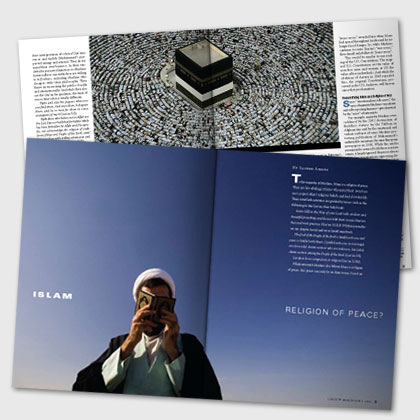

Islam: Religion of Peace?

Saleem Ahmed March/April 2009

To the majority of Muslims, Islam is a religion of peace. They are law-abiding citizens who mind their own business, respect others’ religious beliefs, and lead a low-key life. Their interfaith activities are guided by verses such as the following in the Qur’an, their holy book:

Invite (all) to the Way of your Lord with wisdom and beautiful preaching; and discuss with them in ways that are best and most gracious (Qur’an 16:125) (Within parentheses are chapter (sura) and verse (ayah) numbers);

The food of the People of the Book is lawful unto you and yours is lawful unto them. (Lawful unto you in marriage) are (not only) chaste women who are believers, but (also) chaste women among the People of the Book (Qur’an 5:5);

Let there be no compulsion in religion (Qur’an 2:256). While extremist Muslims also believe Islam is a religion of peace, this peace can only be on their terms, based on their interpretation of selected Qur’anic verses and hadith (Muhammad’s purported sayings and actions). They do not mind their own business. In their vendetta for perceived injustices to Muslims historically or currently, they are willing to kill others, including Muslims who disagree with their philosophy. They thrive on terrorizing the public—locally and internationally. And while they also use the Qur’an for guidance, the tenor of verses they select is totally different:

Fight and slay the pagans wherever you find them. And seize them, beleaguer them, and lie in wait for them in every stratagem (of war) (Qur’an 9:5); Fight those who believe not in Allah nor the Last Day nor hold that forbidden which has been forbidden by Allah and His apostle, nor acknowledge the religion of truth (even if they are) People of the Book, until they pay Jizya with willing submission and feel themselves subdued (Qur’an 9:29); Take not Jews and Christians for your friends and protectors. . . . And he amongst you that turns to them (for friendship) is of them (Qur’an 5:51).

While thoroughly confusing messages when taken as “snapshots” frozen in time, these “mixed signals” in the Qur’an represent an evolution in the divine message Muhammad received over the 23 years of his prophethood (610-632 C.E.). While guidance on spiritual matters remained unchanged, that on temporal matters evolved after he fled from Mecca (622 C.E.) and was welcomed as head of state in Medina. Responding to fluctuating sociopolitical developments, these verses guided Muhammad on how to respond to threat: with equal force, or with diplomacy and compassion.

The Challenge Muslims Face

Unfortunately, the Qur’an is not arranged chronologically. For example, guidance permitting Muslims to eat with and marry “People of the Book” (Jews and Christians) is followed 46 verses later—in the same sura—by guidance prohibiting Muslims from trusting them. While this gives the impression that initially Muslims could trust Jews and Christians but were later advised against this, actually the opposite happened: Muhammad was cautioned against trusting “outsiders” earlier in his ministry when he was a marked man with a price on his head; and the reconciliatory posture toward “People of the Book” was part of the last message he received around 632 C.E., when Islam had spread throughout Arabia and he no longer faced the same danger.

While the prophet lived, no need was felt to consolidate all guidance he had received as this was an ongoing process. The need for consolidation took on urgency after a particular battle, one to two years after Muhammad’s death, in which several Qaris (who had memorized the divine guidance) were killed. Fearing that Muslims would be lost without a central repository of prophetic guidance, Umar (later the second caliph) suggested to Abu Bakr (then caliph) to consolidate all revelations into one book. Initially reluctant to do something that had not been “sanctioned by the prophet,” Abu Bakr asked Zaid, another close companion of Muhammad, to coordinate this project. Zaid collected verses written on “leafless stalks of the date-palm tree and pieces of leather, hides, and stones, and from the ‘chests of men’ (who had memorized verses).” The Qur’an thus compiled contains more than 6,200 verses, arranged in 114 suras of unequal length. The shortest has three verses (sura 108); the longest, 286 (sura 2). While some Muslims believe Muhammad had instructed his followers on the placement of verses, others believe this was a later decision. Probably both happened to varying degrees.

Qur’an’s Divergent Interpretations

Since Qur’anic verses indicate neither context nor chronology of revelations, some Muslims freely pick whichever guidance and/or hadith supports their agenda at any time, ignoring other guidance suggesting the opposite. The consequence of this pick-and-choose approach is exemplified by the following divergent writings on terrorism, all quoting verses from the Qur’an: (1) press releases from the Fiqh (Islamic law) Council of North America and Islamic Society of North America (both dated July 25, 2005) condemning terrorism, labeling suicide bombers as criminals/murderers, and promoting Islam as a “Religion of Peace;” and (2) an article by Saudi Arabia’s former chief justice Sheikh Abdullah bin Muhammad bin Humaid inciting Muslims to constantly fight unbelievers and projecting Islam as a “Religion of War.” Reading this 19-page article (included in the book Interpretation of the Meanings of the Noble Qur’ân in the English Language by Al-Hilali and Khan [Riyadh: Darussalam Publishers, 1996], suicide bombers shine as martyrs.

Thousands of Muslims circle the Kaaba at prayer during the hadj in Mecca. REUTERS/Ali Jarekji

The extremists’ puritanical vendetta against other Muslims may also be gauged from the following five headlines in the newspaper Dawn (Karachi) during April through September 2007, mostly involving Lal Masjid, a pro-Taliban group in Pakistan: “Lal Masjid Threatens Suicide Attacks”; “Anti-polio Campaign Thwarted by Clerics”; “Woman and Three Men Publicly Executed”; “Lal Masjid Fatwa Against Magazine”; and “Women Beheaded for ‘Immoral Activities’” (April 7 and 27, June 5 and 17, and September 8, respectively).

That extremists have little following worldwide may be gauged from the absolute routing of orthodox Muslim parties in Pakistan’s 2008 elections. While they had won 20 percent of the seats in Pakistan’s National Assembly in 2002 and formed governments in the two provinces bordering Afghanistan and Iran, they won less than 5 percent of the seats in 2008 and also did poorly in these two provinces. In fact, the 2002 results probably represented a “protest vote” against the U.S.A.’s massive bombing in adjacent Afghanistan. Similarly, the 2008 results clearly showed people’s protest against extremism.

Undeterred by their increasing unpopularity, however—but having more faith in bullet than ballot—extremists march on, destination unknown.

Hidden within Qur’anic passages we also find an antidote for extremists’ blind use of selected Qur’anic verses. This is in the form of another Qur’anic verse: None of our Revelations do we abrogate or cause to be forgotten, but We substitute something similar or better (Qur’an 2:106).

Thus, earlier Qur’anic guidance on any subject stands abrogated by later guidance. “War verses,” revealed to guide Muhammad in earlier years, when enemies were out to throttle his fledgling religion, should be considered replaced by “peace verses, ” revealed later when Islam had spread throughout Arabia and he no longer faced danger. So, while Muslims continue to recite Qur’an’s “war verses, ” they should only follow its “peace verses” .

This would be similar to our reading of the U.S. Constitution. The original U.S. Constitution set the value of non-free men and women at 3/5 the value of free individuals. And while the abolition of slavery in 1865 repealed this, the original Constitution, preserved in the U.S. Archives, will forever carry that proclamation.

Demystifying Islam as a Religion of War

Since “sensationalism sells news,” the voice of majority Muslims—moderate and self-respecting humans—gets drowned by the “noise” of extremists.

For example, majority Muslims were saddened by the 2001 destruction of Buddha’s statues by the Taliban in Afghanistan and by the emotional and violent outburst of some Muslims protesting publication of Muhammad’s

unfavorable caricatures by some European newspapers in 2005. While the media prominently covered both these reactive events, it largely ignored the press releases of Muslim organizations expressing dismay at both above-mentioned reactive Muslim actions.

Perhaps the media—and publications like Liberty—can help bring to the world’s attention the voice of “Muslim majority protest”? And while at it, the media might also consider investigating the following questions: (1) To what extent do Sheikh Abdullah’s thoughts reflect the official Saudi position? (2) Should Muslims who unquestioningly follow Qur’an’s “war verses” be permitted to live in or visit countries where such violence is prohibited? (3) Why don’t we hear of extremist leaders killing themselves in suicide missions? Why are their followers so “expendable,” while they decline to sacrifice themselves for a cause?

The bottom line: Yes, Islam can be, and in practice usually is, a religion of peace; but we cannot say the same for all its followers.