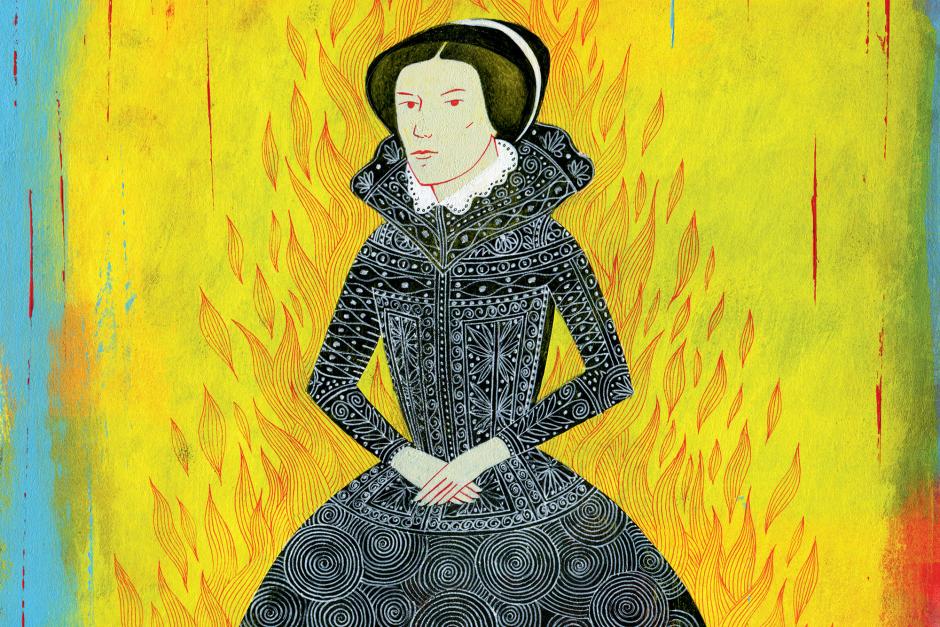

My Body to Be Burned

Albert Spence May/June 2015Today we wouldn’t burn a man alive for what he believes, but our ancestors did. And when you look at the pictures, see what their hands wrote, and look into the faces sleeping in stone and bronze above their bones, they don’t appear much difference from us. Yet they extirpated dissent by burning, and it was a devilish business that we do well to remember.

Four centuries ago the 37-year-old Mary Tudor ascended her father’s throne. For 20 years she had nursed feelings of bitterness at her mother’s wrongs and her own. Her father called her a bastard, and took woman after woman in her mother’s place. Her brother kept her far from his court, neglected and brooding in country manors far away. Her only comfort was the religion her mother gave her, and this she passionately believed to be the truth. Truth was destined to triumph, and the new queen intended to help it along. To begin with, she moved slowly and followed the emperor’s advice to cloak her doings in the apparel of legality; the English have profound respect for law and order. Her first Parliament therefore restored Catholic doctrine as her father had had it, and then went on to heal the breach he made with Rome by renewing the kingdom’s allegiance to the pope. But it soon became clear that trouble was brewing: nearly a quarter of the clergy fled for their lives (including most of the 10 bishops against whom proceedings were opened up); riots broke out in London; and on the last day of the Parliamentary session indignant but unidentified demonstrators seized a dog, gave him a tonsure, shaved his head, as monks do as part of their initiation, put a rope round his neck, and tied a note to his body saying that bishops and priests should be hung. Then they flung him through an open window into the queen’s presence chamber. Mary therefore began to feel that a few executions might have salutary effect and perhaps save much persecution later. So the fires were kindled, even the dead were torn from the grave; either to burn or lie on the dunghill to rot.

Mary’s most distinguished victims were an archbishop and two bishops. Nicholas Ridley, bishop of London, had during the brief reign of Jane Grey preached in the open air outside his cathedral, warning Londoners what to expect if they did not hold to the Protestant Jane. His blunt speaking cost him dearly. When he tendered his oath of allegiance to the new queen, she ordered him straight to the Tower. Hugh Latimer, once a zealous foe of reformation, had accepted the new teaching from a young Cambridge reformer, Thomas Bilney, who had gained his ear by selecting him as his confessor. Henry Vlll had made Latimer bishop of Worcester, and when the king died he had taken a leading part in the great reform that followed. He had been the most popular Protestant preacher of his day. So he knew what fate lay in store for him, but made no attempt to escape. Indeed, Mary wanted him to run like the rest, but he refused to flee. If he scuttled, it would bring ill repute on his cause. So he went to London to seek his fate, and as he passed through Smithfield, where martyrs were wont to die, he remarked with his usual wit that it had long been groaning for him.

For Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury there could be no mercy. He had been a prime mover of reform; he had suggested how to bring balm to Henry’s conscience and a new bride to his bed; he had given the church her English prayer book and communion for the ancient Mass. He had sundered the marriage of Mary’s father and mother and exposed her to the reproach of illegitimacy.

In April 1554 the three bishops left the Tower of London for Windsor and thence for Oxford, there to meet Catholic experts in a great public disputation. If the bishops could be brought to agree that priestly consecration made bread and wine into Christ’s natural body, that nothing of bread remained thereafter, and that the Mass atoned for the sins of quick and dead, they might live. If they couldn’t, they would burn.

Three of Oxford’s most beautiful and historic buildings provided the setting for the mingled splendor and sadism of the ensuing drama: Christ Church, Wolsey’s unfinished college, Oxford’s greatest and grandest—its chapel is a cathedral; the ancient university church of St. Mary, its graceful spire imposing bewitching beauty on the wide sweep of the arterial High and its twisted capillaries of medieval alleys; and the lordly fourteenth century fan-vaulted Divinity School nearby. To hide the ugliness of intolerance, pomp and ceremony invested disputation, trial, and execution with all the trappings of a solemn sacrifice to the Most High.

They began at daybreak on April 14, 1554, with Requiem Mass in Lincoln College—and they were all there: Hugh Weston, college rector and prolocutor, one of the most brilliant controversialists of the day, and experts from Oxford and Cambridge. Immediately after, they heard the choristers of Christ Church sing the Mass of the Holy Ghost in St. Mary’s, and then they signed agreement with the articles under debate. Archbishop Cranmer came in first under guard by “rusty bill men.” He refused to sign articles that were “false and contrary to Holy Scripture.” So too with “sharp, witty, and very earnest answers” did Bishop Ridley. Last the aged Latimer, with kerchief and two or three caps on his head to shield him from an English spring, protested that he had seven times read through the New Testament (the only book they permitted him) without finding a single Mass within. When a beadle, an usher in charge of keeping order, collapsed because of the press, the formalities ended. They ordered the accused to prepare (all bookless as they were) to debate with the commission in one day’s time. The experts were determined to confound them by foul means if not by fair.

At the appointed time they began, this time in the Divinity School. First the archbishop, who held them at bay from 8:00 in the morning till nearly 2:00 in the afternoon. They overbore him in the end with an exasperated cry of “Vicit Veritas.” It was his truth that was winning and not theirs. They disposed of Ridley and Latimer on the succeeding days in like fashion. After this they dropped public proceedings against the bishops for almost a year and a half and worked on them privately, hoping to wear them down into recantation.

Matters at length came to a head when new laws against heresy came into force. Cardinal Pole, the papal legate, then set up an episcopal commission to examine and absolve or degrade and hand the bishops over to the secular authorities. So on the last day of September 1555 Ridley and Latimer were back again in the Divinity School for the preliminary hearing. Next day they stood their trial, which ended almost as a matter of course with their excommunication. On October 15 the bishop of Gloucester and the vice chancellor of Oxford degraded Ridley from his holy orders, and the next day the two men were to go to the stake.

They drove the stake deep and safe into the bottom of the ditch that lay between the city wall and Balliol College; the queen had a strong military force standing by. At the appointed hour the mayor and bailiffs of Oxford produced the prisoners. First Ridley in bishop’s black-furred gown, velvet-furred tippet and cornered cap, walking between mayor and alderman. Further behind, aged Latimer in poor threadbare frock, kerchief on head, and a new funeral shroud around his body. As they passed Bocardo, Cranmer’s jail, they looked up to bid him farewell, but zealous Spanish friars had him busy within, still trying to break him down with disputation. At the stake Ridley ran to Latimer and embraced and kissed him with the words: “Be of good cheer, brother, for God will either assuage the fury of the flame or else strengthen us to abide it.” Little did he know the strength he was to need for what he was to abide that day.

Before the torches were applied they inflicted one more spiritual torment on the martyrs. Dr. Richard Smith, a recanted divine, delivered that last word from a makeshift pulpit before the stake. “‘Though I give my body to be burned’”, he preached, “‘and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing.’” Then he asked them to recant, but the bailiffs rushed on Ridley to shut his mouth before he could reply. They feared the effect of his response. The order to burn rang out, and Ridley removed his clothes, giving the best to the householder whose home had been his prison. What was left he shared among the bystanders, who grasped eagerly for every relic. Meanwhile the executioners stripped Latimer down to his shroud, and soon the smith was chaining them to the stake. As the torches flared among gorse and fagots at his feet the old man’s voice rose above the crackle: “Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England as I trust shall never be put out.”

Death with swift mercy ended the old bishop’s ordeal; he seemed to embrace the flame, bathe his hands in it, and stroke his face with its heat. But Ridley’s sufferings were terrible. They had built the fire badly; heavy solid wood pressed down on the gorse where he stood and prevented the flames from ascending. They smoldered and sulked about his feet and lower legs until they had scorched them to cinder. He writhed like slowly melting plastic in his agony, begging bystanders for Christ’s sake to let the fire rise and do its work. His late keeper, his own brother-in-law, in frenzied distress threw more fagots around him till they hid the struggling martyr from view. Finally, a bill-man had sense enough to drag the fagots clear so as to let the fire burn up. A bag of gunpowder tied about the victims by friends as an act of mercy then took fire, and Ridley fell over his chain at the feet of his companion’s charred remains. It is an ugly thing to see men burning to death. Cranmer saw it all from his tower and indignantly protested to his keeper. Perhaps what he saw unnerved him more than the verbal grilling that still went on and on. Behind him lay defiance of a papal commission sitting in St. Mary’s, before him lay five more months of spiritual struggle. Then the pope’s condemnation came through and on February 14, 1556, the pope’s delegates, the bishops of London and Ely, summoned him to Christ Church.

They read their commission to him in the church and then led him out into Wolsey’s spacious quadrangle for public degradation. One of the bishops was a personal friend, the other an inveterate foe. Both owed him much for their advancement. First they put on him the garments of subdeacon and deacon, then the vestments of a priest, over that the bishop’s robes. But the vesting was done with canvas and old rags. Finally they put on him the primate’s pallium, a canvas maître on his head, and thrust a crude archiepiscopal staff into his hand. The mock vesting complete, they reviled him as brutal soldiery had reviled his Master. “This is the man,” proclaimed his foe, the bishop of London, “that despised the pope, that condemned the sacrament of the altar, that like Lucifer sat in the place of Christ upon an altar.” After this degradation: order by order they stripped off the vestments and at the last set a barber to clip the hair from his head. They even scraped the tips of his fingers to remove the virtue of the holy oil with which he had been anointed. Then they covered his shorn head with a townsman’s cap and put a beadle’s worn-out gown about his unfrocked body crying out: “Now you are lord no more.” Afterward they paraded him through the crowded streets to Bocardo.

But the end was not yet. There came a change of tactics. They translated him from the squalor of Bocardo to the luxury of the deanery at Christ Church. Now he fed on the best of food, he took walks, he played bowls with his persecutors. After this a resumption of the breaking-down process and papers brought for him to sign. He was growing confused now, and he signed them one by one. He accepted the authority and teaching of the church, even on the sacraments. When he had signed four statements, they told him that he was going to burn after all. For the good of his soul he must sign a yet ampler profession of faith. He did, and in so doing repudiated Luther and Zwingli and appealed to all heretics to return to the bosom of the church. In distress he asked for a respite, and Cardinal Pole granted him 11 more days to submit like the penitent thief. On the eve of his execution, the provost of Eton, who was to preach to him before the stake, came down to satisfy himself that he would not at the last moment frustrate them with a retraction.

On the morning of his death the Spanish friar who had disputed with him so tirelessly made him copy and sign yet another recantation to read to the crowds gathering to see him burn. Outside it was too wet and stormy for the stakeside sermon, so they took him into St. Mary’s. They led him in with friars chanting the Nunc dimittis and put him on a hastily erected platform before the pulpit. Once more he heard that he should die like the penitent thief. They called on him to address the tightly packed church.

At first he did what they expected of him. He knelt and prayed with the people; he told them to renounce the world and serve God and his anointed queen. He recited the creed, and confessed belief in the catholic faith of Christ and His apostles. Here, however, he paused: there was, he confessed, one great burden on his conscience: he had signed with his hand what his heart had condemned. “And forasmuch,” said he, “as my hand offended, writing contrary to my heart, my hand shall first be punished therefor.”

For a moment there was shock, then confusion. They shouted at him to remember his recantation; the Spanish friars told him to stick to it; the provost shouted above the commotion: “Stop the heretic’s mouth and take him away.”

They dragged him off the platform; indeed, he ran before them to the stake. As the fire burned up he thrust his right arm into it, holding it in the flames until it burned away, crying only, “This unworthy right arm.”

No; it’s not pleasant to burn men alive like that, and we would never light a fire for religion today. Let a man believe what he will about pope and altar; we have learned to be civilized and tolerant. But it’s just as ugly to behold men rotting in concentration camps and queuing for the gas chamber, to sicken at bodies scorched with napalm or ripped with machine-gun bursts, to shudder at potbellied children with staring eyes dying in front of the world’s television cameras. What precisely is the difference between forcing political belief or practice on the unwilling and persuading to religious conformity with disputation and fire? And when the wheel of fashion turns again, who can be sure that some new frustrated Mary might not make a better job of religious coercion than ever her forbear did with antique fagots and ax?

Article Author: Albert Spence

Albert Spence is a pen name for a longtime Liberty contributor.