New-Look Blue Laws?

Michael D. Peabody September/October 2022For decades religious minorities in America battled state-level Sunday rest laws. Today, are there moves afoot to dust off this old concept of synchronized rest?

If there was any benefit at all to the COVID-19 shutdowns, it was that the world took a much-needed break. Offices, stores, sports, restaurants, and even churches deemed “unnecessary” closed for several weeks. Families spent time at home, getting to know each other, spending more time enjoying nature, and catching up on long-neglected hobbies. Air around the big cities cleared up above the empty freeways. For introverts, it was a gift—no social obligations, just blissful downtime. If it weren’t for the devastation of the pandemic, the synchronized, enforced rest was arguably nice.

For people whose faith mandates a weekly rest day, this period felt like an extended Shabbat or Sabbath. For those unfamiliar with the practice of Sabbath, it was a chance to discover the benefits of unplugging and letting the world go by, teaching us that the world doesn’t need our constant involvement.

One of the keys to Sabbath observance has been the idea that it is communal; that it is a weekly synchronized event that serves to shift our focus. As Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote in his book The Sabbath,1 “Six days a week we wrestle with the world, wringing profit from the Earth; on the Sabbath we especially care for the seed of eternity planted in the soul. The world has our hands, but our soul belongs to Someone Else.”

Yet what happens when one group keeps a different Sabbath from another? Jews and Seventh-day Adventists rest on Saturdays. Muslims recocognize Friday as a special day for prayer. For the vast majority of American Christians, however, Sunday is their day of rest, and it is this reality that has shaped the history of Sunday or “blue” laws in America.

Time-honored Tradition

The reasoning of the late 1800s and early 1900s, when Sunday laws made headlines, went something like this: If a train goes through the town on a Sunday, then there must be people to unload it and care for its passengers. There is increased demand for restaurants, hotels, and taxis. Livestock needs to be moved from place to place and all manner of other support services provided. But if there is no train for one day a week, the level of service can be reduced. Unnecessary labor can be avoided—not just for reasons of religious obligation but because people naturally enjoy a time of rest.

For centuries America has had a patchwork of Sunday rest laws, and today these laws continue to pop up in surprising places. Many states and localities forbid the sale of alcohol on Sundays. You can’t buy a car from a dealership on a Sunday in Nevada, Utah, North Dakota, Michigan, Rhode Island, and Maryland. In Texas, car dealerships must choose whether to shut down on either Saturday or Sunday; sales all weekend long are forbidden. Massachusetts perhaps has the most extended list of restrictions in the United States on Sunday business. Generally, if your business is “nonretail,” it cannot operate on Sundays unless you obtain an exemption. Manufacturers are also shut down on Sundays unless they “require continuous operations” for “technical reasons.”2

Whenever a jurisdiction legislates a day of rest, there must also be exceptions in order to accommodate necessary food service, medical care, and other services. An exhaustive list of dos and don’ts thus becomes essential for the law to be enforced consistently.

set one day apart from

all others as a day of

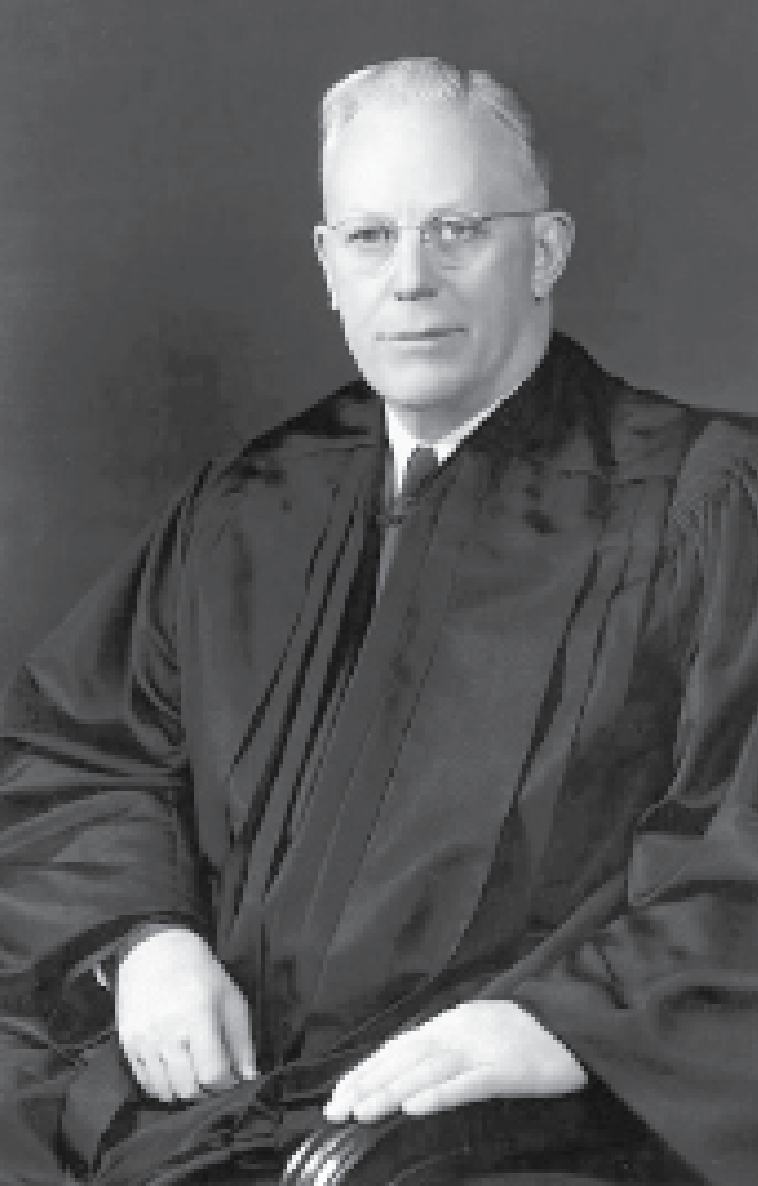

rest, repose, recreation and tranquility . . .”U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren

In 1961 the Supreme Court considered blue laws in McGowan v. Maryland, a case brought by employees of a discount department store in Maryland who were fined for selling specific products, such as floor wax and loose-leaf notebooks, which were prohibited from sale on Sunday. Maryland’s detailed law allowed only certain items, such as medications, tobacco, newspapers, and food, to be sold on Sundays.

The employees claimed this law violated their rights under the free exercise clause. But the McGowan Court found that the employees had only alleged economic injury—their religious practices had not been infringed by the prohibition against selling certain goods on Sundays. The Court said that even though the blue laws historically aimed to promote church attendance, their purpose was now secular: to improve “health, safety, recreation, and general well-being.” That Maryland made the traditional day of worship, Sunday, the day of rest did not mean the state could not use that law to meet secular goals. The Court said that the law did not constitute an establishment of religion.

Justice Earl Warren wrote on behalf of the majority: “The State seeks to set one day apart from all others as a day of rest, repose, recreation and tranquility—a day which all members of the family and community have the opportunity to spend and enjoy together, a day on which there exists relative quiet and disassociation from the everyday intensity of commercial activities, a day on which people may visit friends and relatives who are not available during working days.”3

Since McGowan the Supreme Court has not again addressed the issue of blue laws, and so it remains the law: government-enforced days of Sunday rest are not unconstitutional so long as a religious practice is not compelled or forbidden. The breadth of government authority in compelling businesses to close, and the willingness of most American to comply, was amply demonstrated during the extended COVID-19 shutdowns, which encompassed all days of the week, including weekends.

An Eco-Sabbath?

It is easy to think of blue laws as a nostalgic relic from simpler times, yet support for government-enforced days of rest is never too deeply below the surface. In one contemporary guise, blue laws are being promoted not from a puritanical religious motive—to keep the community from the sin of Sabbathbreaking—but from an environmental angle, as a way to help remedy a crisis of our age.

The Green Sabbath Project is supported by various religious and environmental organizations and encourages people to take a voluntary weekly day of rest. “Is there nothing you can do about the environment?” asks the organization’s website. “Nothing may be one of the best things you can do. One day every week. Do nothing.” The group gives the example of the city of Bogotá, Colombia, which has implemented “car-free Sundays.”

In 2009 Satish Kumar wrote in The Guardian that “using Sunday as a day of rest and renewal would be good for our personal health as well as the health of the planet.” Rather than releasing carbon dioxide emissions by shopping, flying, and driving, Kumar said, “We can and should restore Sunday to a day for Gaia, a day for the Earth.”4

Even Pope Francis was impressed by the changes to the atmosphere during the COVID-19 shutdowns, writing in his September 1, 2020, World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation proclamation: “In His wisdom, God set aside the Sabbath so that the land and its inhabitants could rest and be renewed. These days, however, our way of life is pushing the planet beyond its limits. Our constant demand for growth and an endless cycle of production and consumption are exhausting the natural world. Forests are leached, topsoil erodes, fields fail, deserts advance, seas acidify, and storms intensify. Creation is groaning! . . . Already we can see how the earth can recover if we allow it to rest: the air becomes cleaner, the waters clearer, and animals have returned to many places from which they had previously disappeared.”5

Legacy of Compulsion

There is an undeniable, timeless beauty in the concept of a Sabbath rest. Yet attempts to mandate a day of rest—regardless of the rationale—will invariably carry apocalyptic undertones for those whose religious beliefs lead them to worship on a different day.

The issue of Sabbath legislation was a focus of the first issue of Liberty, published in 1906. At that time Rev. Bascom Robins was quoted as saying, “In the Christian decalogue the first day was made the Sabbath by divine appointment. But there is a class of people who will not keep the Christian Sabbath unless they are forced to do so. But that can easily be done. . . . If we would say we will not sell anything to them, we will not buy anything from them, we will not work for them or hire them to work for us, the thing could be wiped out, and all the world would keep the Christian Sabbath.”

Today renewed enthusiasm for a unified day of rest tends to be less about God’s sake and more for the sake of the planet. Yet calls for mandated synchronized rest, whether for reasons of economics, ecology, or even religion, still carry with them the taint and danger of blue laws and their legacy of compulsion.

1 Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Sabbath: Its Meaning for the Modern Man (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005).

2 See blue law restrictions listed on the Commonwealth of Massachusetts website, https://bit.ly/3uijyED.

3 McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961).

4 Satish Kumar, “Slow Sunday: The Simple Solution to Global Warming,” The Guardian, September 17, 2009.

5 “Message of His Holiness Pope Francis for the World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation,” September 1, 2020, https://bit.ly/3RiA6GK.

Article Author: Michael D. Peabody

Michael D. Peabody is an attorney in Los Angeles, California. He has practiced in the fields of workers compensation and employment law, including workplace discrimination and wrongful termination. He is a frequent contributor to Liberty magazine and editsReligiousLiberty.TV, an independent website dedicated to celebrating liberty of conscience. Mr. Peabody is a favorite guest on Liberty’s weekly radio show, “Lifequest Liberty.”