Built on Faith: The Bible and the American Republic

Bettina Krause March/April 2022INTERVIEW

A new museum in the birthplace of American democracy highlights a neglected history

It’s a high-tech, $60 million, twenty-first-century museum devoted to values extracted from an ancient book. The American Bible Society’s Faith and Liberty Discovery Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, opened in May 2021 and sits in the middle of America’s “most historic square mile.” From the museum’s entrance you can look left toward Independence Hall, a UNESCO World Heritage site where the Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution were debated and adopted. Look right, and the view extends down Independence Mall toward the National Constitution Center. Inside, the interactive exhibits were designed by Local Projects, an award-winning Manhattan-based media and design company known for its high-profile projects around the globe.

But from the very beginning, the key challenge for the American Bible Society was not location or design—it was content. For five years leading up to the opening of the museum, an international group of some 30 scholars, representing a cross-section of religions and perspectives, helped shape the story the museum would tell. Their task? To engage visitors—of all faiths and none—in a narrative that’s increasingly overlooked in discussions of America’s history: the influence of the Bible on the social, legal, and political character of the American republic.

Liberty editor Bettina Krause recently talked with Alan Crippen, senior advisor for the museum, about the challenges of explaining the role of faith in the American experiment.

Bettina Krause: Congratulations on the opening of the center. Can you tell me more about the American Bible Society and how this project came about?

Alan Crippen: Well, the American Bible Society was founded 205 years ago, and some of our founders were also founders of the American republic. Our first president was Elias Boudinot, who was one of the presidents of the Continental Congress. He’s not a household name like Jefferson, Adams, Madison, or Washington, but when you dig into his history, you see he’s a major player. He mentored Alexander Hamilton, for instance. The second president of the Bible Society was John Jay, which is a name you know—a very influential American founder. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall was also one of the early vice presidents of the Bible Society, as was John Quincy Adams.

The Bible Society movement began in England with the British and Foreign Bible Society. The American Bible Society was patterned after that and had the goal of distributing the Scriptures throughout the emerging American republic. Obviously, the primary mission of the society was to share the eternal verities of Scripture, eternal truths, and to nurture the salvation of souls. But there was also a secondary mission, particularly given the American context where we have a disestablished church. In England, there’s a state church that, in a sense, provided the moral, spiritual, and ethical ballast for the state. That’s the European model. But in America the church is disestablished, so we depend then on voluntary associations to provide that ballast. I think that’s why so many American founders were interested in an American Bible Society. They saw the Bible as a source of public virtue, the kind of virtue that’s necessary to sustain and perpetuate liberty, along with the republican—small “r” republican—forms of government.

I say all this to give context. Both this religious and civic mission is in the DNA of the American Bible Society. In 2015, after 199 years in New York City, the society moved its headquarters to Philadelphia. And this locus was not lost on the leadership of the society. We looked at the piece of property we’d acquired—in the historic district—and we asked the question: “Is there something we can do that’s appropriate, that would involve outreach, that would tell the story of the Bible in America and its role in our republic’s origin and development?”

In wrestling with that question came a vision for establishing an outward-facing institution that would invite people of all faiths, or of no faith, to come in and to explore. To see what the Bible is all about and how it relates to this country we call America.

Bettina: So when someone walks through the doors of this museum, what are they going to experience? What are they going to learn? How will they interact with the exhibits?

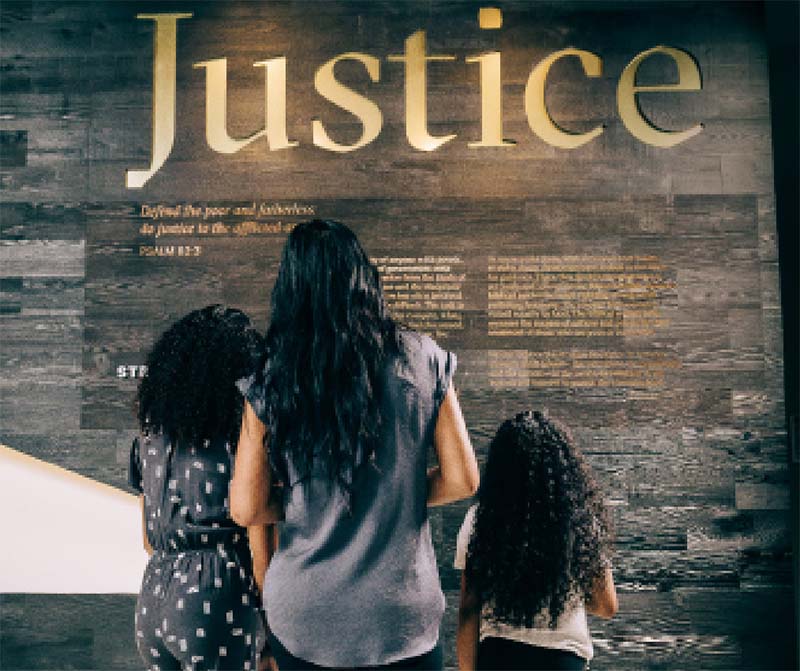

Alan: Well, let me start back with our thesis statement. Our thesis is that faith guides liberty toward justice. That is what I would hope visitors walk away with—an appreciation that liberty, at least in the American experience, has been influenced, shaped, and directed by faith.

There were two major revolutions in the eighteenth century: the French Revolution and the American Revolution. The American Revolution, it was bloody; it was hard fought and hard won. But it produced a pretty stable republic that has endured. The French Revolution is another story. The French Revolution was also a revolution committed to liberty, but it devolved into a horrendous bloodbath, with the horror of the guillotine, executions, martyrs, and tyrants. It ended with the global wars led by Napoleon Bonaparte that left some 7 million people dead, all in the name of liberty. And the constitutional order it produced was not as stable. I think we’re on republic number five in France.

There were both contemporary and later scholars who asked, “What was the difference between the French and American revolutions?” Alexis de Tocqueville, of course, was one of a number who identified faith as one of the key differences. In the 1830s Tocqueville came to America and wrote a book called Democracy in America. He had some interesting things to say about faith and its role in sustaining and perpetuating the American constitutional order.

So, in big-picture terms, that’s what we are saying. The Bible, we would argue, is essentially a freedom book. The Scriptures are fundamentally about spiritual freedom, but its principles are also about these other freedoms that we enjoy as Americans: religious freedom, economic freedom, political freedom, civil freedom, civil rights.

Bettina: How are these ideas reflected in the museum’s exhibits?

Alan: When we built the Faith and Liberty Discovery Center, we designed it to have six galleries, with each one dedicated to a different virtue. We start with faith, and then we go to liberty and then justice, hope, unity, and love. We picked these values as American values, values that have united us as Americans and that were central to the founding. We also have a Welcome Gallery, where there’s a graphic exhibit that focuses lenses on foundational documents, ranging from the Declaration to the Constitution to the Articles of Confederation, to Pennsylvania’s early Colonial constitution, and the correspondence of various founders. And from these documents, the values—literally, the words—are picked out and lifted up. What we’re trying to say is that these values, which we build our galleries around, are foundational to American order, and they were present at the beginning.

Our hope is that people of all faiths or no faith will come and visit, and they’ll at least discover that the Bible had a positive role in inspiring leaders, reformers, and other great Americans, known and unknown. We would like the visitor to imagine, “What would America be without the Bible?” Would, for instance, the American Revolution have happened? Probably not. Or if it had, maybe it would have been more like France’s. Where would the abolitionist movement have been without the Bible? Where would the civil rights movement have been without a Martin Luther King Jr.?

Bettina: It’s a difficult project you’re attempting when it comes to someone who doesn’t come from a Judaic or Christian background. I’m sure you’ve heard the criticism that the Discovery Center is an attempt by a Christian organization to lay claim to America’s history. I know that that’s not the intent, but how do you respond to someone who is coming to this topic from a profoundly different worldview?

Alan: Well, we’ve designed the Faith and Liberty Discovery Center to be a history museum. It doesn’t have an explicit religious purpose. The Bible Society does—it’s one of America’s oldest religious nonprofits with a religious mission. But the Faith and Liberty Discovery Center has an educational mission, and its content deals with religion in American history. I guess people might construe it as having a religious mission, but that isn’t the case. The reality is that you really can’t understand America’s political, social, and cultural history without some reasonable working knowledge of the impact of Judaic and Christian faiths. So that’s our posture and our approach.

I think some people have a hard time understanding that because we live in such a secularized world that wants to bifurcate religion from culture, that wants to sanitize religion from culture. You really can’t do that. It’s just not the human experience. They go together and we need to understand that.

Bettina: The Bible Society is nonpolitical and has been for more than two centuries. But how can you tell the story you’re telling without playing into current political realities? I’m thinking, for instance, of the Christian nationalism on display during the January 6 attack on the Capitol. How do you tell this important story of the role of the Bible in American history without playing into those combustible narratives?

Alan: I liked the way you describe it. Yes, political narratives in America couldn’t be more combustible, and this was a reality that was already well advanced when we started on this project. We were conscious that we had the opportunity to speak into this reality, hence our focus on the values that unite us. One of our galleries is devoted to unity, illustrating that these are the United States, and the Constitution exists to create a more perfect union. Not a perfect one, but a more perfect union.

But you’re right. The Bible Society is absolutely apolitical, yet in creating a history museum we had to acknowledge that even history has been politicized. So we have worked very hard to be apolitical. Faith must transcend politics. We’re trying to tell the story of how the Bible has influenced individuals in key historical and personal moments without being political.

Now, we do have to deal with political material, because it’s a museum about civic and political history. We talk, for instance, about how Martin Luther King Jr., and other civil rights leaders took inspiration from the Bible and advanced Herculean political reforms. The same holds true for abolitionists or even those who took part in the American Revolution. But we have intentionally avoided any contemporary issues. We don’t want to create obstacles for people to trip over and miss the larger point.

Now, that said, I think it’s impossible for any thinking person to walk through the Faith and Liberty Discovery Center and not begin to connect dots with some current contemporary issues. We want that. We want people to be able to reflect, to consider and apply, to reason, to engage in civil dialogue with one another and deescalate the combustible atmosphere that we have. We have installed what we call “conversation booths,” where the visitor who wants to connect these dots can go into these booths and hit a record button. They’re guided in sharing their thoughts on whatever they want to talk about. That then becomes material we can curate and use for future exhibits. Again, our goal is to create a place for engagement, for reflection, and for conversation without being politicized.

Article Author: Bettina Krause

Bettina Krause is the editor of Liberty magazine.