Known for Action

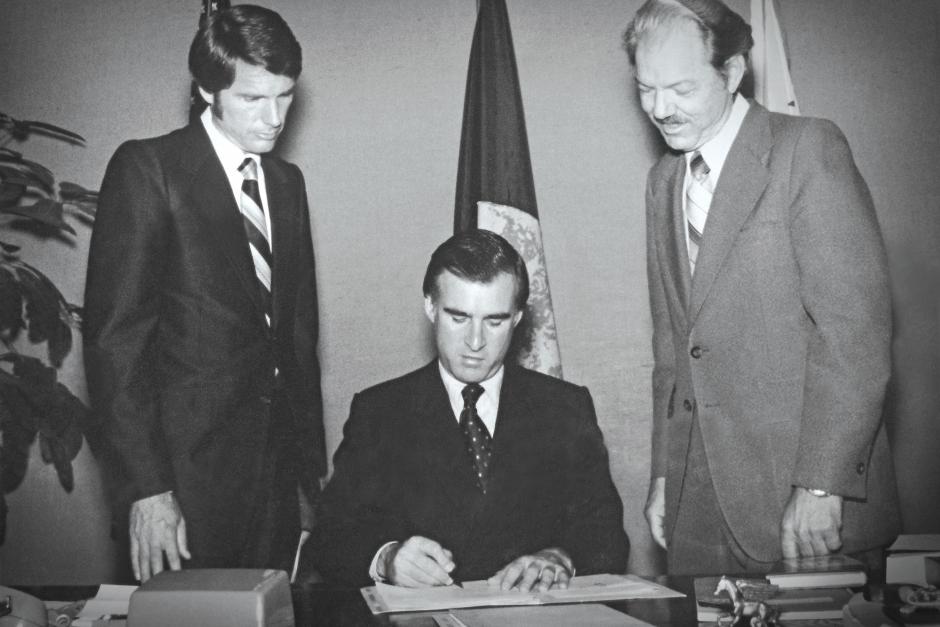

Céleste Perrino-Walker September/October 2014ABOVE: Claude Morgan, Associate Director of Church State Council (left) and John V. Stevens, Sr., Director of Church State Council observe the signing of conscience-exemption legislation by California governor, Jerry Brown.

The Church State Council has worked tirelessly for 50 years to maintain religious freedom, despite relentless efforts by others to minimize that freedom and the wall of separation that protects it.

Founded in 1964, the Church State Council was the brainchild of R. R. Bietz, president of the Pacific Union Conference (PUC) of Seventh-day Adventists, who recruited Warren Johns, a young lawyer, to head it up. Seventh-day Adventists are committed to the preservation of religious freedom, and Bietz wanted an organization that could publicly be identified with religious liberty. Originally formed in response to the proliferation of Sunday laws in the 1960s, following the Supreme Court’s decision upholding such laws, the council battled such laws in diverse places, including California, Utah, and Nevada, with considerable success, believing such laws to violate the separation of church and state.

Since that time the mission of the council has expanded to combat many other assaults on religious freedom. It is important to note that while many organizations are willing to help their own members, the Church State Council has always been willing to help anyone suffering religious discrimination, regardless of their religious affiliation or doctrinal beliefs. The Council has defended freedom for a diversity of faiths from its inception and continues to do so today.

“If religious liberty means anything,” says Alan J. Reinach, esq., who became executive director of the Church State Council in 1994, “it means that we stand up for everybody’s religious freedom. A lot of groups will help members of their own community, but we’re known for helping people of any community.”

Conscience Exemption From Labor Union Support

In 1974 the Church State Council hit a critical juncture because of an active campaign to create collective-bargaining laws for public school employees, local government employees, state employees, and farm workers. Melvin Adams, the director of religious liberty for the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, visited church leaders in California urging them to organize a program to actively influence legislation in Sacramento. In 1974 the Council established an office in Sacramento and recruited attorney Claude Morgan to serve as vice president and legislative affairs director. “For several years conscience exemption from labor union support was almost the total focus of our work,” Morgan remembers.

“At times there was a very chaotic scramble as unions and their supporters maneuvered to propel their legislation along. There were occasions when we would push to get our conscience amendment adopted in a late-night committee meeting—if our amendment was adopted, it was the kiss of death for the bill because the unions had vowed they would not accept our amendment—only to wake up the next morning and discover that the contents of the collective-bargaining legislation that had been defeated the night before had overnight been amended into another bill in another committee and was set for hearing just a few hours later. Legislators supportive of collective-bargaining had introduced bills, and the thrust of support sometimes shifted rapidly from one to another, depending on which bill they saw an opportunity to move forward. I am sure there was no one in the capitol building who did not know that the Adventists were seeking an exemption from the collective-bargaining legislation and that they were not in favor of trade unions.

“Senator Al Rodda, a Democrat from Sacramento, was a teacher and was carrying the school employees’ bargaining legislation. We viewed him as one of our strong opponents, but over time he became convinced of our sincerity and the merit of our cause. He became the author of conscience-exemption legislation for school employees and successfully carried it to passage for us.”

Rewriting Religious Corporation Law

“One of the major issues we dealt with,” remembers Morgan, “was the rewriting of the religious corporation law and the removal of churches from regulation by the attorney general. In 1979 a Los Angeles attorney representing dissident members of the Worldwide Church of God was able to get Attorney General George Deukmejian and the Los Angeles Superior Court to cooperate in placing the church into receivership and taking custody of all church records in a dramatic surprise raid on the church headquarters. During that same time the state legislature was in the process of revising the California corporation law. It was ultimately decided to draft a separate law to cover religious corporations.

“I was an active member of a church advisory committee of about 20 members who worked directly with the draftsman in developing the provisions of that law. Meanwhile, Senator Nicholas C. Petris, a Democrat from Oakland, introduced legislation to remove churches from the oversight of the attorney general. We were very active in the support of that legislation.”

RFRA and RLUIPA

In the late 1990s the Council was involved in the flood of activity at both the national and state level to clean up the mess caused by a series of Supreme Court decisions undermining protection for the free exercise of religion. In the states, a national coalition was working to enact state Religious Freedom Restoration Acts (RFRAs). The Council introduced such RFRA bills in California, Hawaii, and Arizona, ultimately leading a successful effort to pass a RFRA bill in Arizona in 1999.

Efforts to pass a broad religious freedom bill in Congress languished, but led Congress to focus on specific needs, including the rights of the incarcerated and the land use problems faced by religious congregations.

“When the Supreme Court struck down the Religious Freedom Restoration Act with regard to states, they said Congress had the right to remedy specific free exercise problems, but not to invoke a higher standard for free exercise across the board, without evidence of specific problems,” says Reinach. “They needed a record of specific problems that required protection. Two problems—the religious rights of the incarcerated and land use by religious organizations—came up repeatedly. Congress had to establish a factual basis.

“When they went back to the drawing board to enact a fix, they held hearings for a couple of years, and gathered evidence that would support a bill. I provided evidence of cases to Representative Henry Hyde’s office that helped to provide the necessary support for congressional authority to protect religious land use so they could document a genuine problem that needed to be fixed. We made a significant contribution to the record.” The resulting legislation was the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Person’s Act (RLUIPA), enacted in 2000, which is a United States federal law that protects the religious liberty of prisoners and gives churches and other religious institutions the ability to avoid burdensome zoning law restrictions on the use of their property.

Tuition Vouchers

The Church State Council also fought strenuously against approval of tuition vouchers, certificates issued by the government to parents to pay their child’s private school tuition in part or in full. There were ballot initiatives in California twice: in 1993, and again in 2000. “The Council successfully opposed them both times,” says Reinach, who also submitted amicus briefs when the issue of vouchers went before the Supreme Court.

“We tried to explain to the Supreme Court,” Reinach says, “why a pervasively sectarian school was so religious it should not be funded by tax dollars. I surveyed the literature about how faith and values are transmitted in different types of religious schools, and all of them said the same thing: it’s not just the academic instruction, it’s the atmosphere; you’re part of a faith community. You’re part of a group that has shared values. And to say that somehow you can fund the secular aspects without funding the religion . . . that’s impossible. There is no line between what is faith and what is secular in these schools. Such a distinction is purely artificial—it doesn’t reflect reality.”

Vouchers were defeated in California, though the Supreme Court upheld them, ruling that they did not violate the establishment clause prohibition on government funding of religion. “Basically,” says Reinach, “they relied on the legal fiction that the funds go to the parents, rather than to the school. In fact, the parents never see a dime. The money is paid directly to the school.

“Voucher schools are regulated, at least in terms of nondiscrimination rules. Typically, they are not allowed to discriminate. Thus, they lose the freedom to hire faculty and staff who represent their faith. Eventually we can expect voucher schools to be required to conform to state curriculum requirements, losing the freedom to teach, for example, about Creation or marriage from a religious perspective.”

FEHA

The California Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA) is much stronger than federal law in its sanctions against employment discrimination. Surprisingly, religious institutions are completely exempt from its provisions, thanks to the work of the Church State Council. In other words, the California courts cannot sit in judgment on their employment decisions.

“I think this exemption might be my largest contribution to religious liberty,” says Morgan. “The Fair Employment and Housing Commission was sponsoring legislation to expand its authority. The bill was up for a hearing in an assembly committee chaired by Waddie Deddeh, an assemblyman from southern California. I had written to the committee asking that religious organizations be excluded. When I spoke at the hearing, Mr. Deddeh said, ‘We will provide that you can favor members of your church,’ but I insisted, ‘No, that does not solve the whole problem. Please do not put us in a position of entanglement between the church and the state. You don’t want the state to be in a position of passing judgment on church-hiring decisions and deciding which decisions are based on religious considerations and which are not.’

“The author and the committee finally accepted our amendment. Of course, that exemption does place a greater burden on religious organizations to scrutinize their own practices to be sure that employees are being treated fairly, but it has probably avoided church-state conflict in hundreds of employment situations since then.”

Workplace Religious Freedom Act of 2012

When California Assembly member Mariko Yamada introduced the Workplace Religious Freedom Act (WRFA), Council director Alan Reinach was quickly recognized as the subject matter expert on religious accommodation and asked to chair the coalition supporting the bill. It easily passed through a legislature not commonly receptive to religious interests thanks to the skilled leadership of Yamada and her staff, with effective testimony provided by members of the Sikh Coalition, University of California at Davis law professor Alan E. Brownstein, and Alan Reinach.

The bill is a signature accomplishment for the Church State Council, providing Californians with the best protections for religious freedom of any state in the nation. “We were able to pitch it as a civil rights issue rather than a Christian rights bill,” says Reinach. “Basically the bill does three things: it defines undue hardship in terms of significant difficulty or expense. You must accommodate religion in the workplace unless it results in a significant difficulty or expense. Second, it specifies protections for religious dress and appearance that were not in the law previously, giving broad protection for religious dress and appearance to be accommodated in the workplace. Last, it has something no other state does, and that is a nonsegregation measure making it what Mariko Yamada called ‘the Rosa Parks bill of the twenty-first century.’

“There are a number of cases where people who expressed their faith through their appearance have been sent to jobs that do not allow them to engage the public,” says Reinach. “In one case a Muslim woman was taken off the customer service counter and given a back office job. She lost that case because the court said there was no adverse action. She wasn’t fired; she was just transferred.

“There are cases in which stores put someone in the stockroom because they don’t want them out in front of the customers wearing a hijab. The bill prevents the segregation of workers. Combined, these three provisions secure the best protection for religion in the workplace, allowing people of faith to be accommodated.”

The Sikhs came out in force to support the bill, and Seventh-day Adventist Church members wrote letters and e-mails by the score. “Whenever the bill came up for hearing,” says Reinach, “the hearing room was literally filled with turbans.” Reinach also recruited support from the ACLU and the California Employment Lawyers Association (CELA), respected civil rights groups that made the bill much more palatable to a liberal legislature.

Religious Accommodation

Another important aspect of the Church State Council’s work continues to involve Sabbath observance in the form of Saturday work schedules. They receive more than 100 calls for help from Adventist church members every year. “In the early days,” says Morgan, “fax machines were rare, and Federal Express had launched a new service of same-day delivery by their fax system. We often were able to use that service to put a religious accommodation request letter into an employer’s hands within hours of learning about a Sabbath observance problem.

“This was also a time when government agencies were developing equal employment opportunity appeal processes, and I handled administrative appeals for members facing religious liberty problems with government agencies.”

Melvin Jacobson, who has since passed away, worked as an associate director for the Church State Council. Alan Reinach estimates that Jacobson worked in religious liberty for three decades. “He had a real knack for building bridges,” Reinach recalls. “In one of the Sabbath work issue cases he was handling, he drove down to see the owner at his ranch. They spent 45 minutes talking about farming and ranching, then Mel asked him what he wanted to do about the Sabbath work problem. The owner said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about that. That’s handled.’ Mel had a remarkable way with people.”

Freedom’s Ring Radio

For 15 years the Church State Council has broadcast Freedom’s Ring Radio, a nationally and internationally syndicated program produced in cooperation with the North American Religious Liberty Association and hosted by Alan Reinach. The show has produced more than 700 programs and covers news of religious liberty both in America and around the world. The 15-minute show is broadcast globally and heard on six continents.

In the final summation Reinach says: “As Thomas Jefferson once penned: ‘Almighty God hath created the mind free.’ We defend everyone’s right to worship God, or not, because we believe a loving God would have it no other way. Another favorite writer, Ellen White, said: “Love cannot be commanded; it cannot be won by force or authority. Only by love is love awakened.”* For 50 years the Church State Council has advocated for religious freedom in legislatures, courts, and media, and will continue its relentless defense of liberty for all into the future.

* Ellen G. White, The Desire of Ages (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1898), p.21.