Fuel or Immunity?

Tobias Cremer November/December 2022A surprising take on the dynamics between religion and right-wing populism

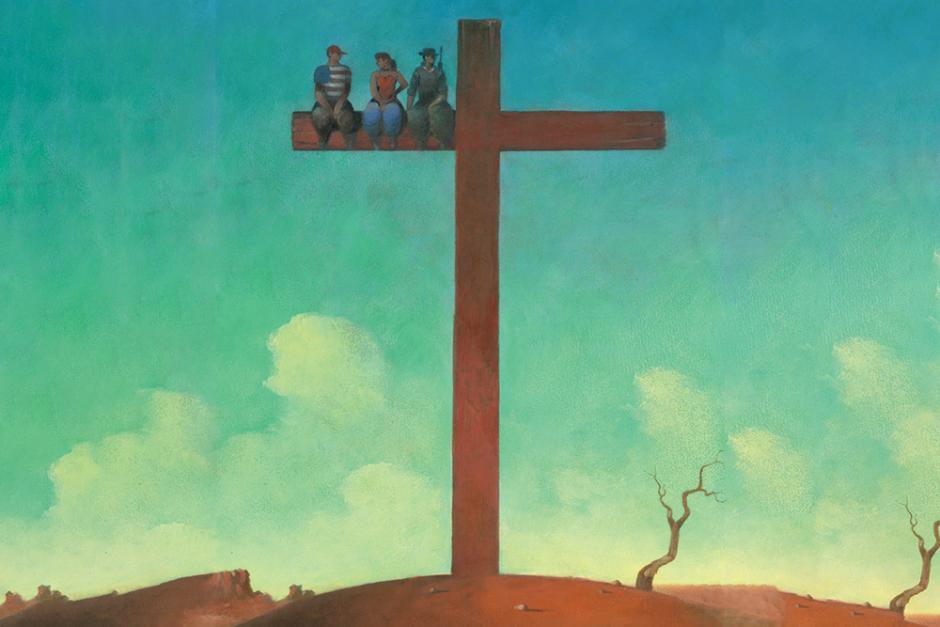

Illustrations by Brad Holland

Is religion a fuel for, or a barrier against, the rise of right-wing populist politics in the West? This question is preoccupying faith leaders, politicians, and commentators alike on both sides of the Atlantic as right-wing populists make conspicuous use of Christian language and symbols.

In Germany, for example, the anti-Islamist Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the West (PEGIDA) paraded oversized crosses in Germany’s national colors at their demonstrations. Another right-wing populist group, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), inserted a defense of Germany’s Judeo-Christian heritage into its party manifesto.

In France the Rassemblement National (RN) challenged the rules of laïcité—the foundational French principle of secular governance—by pushing for Nativity scenes in public spaces. At the same time, far-right firebrand Éric Zemmour proclaimed that Catholicism has a “birth right” to cultural hegemony in France.

Meanwhile, in the United States, President Trump styled himself as the defender of Christian America by posing with a Bible in his hand in front of St. John’s Church in Washington, DC, and some of his supporters paraded oversized crosses and Jesus flags during the storming of the U.S. Capitol in January 2021.

Given the centrality of Christian symbolism in right-wing populist rhetoric, many observers have assumed close ties between conservative Christianity and the populist right.1 However, several studies, focusing on the motives, strategies, and policies of right-wing populist leaders and movements, have argued otherwise. They contend that when right-wing populists make reference to Christianity, it primarily reflects a culturalized but largely secular “civilizationism.” Thus, right-wing populists “hijack” Christianity to serve as an exclusivist identity-marker against Islam without necessarily embracing Christianity as a faith.2

For instance, in spite of its prominent references to Christianity, the AfD has been shown to be one of Germany’s most secular parties in terms of its leadership and membership.3 It has openly attacked German churches that have welcomed refugees, demanded the abolition of church privileges in taxation or education, and pushed for an overhaul of Germany’s church-friendly constitutional settlement of “benevolent neutrality.”4

Similarly, in France the RN has remained absent from the Catholic grassroots demonstrations against same-sex marriage, while styling itself as the main champion of a strictly secularist reading of laïcité and defender of women and LGBTQ rights against conservative religion.5

Even in the United States, where the Trump administration sought to balance clashes with America’s churches on immigration and race relations by catering to the Christian right on social issues, observers have argued that Trumpism has been primarily driven by the rise of a “post-Christian right,” which is less socially conservative but more radical in its opposition to immigration, Islam, and racial equality.6

Given this apparent tension between right-wing populists’ religion-laden rhetoric and some of their seemingly less Christian policy positions, the question arises as to how these parties’ politics are perceived by Christian communities themselves.

Religious Vaccination?

At first glance, a review of election results, survey data, and existing quantitative studies suggests a high degree of variation in the responses of Christian communities to right-wing populist politics across Western countries. In the US, Christians—and White Evangelicals in particular—are among Donald Trump’s most loyal supporters: more than 80 percent of White Evangelicals and strong majorities of White Catholics and other Protestants voted for Trump in 2016 and 2020, leading observers to interpret Trumpism as the latest expression of America’s tradition of White Christian nationalism.7

In Western Europe, however, scholars have identified a “religion gap” or “religious vaccination effect” among Christian voters against voting for right-wing populists.8 In Germany, for instance, the AfD has consistently performed almost twice as well among irreligious voters as among Catholics and Protestants. In France the FN/RN has traditionally performed significantly worse among churchgoing Catholics compared to other parts of the population. In the 2012 presidential election, for instance, only 4 percent of practicing Catholics chose right-wing populist candidate Marine Le Pen, compared to 18 percent of the general population.9 Similar trends have been observed in other European countries, ranging from Denmark to Italy, Austria to Portugal.

On the surface there is a high level of variation in electoral outcomes between Christians in Western Europe and Christians in America. Yet a closer inspection of attitudes and sociodemographic backgrounds reveals a more uniform development underneath: namely, a growing schism between the traditional religious right and a new secular right. For instance, the 2016 GOP primary results showed that Donald Trump’s earliest and most solid supporters were not the most pious. Rather, they were religiously unaffiliated voters, among whom he performed almost twice as well as among frequent churchgoers (57 percent versus 29 percent).10

This observation is symptomatic of a schism in the Republican electorate, as America’s Christian congregations are becoming more global in outlook and racially diverse in their membership. At the same time, Donald Trump’s core base of working-class White people has undergone a process of rapid secularization in recent years.11 The latter process has led to the emergence of a growing number of nonpracticing “cultural Evangelicals.” who might culturally identify as “Christian” or “Evangelical,” but who are increasingly dissociated from churches, congregations, and evangelical beliefs.12 Like their European counterparts, these nonpracticing “cultural Christians” often prove more sympathetic toward right-wing populist positions and candidates than their churchgoing brethren.13

American political commentator Peter Beinart has suggested a reason for this: “When cultural conservatives disengage from organized religion, they tend to redraw the boundaries of identity, deemphasizing morality and religion and emphasising race and nation.”14

But why, then, did American Christians diverge so strongly from their European brethren in their support for the populist right? Why did they embrace Donald Trump after the GOP primaries, whereas churchgoing Europeans continued to vote for far-right parties at much lower levels?

(A Lack of) Christian Alternatives

One key factor in this context is the political competition faced by right-wing populists’ and especially the role of conservative and Christian democratic parties. The underlying logic here is that religious immunity against populism is indirect. It rests on the mechanism that, in countries with strong Christian democratic parties, Christian voters are simply “not ‘available’ to these [right-wing populist] parties, because they are still firmly attached to Christian Democratic or conservative parties.”15

In the case of Germany, for instance, the powerful Christian Democratic party (the CDU/CSU) has ownership over key Christian issues and provides a political home for Christian voters. This, scholars have argued, is a key explanatory variable for the strength of the religious immunization effect against the populist right.16

Similarly in France, the center-right Les Républicains (LR) has for many decades provided French Catholics with a fixed political home. Initially, the 2017 presidential election seemed to confirm this rule. In the first round of voting, 46 percent of practicing Catholics and 55 percent of the most frequent churchgoers cast their vote for the LR candidate François Fillon, compared to only 20.1 percent of the general population.17

While this support demonstrated French Catholics’ continued attachment to the center right, however, it also epitomized a new dilemma for Catholics. The Catholic turnout was insufficient to enable Fillon in 2017 (or his successor, Valérie Pécresse, in 2022) to enter the second round of the presidential elections. Thus, Catholics were left with the choice between Emmanuel Macron’s socially liberal LREM and Marine Le Pen’s right-wing populist RN.

Given Macron’s party’s embrace of liberal positions on social issues such as embryo research, assisted suicide, surrogacy, and assisted reproductive technology for same-sex couples, this boiled down to what one Catholic commentator called a choice between the “chaos” of the RN and the “decay” of Emmanuel Macron’s socially liberal agenda.18 As result, in both the 2017 and 2022 runoffs, religious immunity markedly eroded as politically “homeless” Catholics voted for Marine Le Pen’s RN at similar or even higher rates than their secular neighbors.

Party loyalty and a perceived lack of alternatives also emerged as key factors in shaping Donald Trump’s ability to attract many initially sceptical Christian voters in the US—albeit in different ways. For one, American faith voters have a long-standing attachment to “God’s Own Party.” Thus, rather than strengthening faith-based inhibitions against right-wing populism by binding Christians to a competitor party, this helps explain why many Christians voted for Trump during the general election even if they had opposed him during the primaries.

Indeed, White Evangelicals were the most likely group to say that they supported Trump mainly because he was the Republican nominee (38 percent of them gave this reason, compared to 28 percent of GOP voters in general and 13 percent of irreligious Trump supporters).19

Perhaps even more important than Christians’ loyalty to the Republican Party (positive partisanship), however, was apparently their rejection of the Democratic alternative (negative partisanship). Pew Research found, for instance, that among Catholic, Evangelical, and mainline Protestant Trump voters, Trump’s single most attractive feature was that “he is not Hillary Clinton,” with 76 percent of White Evangelicals citing this as a “major reason” for supporting Trump in 2016.20

Faith Leaders and the Social Firewall

Yet the lack of party alternatives alone cannot fully account for the ability of right-wing populists to co-opt religion for political gain. Instead, a second important yet often overlooked factor is the role of faith leaders and institutional churches. Their willingness and ability either to condone and legitimize or to challenge and socially taboo the religious references of right-wing populists appears to correlate directly with the strength of religious immunity.21

Scholars have long emphasized the importance of social taboos established by elite actors in determining social and political behavior in general, and in voters’ reaction to right-wing populist movements in particular.22 Mainstream parties or the media are, for instance, central actors in establishing social taboos around right-wing populists through a cordon sanitaire of noncooperation or non-reporting.

Church leaders may play a similar role within congregations through public statements, sermons, and social-norm setting. In Germany, for example, the churches’ consistent and unambiguous public opposition to the AfD has often been credited with creating a strong “social firewall’ in religious communities against the populist right.23 Both the Protestant and Catholic church leadership condemned AfD rhetoric as “hate speech,”24 declared the positions of the AfD leadership to “stand in profound contradiction to the Christian faith,” and spoke out in favor of welcoming refugees.25 Given this clear public demarcation, disaffection to the AfD has become associated with significant social costs among church members.

For decades France’s Catholic Church was no less pronounced in its public opposition to the FN/RN. Its repeated interventions included warning Catholics that the FN’s positions were “incompatible with the gospel and the teaching of the church” (Cardinal Decourtray), individual clergy denying FN politicians the holy sacraments, and ubiquitous sermons against the FN. The institutional church appeared committed to maintaining a strong social taboo against support for the FN. According to some scholars, this led to an “institution effect” and a “Pope Francis effect,” and thus whenever church authorities publicly spoke out in favor of immigration or against the populist right, sympathies with the latter decreased among practicing Catholics in France.26

In the second round of the 2017 and 2022 presidential elections, however, Catholic authorities ceased to make use of this authority. Unlike in previous elections and in contrast to their Protestant, Muslim, and Jewish colleagues, in 2017 and 2022 the Catholic hierarchy gave no voting instructions against the FN/RN, but referred voters to “their own discernment.”

The reasons for this silence were linked primarily to a broader retreat of France’s episcopate from public life in the wake of sexual abuse scandals. The consequences, however, were highly political, undermining the social taboo around the RN by discouraging clergy from using their authority to criticize the RN. This further separated religion from politics, and thereby implicitly undermined the church’s moral authority in political issues in general.

In the long run, some Catholic leaders publicly cautioned that such developments may contribute to a situation in France, similar to that in the US, where the inability or unwillingness of US faith leaders to create a social taboo around Trumpism appears to be a key variable in understanding the lack of religious immunity there.

As in France, the comparative lack of social taboos around right-wing populism in the US is not necessarily a result of the faith leaders’ affinity with Trumpism. On the contrary, my own research as well as data from the National Association of Evangelicals has shown that most of their leaders were initially highly critical of Trumpism. Similarly, senior representatives of American Catholicism and mainline Protestantism have repeatedly and publicly condemned Trump’s politics.

In trying to understand why faith leaders’ scepticism did not translate into the same social taboo among their flock as had been the case in Europe, two factors are particularly important. First, the decentralized structure of the American religious landscape limited Christian leaders’ ability to “speak for Christianity” publicly. America’s religion-friendly separation of church and state has created a religious marketplace full of diversity and vitality. Yet the same diversity also means that no single set of leaders can speak with the level of authority for American Christianity, as, for instance, an alliance of Protestant and Catholic Bishops could in Germany or France. Such dynamics are exacerbated by an accelerating crisis of religious hierarchies and shift toward non-denominational churches in America in recent decades.27

A second key factor amplified these structural limitations to American faith leaders’ ability to be heard; that is, a reported lack of willingness to speak out against Trumpism. Indeed, surveys show that half of American pastors felt limited in their ability to speak out on moral and social issues, and that only one in five (21 percent) felt comfortable speaking out about specific political actors.28

In my conversations with faith leaders, many of them confirmed that Trumpism was a particularly delicate topic. Many conservative pastors who were alarmed about Trump said they did not dare speak out because of fear of running into conflict with congregants or donors.

As a result, the silence of American faith leaders emerges as a crucial factor in accelerating many American Christians’ “conversion” to the populist right, whereas the outspoken opposition of German and French faith leaders had a significant impact in bolstering Western European Christians’ religious immunity to right-wing populism.

Future in the Balance

These findings—about the potential for religious immunity against the far right, as well as its dependence on the behavior of political and religious elites—are significant. They are important not least because they challenge traditional assumptions about the nexus between conservative Christianity and the populist right.

Thus, right-wing populism is not merely a revival of America’s old religious right and its expansion to Europe. It appears, instead, to be linked to the processes of secularization and the resulting rise of a new post-religious right in Western Europe and America. This new post-religious right is distinct from Christian beliefs and institutions and is often politically, culturally, and sociodemographically opposed to them as well.

Whether or not the old religious right and the new secular right might clash or cooperate will depend on the behavior of faith leaders and political elites. Far from being helpless bystanders, these actors play an outsized role as the populist wave breaks over the West. They will help shape not only the electoral fortunes of right-wing populists but also what role religion will come to play in Western societies going forward.

1 Andrea Althoff, “Right-Wing Populism and Religion in Germany: Conservative Christians and the Alternative for Germany (AfD),” Zeitschrift für Religion, Gesellschaft und Politik 2, no. 2 (2018): 335-363; Philip S. Gorski and Samuel L. Perry, The Flag and the Cross (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022); Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry, Taking America Back for God (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

2 Rogers Brubaker, “Between Nationalism and Civilizationism: The European Populist Moment in Comparative Perspective,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40, no. 8 (2017): 1191-1226; Nadia Marzouki, Duncan McDonnell, Olivier Roy, Saving the People: How Populists Hijack Religion (London: Hurst, 2016).

3 David Elcott et al., Faith, Nationalism, and the Future of Liberal Democracy (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 2021).

4 Tobias Cremer, “A Religious Vaccination? How Christian Communities React to Right-Wing Populism in Germany, France and the US,” Government and Opposition, (2021): 1-21.

5 Dimitri Almeida, “Exclusionary Secularism: The Front National and the Reinvention of laïcité, ” Modern & Contemporary France 25, no. 3 (2013): 249-263; Marzouki, McDonnell, Roy.

6 Eric Kaufmann, Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities, (London: Penguin, 2018); Timothy Carney, Alienated America: Why Some Places Thrive While Others Collapse (New York: HarperCollins, 2019).

7 Gorski and Perry, op cit; Whitehead and Perry, op cit.

8 Tim Immerzeel, Eva Jaspers, and Marcel Lubbers, “Religion as Catalyst or Restraint of Radical Right Voting?” West European Politics 36, no. 5 (2013): 946-968; Pascal Siegers and Alexander Jedinger, “Religious Immunity to Populism: Christian Religiosity and Public Support for the Alternative for Germany, ” German Politics 30, no. 2 (2021): 149-169; Cremer 2021a.

9 P. Siegers and A. Jedinger, “Religious immunity to populism: Christian religiosity and public support for the alternative for Germany,” German Politics 30, no. 2 (2021): 149–169.

10 Carney, Alienated America, p. 121.

11 W. Bradford Wilcox et al., “No Money, No Honey, No Church: The Deinstitutionalization of Religious Life among the White Working Class,” Research in the Sociology of Work 23 (2012): 227-250; Carney.

12 Ryan P. Burge, “So Why Is Evangelicalism Not Declining? Because Non-Attenders Are Taking On the Label,” Dec. 10, 2020, religioninpublic.blog.

13 Emily Ekins, “The Liberalism of the Religious Right: Conservatives Who Attend Church Have More Moderate Views Than Secular Conservatives on Issues Like Race, Immigration, and Identity,” Sept. 19, 2018, Cato.org.

14 Peter Beinart, “Breaking Faith,” The Atlantic, April 2017.

15 Kai Arzheimer and Elisabeth Carter, “Christian Religiosity and Voting for West European Radical Right Parties,” West European Politics 32, no. 5 (2009): 985-1011.

16 Siegers and Jedinger.

17 French Institute of Public Opinion (2017).

18 Samuel Pruvot, Les Candidats à confesse (Monaco: Editions du Rocher, 2017).

19 Gregory A. Smith, and Jessica Martinez, “How the Faithful Voted: A Preliminary 2016 Analysis,” FactTank Newsletter, Pew Research Center, Nov. 9, 2016.

20 Ibid.

21 Tobias Cremer, “Nations under God: How Church–State Relations Shape Christian Responses to Right-Wing Populism in Germany and the United States,” Religions 12, no. 4 (2021): 254.

22 Léonie de Jonge, “The Populist Radical Right and the Media in the Benelux: Friend or Foe?” International Journal of Press/Politics, Dec. 29, 2018; Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (New York: Vintage, 2012).

23 Andreas Püttmann, “AfD und Kirche: Abgrenzen statt annähern,” Die Zeit, May 24, 2016; Cremer 2021b.

24 Deutsche Bischofskonferenz, “Bischöfe: AfD nicht mit christlichem Glauben vereinbar,” Deutsche Bischofskonferenz (2016), www.dbk.de.

25 “Bedford-Strohm: AfD-Spitze im ‘Widerspruch zum christlichen Glauben,’ ” (2016), www.Evangelisch.de.

26 Vincent Geisser, “L’Église et les catholiques de France face à la question migratoire: le grand malentendu?” Migrations Societe 3 (2018): 3-13.

27 Mark Chaves, American Religion: Contemporary Trends (Princeton. NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011); David E. Campbell and Robert D. Putnam, “America’s Grace: How a Tolerant Nation Bridges Its Religious Divides,” Political Science Quarterly 126, no. 4 (2011): 611-640.

28 Barna Group, Faith Leadership in a Divided Culture (Ventura, CA: Barna, 2019).

Article Author: Tobias Cremer

Tobias Cremer is a junior research fellow at Pembroke College, Oxford, United Kingdom. He holds a PhD in Politics and International Relations from the University of Cambridge, an MPP from the Harvard Kennedy School, an MPhil in Politics and International Studies from Cambridge University, and a BA in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics from Sciences Po (The Paris Institute of Political Studies). His research focuses on the relationship between religion, secularization, and the rise of right-wing identity politics throughout western societies. You can follow him on Twitter, @cremer_tobias.