what the church today is doing: interpreting the Bible through prevailing scientific dogma. In Galileo’s day that dogma was Aristotelianism; in ours, it’s Darwinism, or whatever the latest version happens to be.

One major difference, however, exists between what the church did then, with the Aristotelian view of the cosmos, and what theistic evolutionists do today, with the Darwinian one. While the earth-centered view of the cosmos isn’t addressed in the Bible (that model could have been correct without contradicting Scripture), evolution contradicts the Bible in every way possible. Aristotle could have been right; it would have made no difference. But if Darwin is right, Jesus is wrong.

In the introduction to the twentieth-century translation of the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Albert Einstein wrote the following: “The leitmotif which I recognize in Galileo’s work is the passionate fight against any kind of dogma based on authority.”

Einstein was correct. The trial of Galileo was an example of what can happen when someone fights against “any kind of dogma based on authority.” But the dogma was based on the authority of science, a dogma as unrelenting and intolerant in the seventeenth century as it is today. Far from revealing the dangers of religion battling science, the Galileo trial reveals the dangers of religion capitulating to it—exactly what Rome is, again, doing.

The Roman Catholic Church, during the trial of Galileo, was defending, not the Bible, but a false interpretation of the Bible created by an unfortunate conflation of faith with science. This is the exact mistake that Pope Francis is making today, as well, with his statements about the supposed harmony between evolution and the Bible. By acquiescing to the latest scientific dogma, and seeking to incorporate that dogma into Catholic belief, Pope Francis, far from avoiding the footsteps of the Roman inquisitors of Galileo, is unfortunately following right in their footsteps.

1 Bible texts credited to NIV are from the Holy Bible, New International Version. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

2 Bible texts credited to NKJV are from the New King James Version. Copyright © 1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Clifford Goldstein is the author of Baptizing the Devil: Evolution and the Seduction of Christianity, available on Amazon.com. He writes from Mount Airy, Maryland.

Excerpt from Baptizing the Devil:

Comedian Steve Martin portrayed Theodoric of York, a medieval barber who also practiced medicine. Theodoric tells the mother of a patient not to worry, that even though science is not exact, “we are learning all the time. Why, just 50 years ago they thought a disease like your daughter’s was caused by demonic possession or witchcraft. But nowadays we know that Isabelle is suffering from an imbalance of bodily humors, perhaps caused by a toad or a dwarf living in her stomach.”

Because we have been etched out of finer, more advanced stuff than were previous generations, we smugly mock their ignorance. But the vast gap between what we know and what can be known should help us realize that even with the Large Hadron Collider, the Human Genome Project, and the Hubble Space Telescope, we’re only a few notches up the intellectual food chain from either Theodoric of York or even Galileo’s inquisitors.

Whatever lessons can be milked from Galileo’s “heresy,” one should be that science never unfolds in a vacuum but always in a context that, of necessity, influences its conclusions. Whether seeking the Higgs Boson, or dissing Galileo’s Dialogue, scientists work from presuppositions and assumptions. Ideally, over time, they assume that their later assumptions are closer to reality than were the earlier ones. But they just assume that—maybe with good reasons, but they are still just that, assumptions. The story of science, in Galileo’s day and in ours, is rife with scientists who had good reasons for theories, and the assumptions behind those theories, that are now believed to be wrong.

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.