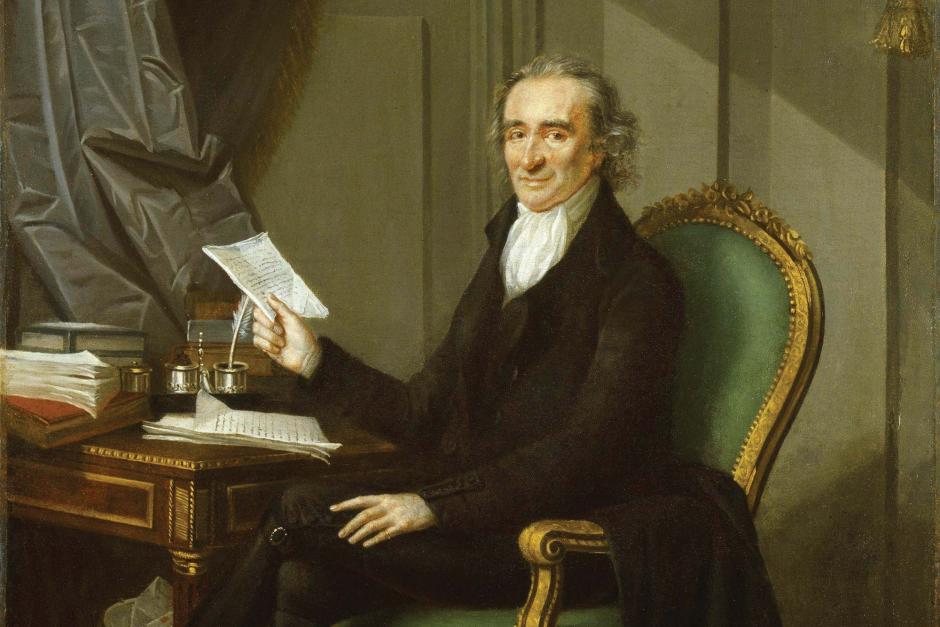

Poor Tom

Ron Capshaw November/December 2020When Thomas Paine died in 1809, Quakers, whom he identified with, refused his wish to be buried in one of their graveyards. Their refusal stemmed from Paine’s attacks on organized religion in general and Christianity in particular. Instead, this best-selling pamphleteer, whom John Adams called “the father of the American Revolution,” without whose “pen” “the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain,” was buried on his farm with only six attendees at his funeral.

In many ways Paine earned this scorn from members of organized religion. Rather than proclaim the Bible the “word of God,” he castigated it as the “word of a demon,” because of its “obscene stories, voluptuous debaucheries, the cruel and torturous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness, with which more than half the Bible is filled.” Of the tenets within the Bible, Paine saw them as harmful, designed to “terrify and enslave mankind.”

Paine attacked the denominations that sprang from biblical interpretation as an assault on reason: “Ido not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.”

And yet this was the same man who declared his “belief in one God,” and credited God with giving man “natural rights” and the ability to discover knowledge through analytical means. He used the Bible to attack the concept of monarchy in general and that of Britain in particular, comparing the latter to that Old Testament period when “kings seduced the Israelites to worship idols instead of God.” He saw positive aspects to the Second Great Awakening because it united Americans across denominational lines and gave them a “sense of patriotism.”

At first glance contradictory, Paine’s religious views in point of fact had a consistent thread. He supported Deism, a religion that credited God with creating a universe governed by natural laws, whereupon God absented Himself from human affairs (Deists compared this noninterfering God to a watchmaker). As such, miracles were not so and prayer useless, and any religious tenet that denied reason and logic and demanded blind faith were monstrous and false. In this regard he was more of a fellow traveler with most of the Founders than many notice. They too were heavily influenced by a Deism that in most cases allowed rather pious generalities about God and Providence while generally following the star of science and human progress.

In that milieu, Paine’s views are not such outliers. “The opinions I have advanced ... are the effect of the most clear and long-standing conviction that the Bible and the Testament are impositions upon the world, that the fall of man, the account of Jesus Christ being the Son of God, and of his dying to appease the wrath of God, and of salvation, by that strange means, are all fabulous inventions, dishonorable to the wisdom and power of the Almighty; that the only true religion is Deism, by which I then meant, and mean now, the belief of one God, and an imitation of his moral character, or the practice of what are called moral virtues–and that it was upon this only (so far as religion is concerned) that I rested all my hopes of happiness hereafter. So say I now–and so help me God.”

In this Paine fit in the mainstream of Deist philosophy. According to historian John Patrick Diggins, Deists believed “that God exists and created the universe. That God gave humans the ability to reason. And that Deists should reject anything that promotes divine revelation (including the Bible).”

Paine had a kinship with British Deists. He shared with David Hume the assertion that there was no such thing as miracles.

But Paine parted company with American Deists on major points. Paine’s closest contemporary, Thomas Jefferson, believed in Jesus as a great moral teacher and that God directly intervenes in human affairs (it is because of this that historian Sydney Ahlstrom has labeled Jefferson a “rational theist”). Jefferson’s belief that God intervened in human events was shared by Paine’s friend Benjamin Franklin, who wrote that “the Deity sometimes interferes by his particular Providence, and sets aside the Events which would otherwise have been produc’d in the Course of Nature, or by the Free Agency of Man.”

Paine’s true religion was democracy, and he hated those who violated it. As such, this gave him a wide variety of enemies, ranging from George Washington to Napoleon to Maximilien Robespierre.

Such a commitment to ideas and not people made Paine frequently a minority of one. While Thomas Jefferson defended the executions of the nobility by the French Revolutionists, and lauded them as fellow democrats, Paine, no lover of nobles, used his position in the newly-formed French National Convention (elected there by French Revolutionists even though he could not speak French) to uphold his opposition to capital punishment, particularly with regard to King Louis XVI (Paine instead wanted him exiled to the United States). This position led to his ouster from the assembly and imprisonment by the bloodthirsty Robespierre.

Eventually freed through the efforts of James Madison, prison time did not result in his compromising his views. A supporter of voting rights for all (as opposed to the Jeffersonian idea that only property owners could vote), he criticized the French 1795 Constitution for not upholding universal manhood suffrage.

Paine also never fit in with those who waged the American Revolution he “fathered.” Federalists hated him for his support of the French Revolution, and his belief that people had the right to overthrow a corrupt government (it was because of the latter belief that John Adams attacked Paine’s political thought as “a crapulous mess”). But Paine was also at odds with Jeffersonian Republicans. Although he shared with them the belief that lawmakers should not have financial ties to businesses, he opposed the Jeffersonian concept that only property owners could vote. He believed that the non-property-owning masses could make informed political decisions. By denying this group suffrage, Jeffersonians, he held, were violating the concept that natural rights were universal and not confined solely to landowners. Unlike Jeffersonian Republicans, he didn’t regard greed as exclusive to the business class. He scorned Washington and Jefferson’s attempts to increase their acreage by claiming lands west of the 13 colonies.

In contrast to the Jeffersonian belief in limited government, Paine, a corset-maker by trade, supported social programs for the poor. He supported government-funded education for all, and a state pension plan to allow those at the age of 50 a comfortable retirement. The revenue for these programs were to come from a progressive tax on the rich.

Much of his social conscience was traceable to Paine’s underprivileged origins. English-born, he was not expensively educated like Jefferson or Madison. He only attended grammar school up to the age of 13, after which he was apprenticed to his corset-making father.

A pamphleteer by his 20s, Paine wrote one urging the British Parliament to better working conditions for the poor. Brought over to America by Benjamin Franklin in 1774. Paine established himself in Philadelphia, considered to be the most radical of the revolutionary cities. There Paine continued his political writings. Appointed editor of a non-political magazine, “American Magazine,” by Robert Aitken, a Philadelphia printer, Paine recast the magazine as a political educator for colonial readers, calling it “a nursery of genius,” designed to make America to “outgrow the state of infancy.”

Paine’s writings in the pamphlet Common Sense(1776) pushed colonial America into an anti-monarchical direction. While the Jeffersonians and Loyalists confined their attacks to an “oppressive” English Parliament, Paine attacked the monarchy as a whole. In contrast to the view among some revolutionaries that the mother country had a usable democratic heritage for colonists to replicate, Paine saw English monarchy as corrupt and anti-democratic. He noted that only one chamber of the British monarchy, the House of Commons, was democratically elected. Paine attacked the “divine right of kings” with the scientific method, which required provable fact. He demanded that King George III “prove” he was appointed by God.

Paine’s attacks on the monarchy horrified American Loyalists who believed America should replicate the English model of government. Loyalist James Chalmers wrote a rebuttal to Common Sense, entitled Plain Truth, in 1776. He stated that the absence of monarchy in the colonies would result in mob rule.

Nevertheless, Common Sensewas a best seller—50,000 copies read by 2 million readers in three months—and made the case for a complete political rebellion against all things British. With this separation Paine believed the United States was akin to John Locke’s “blank slate,” and could start anew as a republic based on “natural rights.” But unlike Jefferson or the Federalists, Paine believed that America could become a utopia. Jefferson believed that democracy had a limited life span; that once land ran out for his republic of landowners, tyranny would ensue. James Madison had no illusions about human beings being made better, and constructed the United States Constitution to deal with humanity’s ever-present power hunger.

Paine faced considerable risk throughout his life for being a minority of one. His attacks on Robespierre almost resulted in his execution at the height of the Reign of Terror. His denouncements of the financial connections of American lawmakers to business interests led to him being physically attacked in the streets. Because of his support for the French Revolution while living in England, the monarchy assigned government agents to monitor him, and there is evidence ofattempts of instigated mob violence against him.

The late author and sceptic Christopher Hitchens once located the hostility toward George Orwell (a pamphleteer who modeled his politics and plain literary style on Paine) from both left and right by pointing out that Orwell by example showed that one could resist the context of the times and be consistently democratic. In this, Hitchens could have been exampling Paine. Unlike Jefferson, whose slave owning made his political writings at times hypocritical, Paine was anti-slavery. Nor did he court business interests to line his pockets, as did the Federalists.

This point of hostility was evident in a quote from an obituary about him in the American Citizen: “He had lived long, did some good, and much harm.”

But Paine was no doctrinaire and was a true intellectual—and by his terms, a rationalist—in that he was always searching for answers; for better ways to establish democratic governing. Toward the end of his life he praised the Iroquois Indians. He saw them as combining a harmony with nature with a democratic mode of governance. It would be hard to imagine Jefferson taking this tack, as he arguably regarded those of “other colors” to be at least intellectually inferior to Whites.

And Paine has left a legacy and usable ideology for Americans. Ronald Reagan, who frequently identified himself as a Jeffersonian democrat, favored Paine’s optimism over Jefferson’s gloom. He used Paine’s expression “We have it in our power to begin the world over again” and applied to a post-cold war world. And FDR cited Paine’s proposed state-funded pension to those wanting to retire at the age of 50 as the basis for the president’s Social Security program.

---------------------

Paine is somewhat of a conundrum. His views on religion are inflammatory to Bible-believing Christians even today. Pioneer Adventist visionary Ellen White was sure Paine was destined for hell—as are undoubtedly multitudes of other public figures who have neglected or denied their own faith calling. But that is a personal tragedy for Paine, quite apart from his formative influence on the new republic and ideas about civic freedom that resonate today. In fact, I think it axiomatic that one cannot understand the ongoing experiment with democracy that is the United States without reading and appreciating poor Thomas Paine.—Lincoln Steed, Editor.

Article Author: Ron Capshaw

Ron Capshaw is a journalist and freelance writer in Midlothian, Virginia.