Could it Be in America?

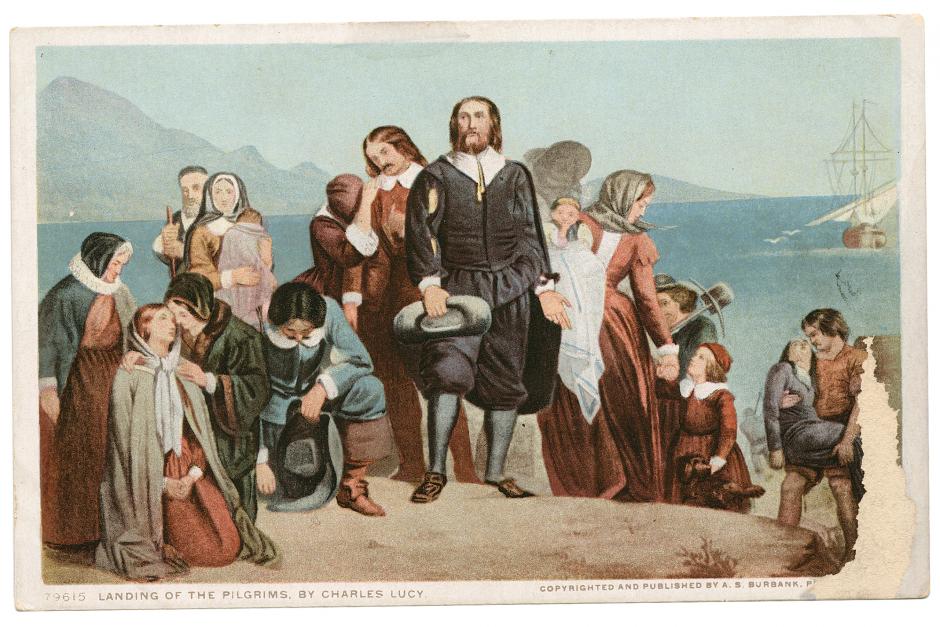

Lyndon McDowell May/June 2021Consequential circumstances can sometimes be triggered by inconsequential events. Given the versatility of wind and weather, it might seem of little consequence that the Mayflower landed at Plymouth Rock rather than far to the south near Virginia, but nevertheless the event has etched itself deeply into the historical consciousness of the country. The Puritan settlement represented the virility and adventurism of the early American experience.

At the bicentennial celebrations of the landing, Daniel Webster, the great constitutional lawyer, waxed Ciceronian describing the Pilgrim virtues: “Who would wish for other emblazoning of his country’s heraldry, or other ornaments of her genealogy, than to be able to say that her first existence was with intelligence, her first breath the inspiration of liberty, her first principle the truth of divine religion?”1

Eloquent indeed. A model for aspiring orators. A subject for study by students of a country and a history that as yet had not been written.2 But “truth of divine religion”? An “inspiration of liberty”? The fruit of “intelligence”? Or were they, to use a term we know only too well elsewhere in our day, al Qaeda Christians?

In December of 1641 a copy of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties was proposed by Puritan leader and lawyer Nathaniel Ward. It is recognized as “an important source of rights recognized in the first ten amendments to the American constitution, or Bill of Rights.”3 Those early settlers voted a carefully crafted statement defining their Christian community:

“The free fruition of such liberties Immunities and priveledges as humanitie, Civilitie, and Christianitie call for as due to every man in his place and proportion; without impeachment and Infringement hath ever bene and ever will be the tranquillitie and Stabilitie of Churches and Comonwealths. And the deniall or deprivall thereof, the disturbance if not the ruine of both.”4

The words ring with intelligence. They exhale the breath of liberty. They resound with the truth of divine religion. But a malefic threat is there in which only a prophet would have seen mirrored the fires of Smithfield or heard again the tolling bell of St. Bartholomew’s Day. The people were free to believe as long as that belief was in harmony with what was believed.5

John Leland (1754-1841), a Baptist minister and an important figure in the fight for religious liberty in America, would later warn of what I suggest is the al Qaeda principle. He listed three principles of oppressive governments: those founded on birth and property, those founded on aristocracy, and those that require religious tests to ensure religious conformity. Of the third one he wrote that it “was the error of Constantine’s government, who first established the Christian religion by law, and then proscribed the pagans and banished the Arian heretics. The error also filled the heads of the anabaptists in Germany. . . . The same error prevails in the see of Rome, where his holiness exalts himself above all who are called gods . . . , and where no Protestant heretic is allowed the liberty of a citizen. This principle is also pled for in the Ottoman Empire, where it is death to call in question the divinity of Mahomet or the authenticity of the Alcoran. . . . The same evil has twisted itself into the British form of government; where . . . no man is eligible to any office, civil or military, without he subscribes to the 39 articles and book of common prayer.”6

In short, the al Qaeda principle is that punishments and disabilities are imposed on those who disagree with the state’s definition of what is to be believed and practiced. The argument is simple: Since Christianity and the Scriptures are of divine origin, anyone opposed to them is guilty of criminal folly. The conclusion was without appeal, and its fruit would be despotism.

England had set many examples. When William Prynne proclaimed Archbishop William Laud to be a servant of the pope and the devil, he was jailed, branded on both cheeks, and his ears cut off. 7 Even the captain of the Mayflower is said to have refused to have a King James Bible on board his ship. For him and therefore for his passengers as well, the Bishop’s Bible was the only true Word of God. Thus the genetic religiosity of the Puritans disposed them to a cruel dogmatism that infected the colony they founded.

Although the laws they wrote were expressed as liberties and not “in the exact forme of Laws, or Statutes,” they added: “Yet we do with one consent fullie Authorise, and earnestly intreate all that are and shall be in Authoritie to consider them as laws, and not to faile to inflict condigne and proportionable puinishments upon every man impartiallie, that shall infringe or violate any of them.”8

Citizens were free to believe and practice as they wished unless it differed from what the community said was truth. Then some Baptists arrived and the al Qaeda logic came into play.

“Forasmuch as experience hath plentifully & often proved that since the first arising of the Ana-baptists about a hundred years apart they have been the Incendiaries of Common-Wealths & the Infectors of persons in main matters of Religion, & the Troublers of Churches in most places where they have been, & that they who have held the baptizing of Infants unlawful have usually held other errors or heresies together therwith (though as hereticks used to doe they have concealed the same until they espied a fit advantage and opportunity to vent them by way of question or scruple)”—such people “who appear to the Court” to be “willfully and obstinately to continue, . . . shall be sentenced to Banishment.”9

The consequences were not of inconsequence for Thomas Gould. In October 1655 he refused to have his baby sprinkled and christened. Over the next three years he was in and out of court, until, finally, on May 27 he was banished under penalty of perpetual imprisonment. He chose imprisonment rather than banishment, but, fortunately for him, news of the proceedings reached England, appeals were made, and he, and others with him, were finally released.

Obadiah Holmes was less fortunate. Tied to a post, he received 30 lashes with a three-thronged whip of knotted cord, wielded with both hands. The whipping was so severe that when taken back to prison his lacerated body could not bear to touch the bed. For many days he was compelled to rest propped up on his knees and elbows.

Mary Fisher and Anne Austin were Quakers who came by ship to Boston. Somehow news of their arrival preceded them, and the deputy-governor boarded the ship, searched the women’s trunks and chests, and took away their books and burned them. Soon after the book burning the women were taken from the ship and imprisoned. Their pens, ink, and paper were taken from them. Under pretense of finding out if they were witches or not, they were stripped naked, and their prison window was boarded up so that there could be no communication with anyone outside.

After five weeks of imprisonment they were taken aboard ship again and William Chichester, the master of the vessel, was bound by a 100-pound bond to take them away.

They were fortunate. A “Vagabond Act” stated that any vagabond Quaker was to be tied to a cart’s tail and flogged through several towns. Domiciled Quakers, if they refused to leave, were then treated as vagabond. Anne Coleman, Mary Tomkins, and Alice Ambrose were condemned. On a cold winter’s day the women were stripped from the middle and upward, and tied to a cart, cruelly whipped with a combined 330 lashes and sent on a journey of some 80 miles. In Salisbury, however, the people took pity on them and released them.

Quaker Elizabeth Hooton received a similar sentence. In midwinter she was whipped behind a cart through Cambridge, Watertown, and Dedham. The terrible nature of the torture can be visualized in the fact that, being midwinter, the victim’s wounds became cold and sometimes frozen. This made the torture intolerably agonizing.10 One wonders how a community of Christian people could become so hardened and insensible to true Christian sensibility.

Salem, like most New England settlements, was founded on a popular theocracy—the government was in the hands of the church members. The Covenant of 1629, composed of only three lines, was the sshortest of any. It read: “We Covenant with the Lord and one with another; and do bind ourselves in the presence of God, to walk together in all his waies, according as he is pleased to reveale himselfe unto us in his Blessed word of truth.”

Again the al Qaeda principle found expression. John Hathorne, the instigator and judge of witch trials, was described as “a very religious man.” Mary Eastey was brought before him and accused of witchcraft. Something of the agony of her husband, Isaac, can be felt in his later testimony: “Mary my wife,” he testified, “was near five months imprisoned, all which time I provided maintenance for her at my own cost & charge, I went constantly twice a week to provide for her what she needed. Three weeks of this five months she was imprisoned at Boston & I was constrained to be at the charge of transporting her to & fro.” Mary Eastey was finally hanged on September 22, 1692. Before she died, she testified, “If it be possible, no more innocent blood be shed. . . . I am clear of this sin.” Hanged with her were Martha Corey, Margaret Scott, Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Wilmott Redd, Samuel Wardwell, and Mary Parker.

Between March of 1692 and October 8 some 20 people were executed for the sin of witchcraft. One of these, Sarah Good, had a nursing child, yet was tried and imprisoned for four months and then hanged. The child died in prison. Another child about 5 years old was not only imprisoned but also chained.

If the impression is held that Salem was a little backwater Hicksville, this would be incorrect. It had a busy port of adventurous sailors and later, after the revolution, became the wealthiest city per capita in the United States, with a motto that read Divitis Indiae usque ad ultimum sinum (“To the rich East Indies until the last lap”).

Slowly people began to question the cruelty of such proceedings and reparation was given to the families of those who had suffered; some 578 pounds were paid out. Years later, Hathorne’s grandson, disgusted with what his grandfather had done and wishing to distance himself from him, inserted a “w” into his name and is now remembered as the author Nathaniel Hawthorne.11

Apparently the horror of the trials had a salubrious effect. While cruel religious laws remained on the statute books, few were followed out to the letter.

In the early colonies religion was not only a vital part of people’s lives, but an infrangible aspect of their allegiance to their sovereign. William Penn, royal proprietor of the colony of Pennsylvania, put the matter clearly in 1682:

“When the great and wise God had made the world, of all his creatures it pleased him to chuse man his Deputy to rule it; and to fit him for so great a charge and trust, he did not only qualify him with skill and power, but with integrity to use them justly. This native goodness was equally his honour and his happiness; and whilst he stood there, all went well; there was no need of coercive or compulsive means, the precept of divine love and truth, in his bosom, was the guide and keeper of his innocency.”12

William Penn is known as a champion of religious liberty, but even he limited that liberty, writing, if there was a disobedient posterity that “would not live conformable to the holy law within,” and, as a result, they would fall “under the reproof and correction of the just law without, in a judicial administration.” Further on in the document he wrote: “So that government seems to me a part of religion itself, a thing sacred in its institution and end.” Article 35 declared “that all persons living in this province, who confess and acknowledge the one Almighty and eternal God, to be Creator, Upholder and Ruler of this world . . . shall, in no ways, be molested or prejudiced for their religious persuasion.” Thus, the liberties were narrowly defined.

William Penn’s authority was based on a charter given by King Charles II, and was in harmony with English common law.13 People “were by oath in law and conscience obligated to the monarch who was, of course, placed on his throne by God.”14 It is not surprising, then, that the English colonists who settled in America wrote, without exception, their state constitutions with English common law in mind. Allegiance to the governor was allegiance to the king, and allegiance to the king involved how they expressed their religious practices.

But that hitherto-inbred loyalty of American citizens to their liege lord rapidly withered on the vine. The Revenue Act of 1766, the Townshead taxes of 1767, the American Board of Customs, and the discovery of the Hillsborough letter in 1768 all helped them reassess their loyalty to the king. The final severance came when the so-called Olive Branch Petition, directed not to Parliament but to King George III himself, was contemptuously rejected. In an unpublished manuscript Benjamin Franklin expressed the matter clearly:

“Whereas, whenever kings, instead of protecting the lives and properties of their subjects, as is their bounden duty, do endeavor to perpetrate the destruction of either, they thereby cease to be kings, become tyrants, and dissolve all ties of allegiance between themselves and their people.”15

The men who assembled in Philadelphia to write a new constitution were lawyers and businessmen, not clergymen. In terms of separation of church and state this was no doubt fortunate. A short time after Washington was elected as president of the United States the First Amendment to the Constitution was voted. It read, in part, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Then the clergy began to make their voices heard. On October 27, 1789, the First Presbytery Eastward in Massachusetts and New Hampshire sent President Washington an address in which they complained that there was no “explicit acknowledgment of the only true God and Jesus Christ whom He has sent inserted somewhere in the Magna Charta of our country.”16

Four years later one of the periodic yellow fever plagues hit Philadelphia, and people were dying at the rate of about 100 per day. The clergy drew their own conclusion—God was angry with the nation.17 In New York City John Mitchell Mason (1770-1829), one of the greatest pulpit orators of his day, voiced his concern in a sermon entitled “Divine Judgments.” He magnified the “irreligious feature of the Constitution as one of the chief causes of the calamities of which he was speaking.”18

And so it went, the past informing the present and an underlie of intolerance and persecution. More to come in Part II!

1 In Robert V. Remini, Daniel Webster and His Time (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1997), p. 181.

2 George Bancroft’s History of the United States did not appear until 1834.

3 The American Republic: Primary Sources, ed. Bruce Fronen (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Ind., 2002), p. 15.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., paragraphs 94 and 95.

6 Ibid., p. 79.

7 Will Durant, The History of Civilization, Vol. VII, p. 190.

8 Primary Sources, p. 22, paragraph 96.

9 Colonial Origins of the American Constitution. A Documentary History, ed. Donald S. Lutz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1998), p. 100.

10 A. T. Jones, The Two Republics, Rome and the United States (Battle Creek, Mich.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1891), p. 654.

11 “John Hathorne,” Wikipedia.

12 Primary Sources, p. 23.

13 As so defined by Sir Edward Coke: The king was the “defender of the faith,” and his subjects swore “to be true and faithful to our sovereign lord and king and his heirs, and truth and faith shall bear of life and member and terrene honour, and you shall neither know or hear of any ill or damage intended unto him that you shall not defend.” See Law, Liberty and Parliament, Selected Essays on the Writings of Sir Edward Coke, ed. Allen D. Boyer (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2004), p. 92.

14 Ibid., p. 86.

15 Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin, An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002), p. 310.

16 Jones, pp. 699, 700.

17 Years later General Burnside drew the same conclusion because the Civil War was going badly for the Union, and he formed the National Reform Association with ministers from 11 different denominations.

18 Jones.

Article Author: Lyndon McDowell

Lyndon McDowell is an educator and minister of religion, living in Atlanta, Georgia.