Finding Common Cause

Asma T. Uddin November/December 2021Asma T. Uddin is an internationally renowned American-Muslim scholar, author, constitutional lawyer, and religious freedom advocate. As a lawyer, she has defended the religious freedom rights of Christians, Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims, Native Americans, and Jews. But with her 2019 book, When Islam Is Not a Religion, Ms. Uddin opened a national conversation about Christian perceptions of Islam, and the very real social and legal consequences of these attitudes.

Here, she explores a path forward toward healing the divide between Christians and Muslims in America.

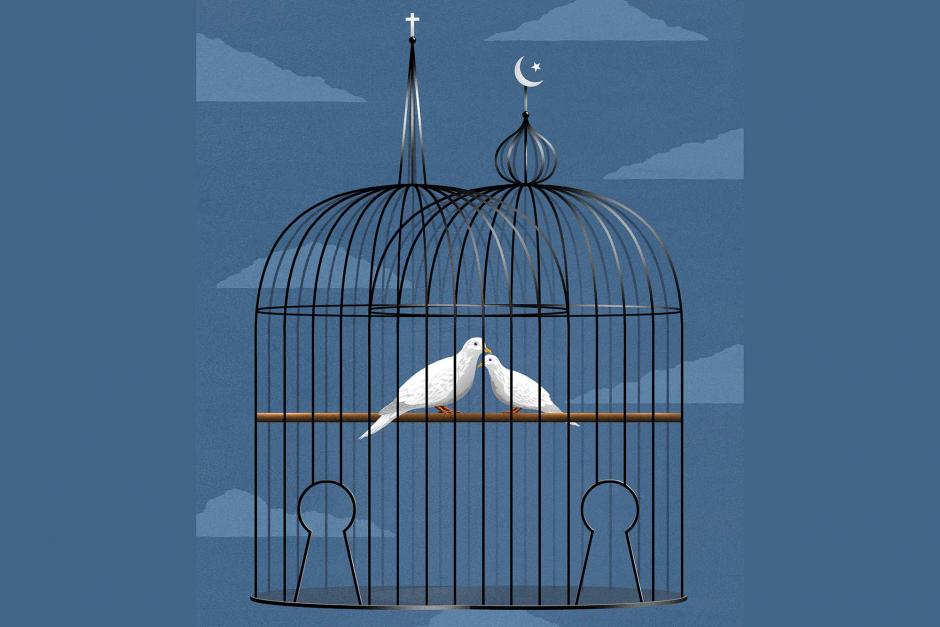

Illustration by Michael Glenwood

A Pew Research Center poll conducted in 2017 found that fully two thirds of white evangelicals in America believe Islam is not part of mainstream American society and that it encourages violence more than other faiths. Seventy-two percent of white evangelicals saw a natural conflict between Islam and democracy.1 According to a 2017 Baylor University survey, 52 percent of white evangelicals said that Muslims want to limit their freedom.2 And there are many other similar polls reflecting the same troubling divide between Muslims and evangelicals—with the latter group often reflecting an anti-Muslim antipathy that many other conservative Christians also feel.

For Americans interested in overcoming polarization broadly, and religious polarization specifically, the question arises: Is this divide bridgeable? If so, how?

In my recent book, The Politics of Vulnerability: How to Heal Muslim-Christian Relations in a Post-Christian America, I argue that religious freedom offers a viable path for bringing Christians and Muslims together. To understand how and why, however, it is important to first understand the nature of the conflict.

Understanding the Divide

Group Identity and Political Mega-Identities

Much of our understanding of group dynamics is based on a series of experiments conducted by social psychologist Henri Tajfel in the 1970s. Through a series of experiments, Tajfel found that people exhibit discriminatory intergroup behavior in a way that created the biggest gap between their group and the out-group. More than any other motivator, believing they were winning is what drove people’s behavior toward people outside their group.

Social scientists explain that this sort of group loyalty is core to who we are as humans.3 Group loyalty helps people avoid the strong psychological and physical effects of rejection. Studies have shown that we don’t just experience social isolation or stigma psychologically; these experiences also trigger a physical assault on our body.4 What this means in practice is that, even evolutionarily, humans are programmed to signal their allegiance to their tribe as a way of avoiding the loneliness and stress that comes with being cast out.

Our allegiance to our political tribes is no different. Elections can become pure team rivalry. Similar to Tajfel’s findings, other studies have found that in the election context, winning is what’s most important, and Americans are driven by what they oppose rather than what they support. For example, a 2016 Pew study found that “very unfavorable views” of the Democratic Party increased voting much more than a “deeper affection” for the Republican Party. Among Americans who are highly engaged in politics, this disparity became even starker—the more they hated the other side, the more likely they were to donate money to their own party.5 This may explain why politicians focus so much of their messaging on generating fear and hatred of the other party.

Intergroup Bias and Perceptions of Threat

Muslims and conservative Christians are in opposing groups and are parties unfortunately prone to severe intergroup bias. Studies show that in-group favoritism does not always result in out-group bias. That is, you can extend trust, cooperation, and empathy to your in-group, but not the out-group, and while this is a form of discrimination, it does not involve any sort of aggression or hostility toward the out-group.6

But tribalism in the religious context has been shown to result in out-group hostility. And there is evidence that Muslims, more than any other religious out-group, are the targets of this hostility. Perceptions of threat are part of the reason. Oxford political scientists Miles Hewstone, Mark Rubin, and Hazel Willis write: “The constraints normally in place, which limit intergroup bias to in-group favoritism, are lifted when out-groups are associated with stronger emotions.” Stronger emotions include things like feeling the out-group is moving against you: “an out-group seen as threatening may elicit fear and hostile actions.” Whereas “high status” groups (groups that are a numerical majority and have power) don’t feel threatened by minorities when the status gap is very wide, they are more likely to feel threatened when the status gap is closing.7 In the U.S. today, the Christian in-group does not feel the status gap is wide, and they have good reason to feel this way.

First, white preponderance is on the decline. In 1965 white Americans constituted 84 percent of the U.S. population and now Pew says white Americans will be a minority by 2055.8 In 1996 white Protestant Christians still made up two thirds of the population.9 Today they don’t even constitute a majority. What’s more, the decline of white Protestant America has brought with it a perceived end for some to the cultural and institutional world built primarily by white Protestants in the United States.

With this perceived end nearing, conservative white evangelicals feel besieged, and just as studies on intergroup bias predict, that vulnerability is being turned against the out-group. One aspect of this is revealed in surveys comparing perceptions of discrimination against Christians versus Muslims. In 2019 Pew found that Democrats and those who lean Democratic “are more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to say Muslims face at least some discrimination in the U.S. (92 percent versus 69 percent). . . . At the same time, Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say evangelicals face discrimination (70 percent versus 32 percent).”10 In 2017, the Rasmussen Report11 and PRRI found very similar discrepancies.12

Religious Freedom and Religious Polarization

Unfortunately, the hostility goes beyond merely dismissing anti-Muslim discrimination to outright hostility, and even attempts at limiting Muslims’ religious rights. At a time when religious freedom is often utilized to protect Christian interests in the U.S., some Christians use it to also exclude Muslims from the American fabric. I documented this in detail in my 2019 book, When Islam Is Not a Religion: Inside America’s Fight for Religious Freedom. There I explained how some conservative Christians deny the religious character of Islam in order to strip Muslims of religious freedom—including, for example, the right to build houses of worship, utilize religious arbitration to settle personal disputes, wear religious garb, and so on.

Political scientists Daniel Bennett and Logan Strother explored this phenomenon in their work. In one study, respondents were told that the government had blocked a house of worship.13 The house of worship was first described generically, then described as an evangelical church, and in the third scenario it was a mosque. When Bennett and Strother compared how respondents felt about protecting the house of worship, they learned that if you liked Muslims more than evangelicals, you were more interested in protecting the mosque. On the flipside, only 40 percent of respondents who felt more warmly toward evangelicals wanted to help the mosque.

In another study, political scientist Andrew Lewis looked at how conservatives and liberals respond to religious liberty claims differently depending on how the information is presented to them. First, respondents read about Muslim truck drivers who had to choose between transporting alcohol in violation of their religious beliefs or losing their jobs. Respondents then learned that either a well-known liberal or conservative law firm was representing the truck drivers in court.14

Lewis found that Democratic respondents were more supportive of the religious freedom claims when they were told a liberal law firm represented the drivers. They were also more likely to support conservative Christian claims after they were exposed to religious freedom claims by Muslims. As for conservative respondents, they were less likely to shift attitudes in support of Muslims, but were marginally more likely to support them if a conservative law firm was defending the Muslim claimants versus, say, the unambiguously liberal ACLU.

This second study reveals that the animosity Christians feel toward Muslims has to do with Muslims being both religious and political outsiders. As I demonstrate with reams of studies in The Politics of Vulnerability, many conservative Christians conflate Muslims—and specifically, advocacy for Muslims’ rights—with the political Left. This further entrenches the divide.

A Strategy for Healing

Understanding the social psychology involved in the Christian-Muslim divide makes clear that healing requires disrupting the mechanisms of out-group hostility. Out-group hostility results when the in-group feels threatened. As such, to counteract that hostility, strategies for healing must focus principally on reducing perceptions of threat.

Religious freedom is most pertinent to the method called “superordinate goals.” Creating “superordinate goals” is a social science approach to reducing prejudice. The theory was first tested by husband-and-wife team Muzafer and Carolyn Wood Sherif, both of them social psychologists, when they brought a group of boys to a camp where they were split into two groups that would compete with each other at first (producing “intragroup solidarity” and “intergroup rivalry”) and then given a common goal to increase intergroup solidarity.

In our hyperpartisan context, superordinate goals can be hard to identify. Shared goals require some level of trust in authorities; people want to know that the people in charge are working in their interest. Political scientists have found that it is becoming increasingly difficult to find a cross-cutting issue that unifies Democrats and Republicans over and above the partisan rancor.

But religious freedom might be the cross-cutting issue we need. Recall Lewis’ findings that “priming” liberals with Muslims’ religious claims made them less opposed to evangelicals’ claims. “Liberals are essentially saying, ‘Oh, I hadn’t thought about that in this context. It’s not just about the Christians; now it applies to all groups,’ ” Lewis explained to me. In other words, liberals who are dedicated to protecting vulnerable minorities begin to understand that the goal is unachievable if evangelicals are not protected too. The implication for conservatives is that if they want liberals to support them, conservatives need to increase their own support for Muslims’ religious freedom.

Religious freedom is uniquely positioned as a viable superordinate goal because it ensures that groups are not made to feel as though their identity is being threatened or minimized. It allows people to hold on to their distinctiveness even as they let go of their prejudices.15 Religious liberty for all does not erase differences, but instead helps Americans live among and with diversity.

1 Emma Green. “How Much Discrimination Do Muslims Face in America?” The Atlantic, July 26, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/07/american-muslims-trump/534879/.

2 Julie Zauzmer and Michelle Boorstein, “Evangelicals Fear Muslims; Atheists Fear Christians: New Poll Shows How Americans Mistrust One Another,” Washington Post, September 7, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/acts-of-faith/wp/2017/09/07/evangelicals-fear-muslims-atheists-fear-christians-how-americans-mistrust-each-other/.

3 “Social Identity Theory,” Simply Psychology, 2019.

4 Lilliana Mason, “Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity” (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), p. 139.

5 Pew Research Center, “Partisanship and Political Animosity in 2016,” June 22, 2016.

6 Miles Hewstone, Mark Rubin, and Hazel Willis, “Intergroup Bias,” Annual Review of Psychology 53, no. 1 (2002): 575-604.

7 Ibid.

8 Pew Research Center, “Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065,” September 28, 2015.

9 Pew Research Forum, “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace,” October 17, 2019.

10 Pew Research Center, “Many Americans See Religious Discrimination in U.S.—Especially Against Muslims,” May 17, 2019.

11 Rasmussen Reports, “Democrats Think Muslims Worse Off Here Than Christians Are in Muslim World,” February 7, 2017.

12 Public Religion Research Institution, “Majority of Americans Oppose Transgender Bathroom Restrictions,” March 10, 2017.

13 Daniel Bennett and Logan Strother, “Which Groups Deserve Religious Freedom Rights? It Depends on What You Think of the Groups,” Religion in Public, January 3, 2019.

14 Kelsey Dallas, “On National Religious Freedom Day, Consider the Double Standard on Religious Freedom—and Why It’s a Problem,” Deseret News, January 16, 2019.