Go, Girl, Go!

Clifford R. Goldstein May/June 2020Besides her brains, charisma, and speaking ability, one of the things that gave Anne Hutchinson such a faithful following in seventeenth-century Puritan Boston was her medical knowledge. At a time when the following remedy—“Take the milk of a nurse that gives suck to a male child and also take a he-cat and cut off one of its ears or a piece of it and let it bleed into the milk and then let the sick woman take drink of it”—was commonly prescribed for ailing females, it’s no wonder that Anne Hutchinson’s skillful use of herbal and natural remedies made her loved and accepted by many.

Her midwifery skills, as well, added to her popularity, especially when one of the tonics for a woman in a difficult childbirth was: “Take a lock of a virgin’s hair on any part of the head, of half the age of the woman in travail. Cut it very small to fine powder. Then take twelve ants’ eggs dried in an oven . . . and make them into powder with the hair. Give this with a quarter of a pint of milk from a red cow; or for want of it give in it strong ale wort.” In contrast to such quackery, a talented midwife like Anne, who learned the trade in London, was greatly appreciated.

But not appreciated by everyone: some religious leaders in seventeenth-century Boston, for numerous reasons, believed her a threat and used whatever they could to undermine her. That included accusation made after an unfortunate delivery that the talented midwife had been involved in.

When Mary Dyer, the milliner’s wife, already worn and beaten down by three pregnancies in four years, faced a very difficult birth in October of 1637, Anne Hutchinson was summoned to help. The fetus—positioned upside down, breeched hipwise, with the buttocks, not the head, coming out first—was, finally, delivered, but deformed and dead. The little girl was so grossly malformed that they didn’t want to present her to the still-unconscious mother.

After counselling with a trusted cleric who advised that they secretly bury the infant (if this had happened to his wife, he said, he “would have desired to have it concealed”), Anne and some others did just that, according to a custom and law in England, which dictated: “If any child be dead born, you yourself shall see it buried in such secret place as neither hog nor dog, nor any beast may come unto it, and in such short [time] done, as it may not be found or perceived, as much as you may.”

A year later, however, adding to Anne’s woes (she had already been convicted for a host of “offenses”), the story came out about the stillbirth and secret burial, and an investigation ensued. This inquiry included exhuming the fetus, depicted as having “a face, but no head, and the ears stood upon the shoulders and were like an ape’s; it had no forehead, but over the eyes four horns, hard and sharp . . . it had two mouths and in each of them a piece of red flesh sticking out.” It was described as a “monster,” and this dead baby was linked, warned Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop, to the “monstrous errors” of Anne Hutchinson, all the more reason for banishing this “liar,” “instrument of the devil,” and “proud dame.”

Such was the environment in which one of early America’s religious figures, and symbol of the dangers of intolerance, Anne Hutchinson, faced. Who was this woman, and what can we, heirs of land on which she suffered for her beliefs, learn from this story about the separation of church and state?

Away From the Anglican Papists

Anne Marbury was born in Alford, England, in 1591, to a father who, having more than once challenged the ecclesiastical status quo of the Anglican Church, found himself more than once imprisoned as well, even before Anne had been born.Thus, one could say that Anne got her willingness to challenge authority honestly.

She grew up in an England in which challenging authority, especially religious authority—all but inseparable from political authority—was the rage.Hence, you didn’t need Aristotelian logic to see where such challenges would lead, especially in a land in which religious nonconformity could get you tortured, burned at the stake, or beheaded.Though King Henry VIII had broken with Rome in 1533-1534, essentially forming the Anglican Church, for many English the break didn’t so far enough, and they feared that the “Anglican papists” were dragging them back to Rome.What galled them, among other things, were the continuation of “popish rituals” in the church, such as kneeling in Communion, wearing of copes and surplices, the use of organs, etc. Hence a great deal of the turmoil, violence, and intolerance that wracked England could be traced, at least partially (the Catholic-Protestant divide brought plenty of its own blood and suffering as well), to the Puritans (originally a term of abuse), who found themselves facing politically powerful clerics who didn’t appreciate these fanatics (and some were) and the trouble that they were causing the Church of England.

Against such a background, Anne (now Hutchinson, having married a wealthy sheep farmer and textile merchant, William Hutchinson) found herself more and more at odds with the established church, having already caused a bit of a stir by leading out in religious meetings in her home. Having aligned themselves with nonconformist Protestants, the Hutchinsons faced the difficult choice of toughing it out in an England that was becoming increasingly hostile,

or following others of their Puritan ilk across the Atlantic to the new world.Finally, after the birth of their fourteenth child, Anne and her husband, offspring in tow, sailed for Boston in 1634, heading to the new Promised Land.

Anne in the Puritan America

The way most schoolchildren in America had been taught the story, one could think that the Pilgrims were left-wing freedom-loving progressives who fled the repressive intolerance of Stuart England in order to create a liberal democracy in a new world, where all faiths could live together in mutual respect, regardless of their beliefs, creeds, and (to the degree possible) practices. Though the Pilgrims did leave England because of persecution, the New England that they created was, in terms of religious freedom, not much better than the Old England that they left. The Puritans, once the persecuted, now became the persecutors, and in Anne Hutchinson they found plenty to persecute.

Besides being a fairly aggressive lay religious leader at a time when women were banned from taking part in church service or even from speaking in churches, Anne also led out in meetings in her own home, a fairly common practice as long as only women attended (that is, women could teach women but not men). Yet word got out that not only were men attending these meetings, but that this upstart woman had been challenging the theology of the local church as well.

“The crisis deepened in 1636,” wrote law professor Douglas Linder, “when Hutchinson, upset with a sermon being delivered by John Wilson, a minister hand-picked by Governor Winthrop to replace a minister favored by Anne, stood up and walked out of the meetinghouse. A number of other women followed her out.”

A former mentor, John Cotton, needing to distance himself from Anne Hutchinson, described her weekly Sunday meeting as a “promiscuous and filthie coming together of men and women without Distinction of Relation of Marriage” and continued, “Your opinions frett like a Gangrene and spread like a Leprosie, and will eate out the very Bowells of Religion.”

Her theological opinions, which would “eate out the very Bowells of Religion,” were, interestingly enough, somewhat similar to what the apostle Paul had faced more 1,500 years before, and also what had started the Protestant Reformation itself. And that was the tension, still debated within Christendom today, between faith and works. Anne believed that God predestined those who were saved to be saved and those who were lost to be lost, period, and thus the saved had no need of works because it was all of God’s grace. This is, essentially, a Calvinist position still believed by many today.In contrast, the local establishment, though thoroughly Protestant, nevertheless believed that good works were an essential part of faith and that her theology would lead to indolence, to sin, and to the undoing of the unity and prosperity of the colony.

Added to this was her less-than-strict adherence to the Puritan Sunday regulations, as well as the idea that people could be taught by the Holy Spirit apart from the biblical text or outward rules and regulations; which, again, sent a shiver down the spine of the authorities, which feared where their views could lead.Anne’s wealth, charisma, medical skills, biblical knowledge, and sheer intelligence gained her enough of a following that, eventually, she had to be dealt with.

“Nor Fitting for Your Sex”

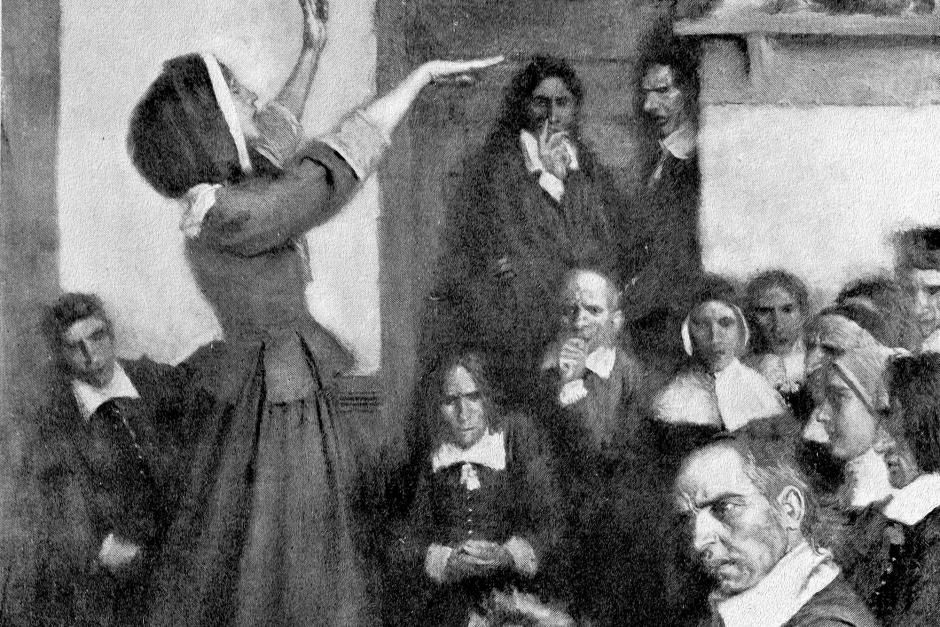

On November 7, 1637, Anne Hutchinson, accused of heresy, was brought to trial in a thatched meetinghouse in Cambridge, where the following charges were read against her: “Mistress Hutchinson, you are called here as one of those that have troubled the peace of the commonwealth and the churches here. You are known to be a woman that hath had a great share in the promoting and divulging of those opinions that are causes of this trouble. . . . You have spoken divers things, as we have been informed, very prejudicial to the honour of the churches and ministers thereof. And you have maintained a meeting and an assembly in your house that hath been condemned by the general assembly as a thing not tolerable nor comely in the sight of God nor fitting for your sex.” At total of 86 charges were brought against her before a court of about 40 men.

The outcome was never in doubt, Anne having greatly riled the powers-that-be over religious teaching in a new world that, closely tied to the old, knew nothing of religious freedom or separation of church and state.Though pregnant with her fifteenth child (which she eventually lost), Anne Hutchinson was found guilty, and the sentence was banishment, not a trivial punishment in the harsh primitive environment of early-seventeenth-century America (you weren’t put on the first plane out of there).In 1638 Anne, along with her family and 60 followers, moved first to Rhode Island and then, later, New York, where, in 1653, she and five of her children were massacred by Indians determined to rid their land of foreign occupiers.

The Legacy of Anne Hutchinson

Though hardly a household name, Anne Hutchinson should serve as a stark reminder of, however much people can believe passionately, even fervently in their own religious beliefs, the right to those beliefs remains sacred, so sacred that no government should be allowed to punish anyone on account of those beliefs. This is the essence of church-state separation, and most Americans today take this notion for granted because it has been part and parcel of the American experiment for most of this nation’s existence.It’s hard to imagine anyone in the United States being tried in a legal courtroom over the orthodoxy of their religious beliefs.

But it happened, even on this continent, and though long ago, it wasn’t, in terms of human history, that long ago.(The Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris was already more than 300 years old about the time Anne got the boot.) The propensity to persecute those who challenge the status quo, who think differently, who don’t conform, is always present and, hence, must always be kept in check.

In 1922 a statue of Anne Hutchinson was erected on the grounds of the Massachusetts State House. In 1987 Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis pardoned Anne, revoking her banishment, though 350 years too late.

And though hardly either the advocate for women’s rights and for religious liberty that she is often remembered for, Anne Hutchinson should stand as a constant reminder of why this country has separated church and state, and why it needs to keep them that way, too.

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.