Intelligent Reasoning

Holly Hollman May/June 2006

The Latest Controversy_—Defining ID

"Intelligent design," or "ID" as it is often called, is a theory that holds that certain features of the natural world are best explained by an intelligent cause, as opposed to natural selection. Its proponents say that the complexity of living organisms indicates the work of a designer. Generally, they do not name the designer and disavow any interest in defending a creationist belief based upon Genesis. On the surface, ID appears to be unrelated to efforts to promote biblical creationism. While the ID movement has mostly been focused on research and writings of private-interest groups such as the Discovery Institute, in Seattle, Washington, there has been a growing interest in ID from public school boards. The nature of that interest, however, may be changing following recent events in Dover, where the ID movement experienced its first legal test, and failed.

Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District

The Dover case began with the adoption of a poorly written school board policy providing that "students will be made aware of gaps/problems in Darwin's theory and of other theories of evolution including, but not limited to, intelligent design." The school district issued a press release, explaining its policy to treat intelligent design as a bona fide scientific theory competing with the scientific theory of evolution. The release included this statement, to be read to all students prior to the teaching of the scientific theory of evolution: "The state standards require students to learn about Darwin's Theory of Evolution and to eventually take a standardized test of which evolution is a part. Because Darwin's Theory is a theory, it is still being tested as new evidence is discovered. The Theory is not a fact. Gaps in the Theory exist for which there is no evidence. A theory is defined as a well-tested explanation that unifies a broad range of observations. Intelligent design is an explanation of the origin of life that differs from Darwin's view. The reference book Of Pandas and People is available for students to see if they would like to explore this view in an effort to gain an understanding of what intelligent design actually involves. As is true with any theory, students are encouraged to keep an open mind."

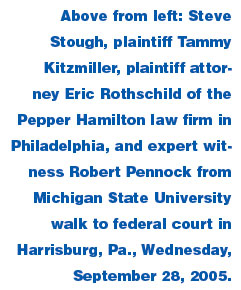

The adoption of the policy by the school board set off an immediate controversy. Dover science teachers refused to read the statement, forcing school administrators to do it and adding to the confusion about the substance and purpose of the policy. After trying unsuccessfully to get the board to reverse the policy, a group of parents sued, claiming the policy violated the no establishment provisions of the federal and state constitutions.

Foundation of a Constitutional Violation

The constitutional question in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District begins with the first 10 words of the First Amendment to the Constitution: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion." Those words (along with the free exercise clause that follows and the Fourteenth Amendment, making the religion clauses applicable to the states) provide protection for religious liberty and the freedom of conscience. While the Supreme Court's establishment clause cases apply a variety of legal tests and are often criticized for turning on fine distinctions, the principles governing challenges to intelligent design in the public schools are well established.

Nearly 20 years after Epperson, the Supreme Court applied the Lemon test and struck Louisiana's "balanced treatment" statute, a law that forbid the teaching of evolution in public schools unless creation science was also taught (Edwards v. Aguilard [1987]). The Court rejected the statute as an effort "to restructure science curriculum to conform with a particular religious viewpoint." Nearly another 20 years have passed, and federal courts are again seeing cases that challenge the teaching of evolution.

In the years since the Supreme Court last heard a case about religion in science curriculum, the Court has continued to interpret the establishment clause in ways that guard against school-sponsored religious indoctrination. Public school prayer cases, such as Lee v. Weisman (graduation prayer) and Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (prayer at football games), have made clear the ban on school promotion of religion. Other cases, such as Westside Community Schools v. Mergens (upholding Equal Access Act) and Good News Club v. Milford Central School (allowing religious groups equal access to meet on school facilities after hours), have demonstrated the limits on the Establishment Clause and provided protection of religious expression by private actors in the public schools.

The Court's standards have been often applauded by religious liberty advocates who maintain that freedom of religion requires the public schools to be neutral toward religion. On matters of public school curriculum, the general rule is that public schools can teach about religion, but public schools may not teach religion. Most experts agree that this rule applies to the recurring controversy surrounding theories of evolution.

The Dover Decision

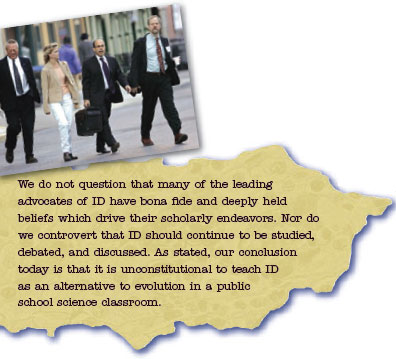

After a six-week bench trial, the federal court found that the Dover policy (promoting intelligent design in public schools) violates the establishment clause. With harsh words toward the board's decision, it permanently enjoined the school board from promoting ID. In a 139-page decision the court recounted extensive testimony from those who advocate ID and the scientific community that rejects it. In sum, the court found the school board had endorsed and advanced a religious idea, and had done so with a religious purpose.

Applying Lemon, the court found that the language, legislative history, and historical context in which the ID policy arose inevitably led to the conclusion that Dover consciously chose to change its biology curriculum to advance religion. The court identified numerous examples of board members attempting to promote their own religious views in the curriculum. The court found that board members had introduced a religious conflict into the classroom by proposing a policy that appeared to make students choose between God and science.

While the court's finding of a clear religious purpose was legally sufficient to strike the policy, it went further, agreeing to answer the question urged by the plaintiffs of whether ID is science. Anticipating objections, the court said it "was confident that no other tribunal in the United States is in a better position than are we to traipse into this controversial area" (p. 63). It cited expert testimony that revealed ID not as a new scientific argument, but rather as an old religious argument. Based upon all the evidence presented, the court held that intelligent design, at least as posited at this time, is not science. The court defended its finding as essential to the primary constitutional question, noting that its decision "may prevent the obvious waste of judicial and other resources which would be occasioned by a subsequent trial involving the precise question which is before us" (p. 64).

Conclusion

While the court found that the ID movement could not be separated from its creationist roots, the court was also careful to make clear that it had no position on the veracity of religious arguments about the existence of God. It stated: "We express no opinion on the ultimate veracity of ID as a supernatural explanation" (p. 89). In making this distinction, the court recognized that its decision rested on the context of religion in the public schools. The court decision was not intended to end discussions and debates about intelligent design. Instead, it simply affirms the law that protects religion and religious liberty by ensuring that religious matters are left to individuals and faith communities, not delegated to public school officials.

Indeed, debates about intelligent design and other challenges to scientific teaching will undoubtedly continue. In the last couple of months, conflicts over the teaching of ID in a philosophy class in California and proposed changes to science standards in Ohio have been in the news. Perhaps it will take another case to reach the Supreme Court before we see this wave of controversies decline. In the meantime, the Dover decision deserves careful attention. Its thorough treatment of ID is persuasive authority against the latest attempts to advance religion in the public schools.

K. Hollyn Hollman, general counsel of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, Washington, D.C.

Article Author: Holly Hollman

Holly Hollman serves as general counsel and associate executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, where she provides legal analysis on church-state issues that arise before Congress, the courts, and administrative agencies. She is a member of the U.S. Supreme Court, D.C. and Tennessee bars.