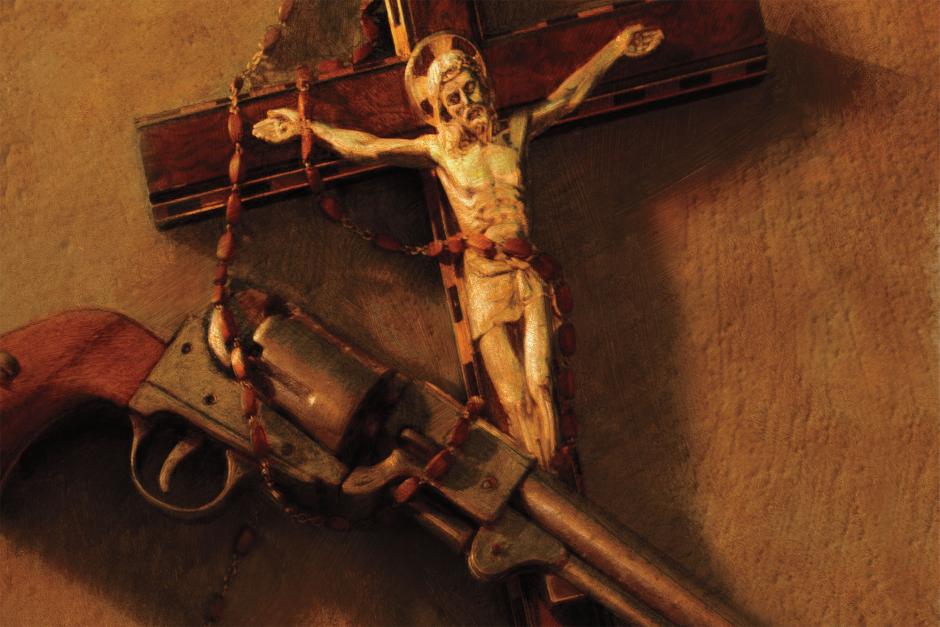

Revolution and Redemption

Martin Surridge March/April 2015During an era when the British Empire had spread its influence to all corners of the globe, lining their pockets with wealth and ancient artifacts, it is perhaps comic retribution that one of Britain’s most enduring imperial-era legacies in Central America is what we remember from a bumbling English novelist and failed spy.

The seriousness of the circumstances likely undercuts the amusing nature of his travels; nevertheless, Graham Greene’s accounts of his visit to Mexico are simultaneously bizarre and informative, both astounding and heartbreaking.

Greene was the writer of two books addressing government persecution of the Catholic Church that he observed in Mexico during the 1930s: a nonfiction travelogue entitled The Lawless Roads, along with a novel, The Power and the Glory, about a morally weak, alcoholic priest seeking refuge from hostile authorities. At the geographic center of both of these is what Greene labels the “Godless state” of Tabasco, ruled by the aggressively anti-Catholic Tomás Garrido Canabal. It was in this land that Greene wrote some of his greatest work. Today many regard Greene, author of several other notable novels, such as The Quiet American and Brighton Rock, as one of the premier English-language novelists of the past hundred years. Indeed, Richard Grabman, author of Gods, Gachupines and Gringos: A People’s History of Mexico, calls Greene “a towering figure of twentieth-century literature,” yet at the same time Grabman questions his Mexican mission, dismissing him as a “clueless Englishman, a newspaper reporter who wrote detective fiction.”1

If such remarks seem inconsistent, it may be because that nearly everything about Greene’s time in Mexico seems a little baffling. Eager to explore the chaotic region in writing through the blurring of both fiction and fact, Greene interlaced his own personal spiritual struggles with those of the Mexican people. He discovered how contradictory the peasant attitude toward religion can be, and received a mixed response from friends in high places who could not decide whether to praise the stories of this reporter-turned-spy-turned-novelist as heroic accounts or condemn them as heretical.

In order to understand the Mexico into which Greene entered, in the aftermath of the state suppression of the Catholic Church known as the Cristero War, or La Cristiada, it is important to appreciate the significance of the nation’s fiercely contested land. In both his novel and his journalistic recordings, Greene focuses heavily on the terrain of Mexico, its hills and soil, rocks and rivers. In his Lawless Roads description of Tabasco, however, Greene hardly wrote of the region as a desirable place. It was to him a quagmire, “a swamp, with a mud river [alongside] a mud bank, like landing at the foot of a medieval castle [with a] ramp of mud and old tall threatening walls.”2

Greene’s descriptions of Tabasco are indeed haunting, almost tragic at times, but his fish-out-of-water, droll Englishness cannot help eliciting a chuckle from time to time. He describes himself on a riverboat, trying to escape the mosquitoes that had a “terrifying steady hum like that of a sewing machine” by going below deck, but found it so hot in the cramped conditions that he resorted to lying naked under a net, sweating profusely and drying himself with a towel. Greene also described his nauseating encounters with Mexican cuisine: “At mealtimes they made a shocking kind of coffee” and a cook provided him with “a loaf of bread and a plate of anonymous fish scraps from which the eyeballs stood mournfully out. I couldn’t face it,” he wrote, “and rashly made my way to the privy.” Privies, better known as bathrooms in the United States, make up several other amusing anecdotes of this slapstick Englishman: “Twice I dashed for the privy,” Greene wrote, “and the second time the whole door came off in my hands and I fell onto the floor.”3

Subtlety and espionage were likely not among Greene’s fortes. He would end up leaving Tabasco with a sour taste in his mouth, from things much more troubling than a plate of fish eyes. In The Lawless Roads he wrote that “Tabasco was a state of river and swamp and extreme heat” where the common people were prohibited from attending any church left standing. Anti-clerical fanaticism prevented them, as Greene would write, from enjoying their village’s “one spot of coolness out of the vertical sun, a place to sit, a place where the senses can rest a little while from ugliness. Now in Villahermosa, in the blinding heat and the mosquito-noisy air, there is no escape at all for anyone.”4

In Greene’s Tabascan novel The Power and the Glory, the motif of escaping is ever-present. For the long-suffering protagonist, the nonconforming “whiskey priest,” life itself has become one constant attempt at escaping the anti-clerical soldiers—including one diabolically determined lieutenant, based upon Garrido—who would have him executed. Despite his noble efforts providing Mass and confession to needy villagers, the priest is a paragon of immorality. His alcoholism is absolute, and he has fathered a child with a woman in his parish. He is lustful, selfish, and cowardly, and, notably, it is only through his persecution and eventual execution that he finds atonement. For readers at the time, the impoverished, persecuted priest who sleeps in animal dwellings represented a profound reversal of seemingly irreversible, sacred traditions.

For many centuries the Catholic Church in Mexico enjoyed a position of comfort and privilege, but its position as a significant landholder was of particular irritation to the common people, who would launch a monumental national revolution in 1910. The issue of land reform constituted the most frequent and longest-lasting complaint against the Catholic Church in Mexico. Once the Spanish withdrew, taking with them significant economic scaffolding, in order “to pay for imports and foreign services, Latin American nations turned to the production of agricultural commodities for which there was great European demand. This shift meant that the rural areas became more important than old colonial urban centers. The production of foodstuffs for the exports market raised the value of land and led governments to confiscate the lands of the church.”5 Successful land confiscation efforts led to an unsurprisingly frustrated priesthood, who would go on to support an ultimately unsuccessful foreign coup. Along with their conservative counterparts in government, “Mexican clerics invited the Austrian Habsburg archduke Maximilian to become the emperor of Mexico [while] Napoleon III of France, who portrayed himself as a defender of the Roman Catholic Church, provided support for this imperial venture,” which would be doomed to fail only three years after it began.

Opposition to the French invasion began with the Mexican victory at Puebla on May 5, 1862, an event commemorated today as Cinco de Mayo, and would culminate a few years later when “resistance forces captured the emperor and executed him [and although] the Mexicans had been victorious, their vulnerability to foreign powers had again been exposed.”6 The people did not forget the involvement of the clergy, and tensions between the church and populist movements, specifically over the issues of land and influence, would simmer for decades.

Following the Mexican Revolution, which lasted from 1910 until about 1920, and the intense suppression of the church that came as a direct result of clerical resistance to the 1917 constitution, much of the Catholic population rebelled. Enrique Krauze, author of Mexico: Biography of Power, described the backlash against the laws of President Plutarco Elias Calles—specifically Articles 3, 19, and 130 of the Mexican constitution: “There were riots, demonstrations, fighting in the streets [because] church schools were closed and foreign priests expelled. They included punishments for crimes related to religious teaching and worship. Article 19, the most inflammatory, made the official registration of priests obligatory before they could exercise their ministry.”7

The response to anti-clerical fervor reached its apogee during La Cristiada. The swift counterrevolution of the peasants—who, historically, had often been at odds with the wealthy church—likely surprised Mexico’s president. Calles, in what Krauze calls a “battle against religion and crusade for secular enlightenment,” believed he would be able to “suppress the people’s ‘fanaticism’ by cutting it off at the roots.” However, “a huge sector of the peasant population of ‘Old Mexico’ contradicted his illusions in armed rebellion. For them, the ‘cause’ was clear: They were fighting to bring back masses, they were fighting to defend religion. Their war cry was Viva Cristo Rey!” meaning, “Long Live Christ the King!”8

The aftermath of what followed next became what Graham Greene wrote of in The Lawless Roads, calling it the “fiercest persecution of religion anywhere since the reign of Elizabeth. The churches were closed, Mass had to be said secretly in private houses, to administer the Sacraments was a serious offence. But Mexico remained Catholic; it was only the governing class—politicians and pistoleros—which was anti-Catholic.”9

Lasting from 1926 to 1929, the Cristero War would eventually spread to 13 states throughout central Mexico, and came close to resembling the recent wars of religion waged in the rugged mountains of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Krauze describes the conflict: “It would be a savage war on both sides, pitting groups of mounted guerrilla fighters against a federal army that had recently been modernized. The modernization had followed the European model, concentrating on infantry supported by artillery and aircraft, and it had left the federal weak in cavalry essential for fighting in the territory of the Cristiada, where there were few highways and entire regions inaccessible to ground troops. Calles thought the uprising might be over in a couple of months. But without any real central organization, the peasants fighting for their religion became bands of guerrilla warriors, capturing weapons from their enemies and waging a ferocious war.”10

Krauze lists the damages: by the end of the bloody rebellion, the federals had hanged men, burned villages, and “shot priests, about ninety of whom were executed during the war. Twenty-five thousand Cristeros had died in combat. The Cristiada cost upward of 70,000 lives, [caused] a precipitous drop in agricultural production, a decline of 38 percent between 1926 and 1930, an internal migration of 200,000, as well as an external migration, mostly to the United States, of 450,000 people.”11

Greene, himself a devout Catholic convert, made his journey to Mexico in 1938 to observe this devastation and witness the Cristiada’s aftermath firsthand. Among those who had survived the war, he discovered despair and resignation. From one interview Greene conducted, a woman explained that when they died they would “die like dogs [and] no religious service was allowed at the grave.” In another discussion with a villager from Villahermosa, Greene learned just how complex and sometimes paradoxical the relationship between the church and its members could be. When speaking with the local dentist, Greene argued against the dentist’s assertion that going against the church “never pays.”

“But he seems to have won,” Greene said. “No priests, no churches . . .”

“Oh,” the dentist said illogically, “they don’t care about religion round here. It’s too hot.”12

These experiences would become part of his later novel, The Power and the Glory, but Greene’s voyage was about much more than artistic and literary ambition. Grabman explains, “Hired by a Catholic newspaper, Greene went to Tabasco to write an undercover report on religious persecution. He was an incompetent spy and an unhappy tourist—but a brilliant writer.”13

The anti-clerical barbarism that Greene observed in Tabasco, which he would use as the setting for The Power and the Glory, originated nearly entirely from the office of the state governor, the quasi-Fascist dictator, rabidly anti-Catholic Tomás Garrido Canabal, Tabasco’s persecutor-in-chief. Despite the cessation of Cristero hostilities in most parts of the country, “in the crucial oil state of Tabasco, Tomás Garrido Canabal was left as governor. He used his position to launch a crusade against the old enemies of the people—the rich and the church. He rewrote state laws to limit the Catholic priesthood to married men over 60—since Catholic priests could not be married, this effectively outlawed priests—and decreed the death penalty for nonconforming priests.”14

Among Garrido’s most distasteful acts include naming “his prizewinning seed bull after the pope, making fun of clerical celibacy.” Much more horrifyingly, “for the edification and entertainment of the people, he had the cathedral in Villahermosa blown up. Garrido took a more sinister turn with the ‘Red Shirts,’ modeled on such political gangs as Mussolini’s ‘blackshirts’ and Hitler’s ‘brownshirts.’ They were sent to beat up Garrido’s opponents, smash up churches, and organize antireligious ceremonies, usually featuring desecration of religious objects.”15

Greene himself learned how Garrido, who was also an anti-alcohol crusader, installed within his Red Shirts such an anti-religious fervor that they even crossed into neighboring Chiapas hunting for priests or churches. He referred to Tabasco as the “isolated swampy puritanical state of Garrido Canabal—who, so it was said—had destroyed every church. A journalist on his way to photograph Tabasco was shot dead in Mexico City airport before he took his seat. Private houses were searched for religious emblems, and prison was the penalty for possessing them. A young man I met in Mexico City was imprisoned for wearing a cross under his shirt.”16

The observations Greene makes within The Lawless Roads become most interesting in how they provide so directly the source material for his novel The Power and the Glory. The origin of his fictional story about the whiskey priest who lives in hiding is not difficult to identify. Greene heard, while approaching Tabasco by boat, that in that state “every priest was hunted down or shot, except one who existed for ten years in the forests and swamps, venturing out only at night; his few letters . . . recorded an awful sense of impotence—to live in constant danger and yet be able to do so little . . . hardly seem worth the horror.” Speaking later in Tabasco with a local doctor, Greene “asked about the priest in Chiapas who had fled. ‘Oh,’ [the doctor] said, ‘he was just what we call a whiskey priest.’”17

In The Lawless Roads Greene recorded the sights and sounds, and spoke with the dockworkers, dentists, and doctors of Villahermosa, the town that would serve as inspiration for the fictional locale in The Power and the Glory. In one instance he takes a solemn walk to visit the remains of the dead. Greene, the journalist, writes:

“The only place where you can find some symbol of your faith,” he reflected, “is in the cemetery up on a hill above the town. [There is] a great white classical portico, the blind wall round the corner where Garrido shot his prisoners, and inside the enormous tombs of aboveground burial, crosses and weeping angels. [I get] the sense of a far better city than that of the living at the bottom of the hill [where] I visited with the dentist.”

The reader encounters many of Greene’s very same observations in The Power and the Glory, although through his lens of imagination instead. In the opening pages of his novel, the narrator expresses an equally dim, though categorically fictive, view of the region, its geography, and its leadership. Greene, the novelist, writes: “The Treasury, . . . a dentist’s, the prison . . . and the steep street down past the back wall of a ruined church. . . . The whole town was changed; the cement playground up the hill near the cemetery where iron swings stood like gallows in the moony darkness was the site of the cathedral. . . . The lieutenant lay on his back with his eyes open. He remembered the priest the Red Shirts had shot against the wall of the cemetery up the hill, another little fat man with popping eyes.”18

With so many of the Englishman’s passages from his nonfiction travelogue serving as inspiration for fiction, it leaves an impression on those who read both books that maybe Greene grew conflicted over the best way to impress upon others the gravity of the situation in Tabasco. It could suggest that perhaps Greene was unable to let go of his experiences in Mexico, was unable to detach himself from the fight for Catholic belief that he witnessed, and that perhaps the author’s problems ran deeper than textual criticism. Richard Grabman explains that in so many of Greene’s novels the writer couldn’t help returning “again and again to the problem of holding on to one’s beliefs, often Roman Catholic beliefs, under stress.”19

Greene’s theology of redemption through persecution and the desire for the spiritual alleviation of guilt clearly applied as much to his own life as that of his characters. However, even the theology of The Power and the Glory, like the whiskey priest himself, could not escape the clutches of watchful authorities. Like his blurring of fiction and fact in Tabasco, his theology also muddied the waters to the point of ambiguity, according to Peter Godman of The Atlantic:

“Although [the whiskey priest] anticipates his execution,” Godman explains, “and knows that he is walking into a trap, he chooses to perform what he sees as his duty and attempts to give the last sacraments to a fatally wounded criminal. The priest puts the chance of saving another man’s soul ahead of his own survival. Is this martyrdom? Or is it retribution for moral lapses? The moral and theological criteria of The Power and the Glory are ambiguous—so ambiguous that self-appointed censors sniffed an odor of heresy in the book.”20

It must have been particularly painful for Greene that The Power and the Glory—the novel in which he painfully exposed his own moral shortcomings, risked his safety in Mexico to research persecution, and staked his reputation as a novelist and Catholic reporter to write—created controversy in the Vatican’s halls of power. Despite Greene recording for the world and for posterity some of the worst human rights abuses and religious persecutions taking place against Catholics at that time, the cardinals in Rome were displeased and condemned his book.

So when he met with Pope Paul VI in 1965, it is easy to imagine that all of Greene’s sins and immoralities, his failures as a Catholic, and the years he may have considered as wasted in Mexico were at the front of his mind and that an in-person, papal rebuke of his book was soon to follow.

“Mr. Greene,” Pope Paul VI began, “some parts of your book are certain to offend some Catholics.” The pope understood the concept of Christian redemption, as implied by his following advice to Greene: “But you should pay no attention to that.”

1 Richard Grabman, Gods, Gachupines and Gringos: A People’s History of Mexico (Albuquerque, N. Mex.: Editorial Mazatlan, 2008).

2 Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: William Heinemann, 1955).

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Albert M. Craig, The Heritage of World Civilizations, (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1997).

6 Ibid.

7 Enrique Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power: A History of Modern Mexico, 1810-1996 (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997).

8 Ibid.

9 Greene

10 Enrique Krauze.

11 Ibid.

Article Author: Martin Surridge

Martin Surridge has a background in teaching English. He is an associate editor of ReligiousLiberty.TV, an independent news Web site. He writes from Calhoun, Georgia.