Steal Away

Ed Guthero March/April 2018African slaves trapped in the hell of American slavery embraced Christian faith amid the paradoxes, as their captors spoke of a new nation with equality and liberty for all men. Unfortunately, the liberty wasn’t for them. The repercussions echo down to us today . . .

Mississippi, 1830s

he stifling humidity hangs heavy in the late-night Southern air. Slipping in and out of shadows, a small group of plantation slaves move silently through the woods. Much is at stake: it is far past curfew, assembly is strictly prohibited, and retribution would be brutally enforced. They must not be discovered. Yet something more powerful than the overseer’s lash draws them deep into the woods this night.

Soon, huddled behind quilts and rags roughly hung to resemble a small tabernacle, or “hush arbor,” they will conduct a clandestine church service. The makeshift materials have been painstakingly dampened to muffle the sound of voices from carrying on the night air. Caution is paramount.

The encouraging words of a slave preacher, the heartfelt prayers, the soft sounds of song— simultaneously praise and plea, transport them away from bondage and fill their hearts with hope. They defy the risks for such moments and the dream of freedom.

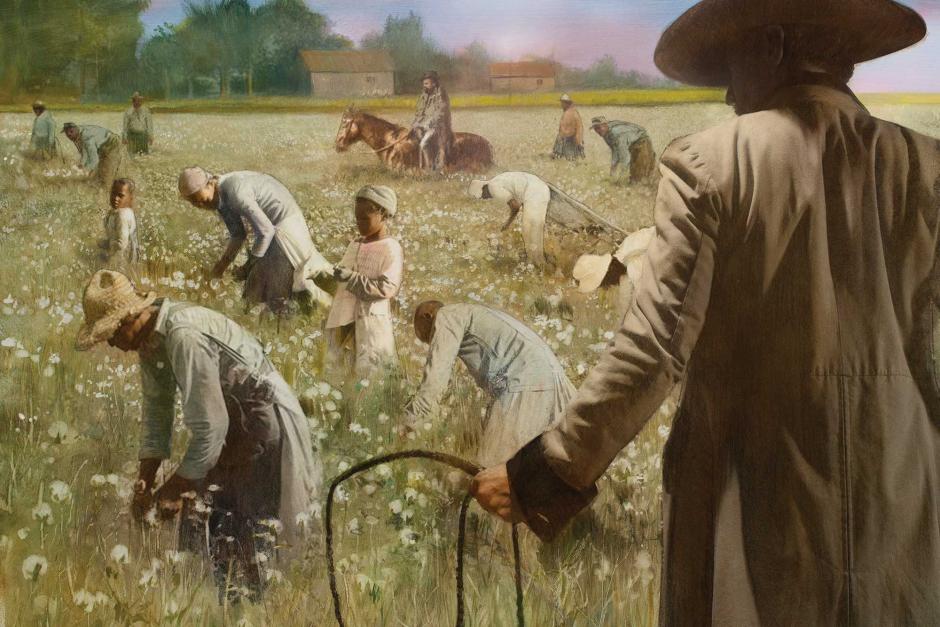

Earlier that afternoon, men, women, and children had toiled in the blazing sun while methodically moving through the planted rows during the back-breaking labor of picking cotton.

A lone voice, conveying both praise and code, would often rise above the sounds of shuffling feet in the fields and the steely gaze of the overseers.

“Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus! . . . I ain’t got long to stay here.” Other voices joined, defying the drudgery, often in the call and response mode that infused these songs of spirit with a communal transcendent fullness.

There would be a secret service that night.

Slave Eli Johnson stated that when he was threatened with multiple lashes for holding prayer meetings, he stood up to his master and declared, “I’ll suffer the flesh to be dragged off my bones . . . for the sake of my blessed Redeemer.”

Not all plantation owners were as unforgiving—some allowed open services. Yet, while a slave service may have been allowed on a certain plantation, on a neighboring one conducting such a gathering would get a participant cruelly whipped or worse. Still, they gathered. In the midst of oppression, captive slaves, despite seeing the blatant hypocrisy of their masters’ actions, had come to seek solace and hope in the Christian religion.

Short decades before, as America’s Founders forged a new nation built on principles of equality and freedom, the practice of slavery coexisted with the words of liberty that echoed through the halls of the Continental Congress. It was an unholy irony then and continued to be as the institution persisted.

In the paradoxical world of Colonial America slavery was at the heart of a massive economy based on human bondage for profit. As profits mounted, blind spots were everywhere.

By 1776 African Americans, victims of the brutal Atlantic slave trade, comprised approximately 20 percent of the entire population of the 13 Colonies. As historian James Norton has said: “Slavery wasn’t a side show in American history; it was the main event.”

Following the end of the French and Indian War, Britain had decided to maintain the expense of keeping 10,000 troops in the Colonies. A series of heavy taxes were pressed upon the Colonies leading up to the American Revolution: The Stamp Act of 1765 and the Tea Tax of 1773 stirred strong feelings of unfair taxation without representation. The infamous Boston Massacre of 1770, during which five colonists were killed by British soldiers in an angry mob confrontation, fueled the flames of revolt. Talk of freedom, liberty, and independence from Britain electrified the Colonies and spread like wildfire.

Slaves heard the stirring talk of liberty and dared to hope it included them, but they were caught in the middle, still considered as property. Yet the irony of a fledgling nation seeking its own liberty while keeping others in bondage was not lost on them. Many colonists as well were uncomfortable with the dichotomy, and the nation’s Founders, a majority of whom owned slaves, wrestled with the incongruence.

In 1774, two years before Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence, an educated former slave from Boston, Prince Hall, petitioned the Massachusetts military governor, seeking the abolition of slavery. Again in 1777, Hall and seven others elegantly presented their case—a virtual Black Declaration of Independence, stating that “they have in common with all other men: a natural and inalienable right to that freedom which the Great Parent of the Universe has bestowed equally on all mankind,” and that “every principle from which America has acted in the course of their unhappy difficulties with Great Britain pleads stronger than a thousand arguments in favour of [the anti-slavery] petitioners, and they therefore humbly beseech that Your Honours give this petition its due weight and consideration and cause an act of the legislature to be passed, whereby they may be restored to the enjoyments of that which is the natural right of all men; and their children, who were born in this land of liberty, not be held as slaves.” The petitions were denied.

Jefferson himself, in the initial draft of the Declaration of Independence, had included wording that attacked Britain’s king and the slave trade: “He has waged cruel war against human nature itself,

violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where men should be bought and sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce.” The passage caused intense debate

and was deleted. In retrospect Jefferson blamed the deletion on delegates who represented merchants with direct interests in

the Atlantic slave trade.

Early in his political career Jefferson spoke out against slavery; he even introduced a Virginia law prohibiting the importation of African slaves. After a time his public voice on the matter faded.

Jefferson wrote that “the institution of slavery was like holding a wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go.”

Brilliant and visionary, Jefferson remains as the great paradox of the Founders, constantly convicted on the issue of slavery. Even as he wrote the words “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” Jefferson possessed slaves. He went on to own 600 slaves during his lifetime, at any one time approximately 100 slaves lived at his Monticello estate . . . skilled craftsmen, artisans, domestic personal, and field workers.

George Washington was also a slave owner. Reflecting on the incongruence of slavery with the ideals of liberty for which he had risked his life, over time his convictions changed. By 1799 he had specified in his will that the 123 slaves that he personally owned at Mount Vernon would be freed at his wife’s death. He also stipulated that older slaves unable to work would be supported by the funds of his estate.

John Adams clearly spoke out against slavery, and Benjamin Franklin was later to become one of the country’s leading abolitionists. Nonetheless, it is a sobering fact to realize that 41 of the 56 signers

of the Declaration of Independence were slave owners. This ongoing contradiction in the founding of the new nation would continue to grind away at the very soul of liberty.

As the emerging American nation began its epic journey of liberty, the brutal Atlantic slave trade still wreaked havoc on the coasts of Africa, and the oppressive slave ships continued their grisly voyages of captive human cargo. Behind the scenes the details of this inhuman subjugation of fellow humans are even more numbing.

From the mid-1400s to the late 1800s, most European powers, notably Britain and Portugal, engaged in the trading of African slaves. It has been estimated that up to 15 million Africans were forcibly kidnapped, violently put in chains, and shipped to the Western Hemisphere during that span. Countless more died during the slave raiding and wars in Africa or in unbelievable conditions of confinement aboard the horrific

“Middle Passage” voyages from Africa to the Americas. In profane alliances rogue African kings, the warlike Ashanti, and corrupt merchants/tribesmen raided other African societies and villages. They then sold captives and war prisoners to the European slave traders positioned along the coasts.

It is staggering to comprehend the inhumanity of the Atlantic slave trade, but when human beings are reduced to property and morals bow to the lure of money, it is beyond nightmarish what can result.

The most notorious episode of the Atlantic slave trade involved the infamous slave ship Zong. During a 1781 voyage to Jamaica, with more than 400 slaves aboard as cargo, water ran out as disease spread among the slaves. The ship’s captain, Luke Collingwood, knowing that insurance would not cover the sick or fatalities caused by disease among his human cargo, but would cover drownings, decided to throw overboard those he deemed too ill to recover. To cut the slave owner’s losses and to claim the insurance, Collingwood callously ordered the drowning murders of 133 slaves.

The disturbing diagram of the Brookes slave ship, first published in Britain during 1788 and widely distributed by anti-slavery groups, remains immoral and appalling in its graphic detail of 450 captive human beings chained and jammed into the cargo holds, virtually unable to move.

As the world’s most dominant power and master of the seas, Britain surged to the forefront of the Atlantic slave trade. British growers established large sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean islands, such as Barbados and Jamaica, where plantation owners grew wealthy on the backs of African slave labor. Simply put, the history of Atlantic commerce is inseparable from slavery, whether in the Caribbean, Brazil, or the Americas.

With perverse justifications, economic profit, and distortions of religion, slavery blended into everyday life. Few citizens stopped to think that the basis of entire economies, their agricultural products, luxuries, and clothing, relied on slave labor. Meanwhile, generations of African men, women, and children were subjugated to lives of forced labor and cruelty. Of the estimated 12 million African slaves transported across

the Atlantic, during the 1600s-1800s era, 2 million perished before reaching the shores of the Atlantic coast.

If evil and injustice are ever to be defeated, someone must speak up. During May of 1787 a dozen devout men met at a London printshop to form the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, among them several Quakers and Anglicans. Longtime abolitionist Granville Sharp and young Thomas Clarkson, whose tireless accumulation of evidence would prove vital to the cause, were present. Abolishing the slave trade consumed Clarkson’s life. He traveled more than 35,000 miles around England in search of witnesses, observing the cruelty of the trade, interviewing, writing notes, and investigating the country’s slave ports, such as Liverpool, where he narrowly escaped death at the hands of a gang of sailors who had been hired to kill him.

William Wilberforce, a brilliant young politician, would use his formidable oratory skills to become the public voice of the abolitionist movement to end slavery in Britain. Wilberforce had experienced a life-changing conversion to Christianity and had considered leaving Parliament and entering the ministry. His friend and mentor John Newton convinced him that he could do more good by serving God in public life and remaining in Parliament.

It would be a long, intense struggle—powerful men who profited by slavery had strong representation in Parliament, but Wilberforce and the abolitionists embraced their mission with a righteous passion.

Clarkson’s gritty research continued to expose the physical horrors of the slave trade and a number of influential pamphlets, written by Methodist founder John Wesley, John Newton, former slave Olaudah Equiano, and others who supported the abolitionist cause were widely distributed throughout England.

The writings of Equiano, who had suffered as a slave, and former seaman John Newton, who had been involved in the slave trade as a ship’s captain in his younger years, had particular weight. Newton had left his hardened, troubled past behind and deeply regretted his participation in the slave trade. Eventually he became an Anglican priest, and his sermons were so popular that the church could not hold all who came to hear him speak.

Open about his past and convicted to fight the slave trade, Newton wrote the high-impact pamphlet Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade, which described the cruelty of the trade and his involvement in it.

Its distribution was highly significant, as was the senior Newton’s ongoing mentorship of the younger Wilberforce in the battle against slavery. His story shows the power of true Christianity to change a life. This is reflected in the emotion of the classic hymn that Newton penned. “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound,” he wrote, “that saved a wretch like me. I once was lost, but now am found, was blind but now I see.”

In 1789 William Wilberforce introduced his first attempt in Parliament to end the slave trade; it was defeated, 163 votes to 88. Opposition to Wilberforce’s bill was fierce; it was to take 17 more stressful years to succeed, as corrupt businessmen continued making a fortune on the slave trade.

Meanwhile abolitionists created a public awareness of the horrific slave trade; and the public mood began to change as citizens were confronted with the dehumanizing reality of treating fellow humans

as property.

Thomas Clarkson and his allies understood the power of evidence, persistence, words and imagery. The Quaker-led Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade during its founding had commissioned a seal/medallion to be designed to symbolize their movement. The image of a kneeling African in chains, captive yet noble, surrounded by the arched wording “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” became the thought-provoking visual symbol of the abolitionist movement. Josiah Wedgewood produced a number of cameos in his pottery factory, and many were shipped to Benjamin Franklin for use in America. Worn not only as engraved cameos, the image was printed and distributed on posters, petitions, and leaflets throughout Britain. Its widespread presence demonstrated the galvanizing role of a powerful image in the struggle for truth and change in society.

Finally, in 1807, after nearly 20 years of struggle, Wilberforce’s bill to end the Atlantic slave trade passed in the British Parliament. That same year his mentor John Newton, now old and nearly blind, peacefully passed away. “Although my memory’s fading, I remember two things very clearly: I am a great sinner, and Christ is a great Savior,” Newton had said.

It is important to remember that the success of the abolitionist movement in Britain was, at its core, the dedication of compassionate Christian people who could not ignore the oppression of their fellow man. Writer David Brion Davis has stated “This was a moral achievement that may have no parallel.”

While many today manipulate and throw Christianity around like a political football, in essence the words of Christ, “to love our neighbors as ourselves and to treat others as we would like to be treated,” so often referred to in the abolitionist movement, are definitive in their simplicity.

Though the Atlantic slave trade was now officially abolished in Britain, and British ships could no longer transport slaves to the New World, paradoxically the institution of slavery itself was still legal.

Abolitionists would continue the fight until Parliament officially ended the damnable practice when the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833was passed. Days after hearing the welcome news,

an ailing Wilberforce died.

That same year, across the ocean in America, thousands of slaves still toiled in the agricultural fields of the Southern states. Though the United States had also banned the Atlantic slave trade in 1808, key events in manufacturing, agriculture, politics, and territorial expansion had fueled the demand for slave labor. The epic 1803 Louisiana Purchase, where the United States automatically doubled its size by purchasing 828,000 square miles from France (land that reached from the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains), opened up a huge amount of additional rich agricultural land in the South. Rice, sugar, tobacco, indigo, and cotton were staple Southern crops, but Eli Whitney’s explosive invention of the cotton gin suddenly made cotton undisputed king in the southland—catapulting the demand for cotton to mammoth levels.

Slave labor to work the cotton fields was in high demand, and the moral momentum gained by abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic was dealt a heavy blow. With the Atlantic slave trade from Africa outlawed in America and England, yet the institution of slavery itself still legal in America, the sinister business of slave trading turned into an internal New World model. Slave families could be separated and sold at market on the whim of the plantation owners, children divided from their parents, husbands from their wives.

Cotton fed the Northern textile revolution within the United States and fueled the nation’s status in international trade as America became the world’s key producer of cotton. Underpinning the ability to make these economic leaps was a slave economy that was held as “the indispensable economic instrument of Southern society.” The North had fostered a form of domestic slavery, while in the rural, agrarian South a more severe system of bondage became a way of life, keeping slave auctions active and lucrative.

Despite economic growth and expansion, potential disasters remained simmering under the optimism of the country. The nation had become a precarious balance of “free” and “slave” states, with a conflicted national conscience out of sync with the ideals of the Declaration of Independence. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” In a few short decades the failure to align practices

and principles were to drive the country to disaster. In 1829 controversial free Black abolitionist David Walker had challenged Americans: “See your Declaration. . . . Do you understand your own language?”

Despite the efforts of abolitionists, in 1790 there were eight slave states; by 1860 the number had increased to 15, while approximately one in every three Southerners was a slave.

Throughout the oppressive surge in American slavery, plantation slaves could see another bitter paradox. Plantation masters had long abused and distorted Christianity to subjugate Blacks while thinking of themselves as superior. Many felt their “property” was of lesser value; some absurdly felt slaves possibly didn’t have souls. They made it illegal for slaves to read, wanting to keep them under control.

Yet, underneath the false air of dominance, slave owners were afraid. Afraid not only of the physical numbers of slaves on the plantations but also of education, the power of knowledge. Some masters worried spiritual conversion would lead slaves to think they were equal to Whites, fearing that “a slave is 10 times worse when a Christian than in his state of paganism,” as was proclaimed by one plantation owner.

When they did allow clergy to address the slaves, the freedom to present the gospel in its entirety was often restricted. John Dixon Long, a sincere clergyman to slaves, expressed his frustration: “They see ministers denouncing them for stealing the white man’s grain; but, as they never hear the white man denounced for holding them in bondage, pocketing their wages, or selling their wives and children to the brutal traders of the far South, they naturally expect the gospel to be a cheat.”

When summoned to family prayers, house servants would laugh among themselves after hearing the master or mistress read, “Servants, obey your masters” (see Ephesians 6:5), but neglecting to read passages that said, “Let the oppressed go free, and . . . break every yoke” (Isaiah 58:6).

That any could get past the master’s behavioral contradictions is a wonder in itself, yet many African American slaves would somehow see through the hypocrisy, grab hold of the message of personal freedom that is at the heart of the gospel, and forge a powerful transforming faith.

Anglican and Presbyterian clergy began making inroads among the slave culture of the U.S. Colonies in the early 1700s; however, their presence was too frequently monitored by the plantation owners. Sermons were encouraged to stress messages of subordination to keep slaves in line. Not all clergy saw it that way.

By his mid-20s George Whitefield, the key figure in the Great Awakening of faith that began in the mid-1700s, was the most widely known preacher in Britain. On his initial visit to the Colonies he was shocked by his introduction to American slavery. He soon wrote a widespread pamphlet, Letter to the Inhabitants of Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, which condemned the brutal physical treatment of slaves by their masters. “Your dogs are caressed and fondled at your tables; but your slaves who are frequently styled dogs or beasts, have not an equal privilege,” Whitefield chastised.

He was an early advocate for African Americans and their education, causing slave owners to be worried about his influence on their investments. In 1739 Whitefield drew large crowds of slaves to hear his preaching in Philadelphia, which brought about the advent of Black Christianity in that historic city.

Whitefield often preached in the open fields to large crowds; and his emphasis was on regeneration. He believed converted slave owners should treat their slaves humanely. His emotional sermons ignored the formality of conventional clergy and spoke to the heart of his listeners, regardless of race or standing. His themes of compassion, forgiveness, and individual regeneration struck a chord with the slaves. Despite his later failings, slaves felt an enduring connection to Whitefield and his open message.

Whitefield had been active in helping orphans and poor miners in England, and he initially planned to develop schools in Pennsylvania and South Carolina for slaves, but the desire to maintain a Georgia orphanage, “Bethesda,” supported by a large farm, became his key project. As operating costs at Bethesda mounted, Whitefield ironically became convinced that the addition of slaves, well-treated, would help sustain the orphanage. Georgia at the time was a free region and prohibited owning slaves, but in one of the great paradoxes of the 13 Colonies, he petitioned the Georgia legislature to permit slavery within its borders. He continued to advocate compassion for slaves, yet he ultimately never condemned the institution of slavery itself.

Beginning in the mid-1700s and blossoming late into that century, the Great Awakening and Second Great Awakeningthat rippled through America stressed a personal faith, personal worth, deliverance, freedom, and a more experiential type of Christianity. Mark Galli, in his insightful essay Slaves and Christianity, writes that Blacks began to swell the crowds that were coming to hear the revival preachers of the Great Awakenings. Citing that the arrival of Methodists and Baptists with their emphasis on conversion as a spiritual experience as being the key factor in the acceleration of Black Christianity.

“[The arrival of the Methodist religion] brought glad tidings to the poor bondsman,” recalled slave John Thompson as it spread from plantation to plantation.

At the age of 18, former slave Josiah Henson was struck by the words of a sermon. “Jesus Christ, the Son of God, tasted death for every man; for the high, for the low, for the rich, for the poor, the bond, the free, the Negro in his chains, the man in gold and diamonds,” Henson recalled. “I stood and heard it. It touched my heart, and I cried out: ‘I wonder if Jesus Christ died for me?’”

Baptists and Methodists encouraged converted African Americans to preach and the rise of Black preachers began a tradition of the ministry being an enduring moral force within African American communities.

By 1809 Black Methodism in the U.S. had nearly 32,000 members, while Black Baptist congregations accelerated as well to nearly 40,000 by 1813. If White society would restrict their spiritual quest of liberty and education, slaves would nonetheless pursue it with passion.

The Great Awakeningmovements and the contradiction of slavery existing in the land of the free weighed heavily in the public conscience. Some slave owners allowed slaves to attend church meetings openly and allowed some education. As the Second Great Awakeningstirred the country at the later part of the eighteenth century, revivalists such as Jonathan Edwards II openly opposed the institution of slavery itself.

It was something that many clergy during theGreat Awakening, despite their concern for better treatment of slaves, had too often avoided.

As Northern states began phasing out slavery, Black Christianity thrived in the North. In the South, slavery was still debated and remained deeply intertwined in the economy. In the decades immediately preceding the Civil War the economic explosion of the cotton industry, Nate Turner’s foiled but unnerving slave uprising of 1831, the continued slave trade within the continent, and clampdowns by plantation-driven Southern legislators only intensified the suppression of African American slaves. These were the nightmarish years of hunting down runaway slaves, the family-dividing slave auctions within American borders, the overseer’s lash, and restricted worship and gatherings.

During this period slaves held on to the hope and themes of Christianity that had been breaking through the hypocrisy of a society that continued to hold them as property. Few slaves in the South could read, but messages were passed on as music became a powerful force in sustaining the themes of deliverance they adapted. The songs became a collective refuge of shared experience in troubled times.

Through the distinctive stylings of African music and their own experience of oppression, slaves embraced the Bible’s message and made it their own. They could relate to the sufferings of Christ, the bondage of the Israelites, the promises of deliverance and redemption. The characters of the Bible became dramatically real to them as the cardinal doctrines of the gospel were preserved in song. Slaves fashioned a music “which expressed in moving, immediate, colloquial, and often magnificently dramatic terms” the restoring core message of Christianity.

This fusion of the gospel transmitted through the heartfelt, haunting songs of the slaves was a galvanizing force reverberating through slave communities. The music became their voice, their shorthand code,

the expression of toil, and the hope of deliverance. “Steal Away,” “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” “Wade in the Water”—elegant spirituals, but also laced with secret meanings.

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law raised further sympathy in the Northern states and spawned the famed Underground Railroad, a network of abolitionists and safe houses that aided runaway slaves in escaping

to Northern free states and Canada. Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, John Parker, John Rankin, William Still, Quakers Isaac Hopper and Thomas Garrett, Levi Coffin, Elijah Anderson, and other “conductors,” both Black and White, braved immense risks to lead escaping slaves to safety.

The courageous Tubman, an escaped former slave, became known as the “Moses of her people.” She was personally involved in the successful escapes of 600 slaves. It is said she would stealthily move along the edge of plantation slave quarters and communicate by softly singing “Steal Away” or a similar spiritual, indicating she was there to lead an escape group that night. A song like “Roll, Jordan, Roll” could refer to crossing the Ohio, Tennessee, or Mississippi rivers on an Underground Railroad route. “Wade in the Water,” reminiscent of baptism, would also remind escaping slaves, if they knew that the slave catcher’s dogs were closing in on them, to wade into a river or stream, thereby stopping their scent and confusing the pursuing hounds.

Meanwhile such American abolitionists as journalist William Lloyd Garrison, the dynamic former slave Frederick Douglass, and many others pushed hard for the abolishment of slavery.

Douglass, who had escaped slavery from a Maryland plantation at age 20, taught himself to read and became the most prominent, highly respected figure in the American abolitionist movement.

He was an iconic man of conviction, a tireless spokesman, writer, and lecturer, and his passion to end slavery pushed the issue to the forefront of the nation’s psyche. He had experienced the cruelty of slavery firsthand and minced no words in his denunciation of the pious hypocrisy he had experienced:

“What I have said respecting and against religion, I mean strictly to apply to the slaveholding religion of this land, and with no possible reference to Christianity proper. . . . I love the pure, peaceful, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial, and hypocritical Christianity of this land.” Frederick Douglass boldly challenged a nation to take a moral stand.

Through it all the still-young country, struggling with long-ignored contradictions that defied the language of liberty so elegantly expressed in its founding document, was heading toward the nightmare of civil war.

President Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation would legally free American slaves, but in the years that followed, the underlying cause of professed superiority over one’s fellowman would continue to raise its serpentine head to curse the ideals of liberty.

Slavery had not only rained years of horror on African Americans; it had damaged the slave masters themselves. Generations raised on prejudice, with the mind-set that somehow one man’s skin color makes him superior to another, took a toll on the conscience of a nation. The decades that followed are littered with ongoing struggle and the sickening echo of hate—the Klansmen, faces hidden behind hoods, afraid to face their own blind hate in the light of day, the numbing irrationality of Jim Crow laws and state-sanctioned racial oppression and segregation, drinking fountains marked Colored and White, voting rights suppression, job and education discrimination. Hate and insecurity hiding behind false piety, the tears and the pain.

The victories in the struggle for liberty often come with the quiet elegance of human dignity. Nonviolent, yet powerful and society-changing, they shine as beacons during the last half of the twentieth century.

1955: Rosa Parks, a young African American seamstress, commuting home from work, quietly refusing

to give up her seat to a White passenger on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, becomes the flashpoint for the Montgomery bus boycott and the great nonviolent civil rights movement that shook the conscience of America.

1957: Nine courageous teenagers, the revered Little Rock Nine, walking up the steps of an Arkansas high school amid the jeers of a hostile White crowd and breaking down the walls of school segregation in the South.

1963: Martin Luther King, Jr., a courageous young Black minister, at the historic Lincoln Memorial, addressing a crowd of 250,000 people who have marched to Washington, D.C., in support of equal rights for all citizens regardless of color. His mission is equality and peace, yet his voice thunders, “[Today] will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.”

1965: Martin Luther King, Jr., leads a peaceful march of hundreds from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to protest voting rights discrimination. Alabama state troopers and local police brutally assault the marchers with billy clubs, cattle prods, tear gas, and the trampling hooves of police horses. Though they are battered, their courage and plight touch a moral nerve in the country and lead to the landmark Voting Rights Act.

Again, the old Negro spirituals and their musical offspring were a soundtrack to freedom during the civil rights movement: ‘‘The freedom songs are playing a strong and vital role in our struggle,’’ said King.

‘‘They give the people new courage and a sense of unity. . . . They keep alive a faith, a radiant hope.”

This time, though, the Black voices were joined by thousands of White voices—the joyful noise of a nation breaking down walls of hate and celebrating true liberty. King was to lose his life for his dream of equality and freedom.

In 2013 the first African American president of the United States, Barak Obama, addressed thousands at that same Lincoln Memorial. His election had demonstrated how far the nation had come since Martin Luther King, Jr.’s stirring speech 50 years before. He urged Americans to keep vigilant in supporting the equal nation envisioned by King and the civil rights movement. “Their victory was great,” he said. “But we would dishonor those heroes as well to suggest that the work of this nation is somehow complete. The arc of the moral universe may bend towards justice, but it doesn’t bend on its own [a quote from Martin Luther King, Jr.]. To secure the gains this country has made requires constant vigilance, not complacency.”

Then on August 12, 2017: Like a bad dream jolting the country, the serpent of White supremacy surfaced again in the guise of a Unite the Right rally as neo-Nazis, the KKK, and assorted White nationalists descended upon Charlottesville’s University of Virginia, which had been founded by Thomas Jefferson. Tiki torches and the alarming Nazi chants of marchers disturbed the night air.

The following day they would be in the streets, and disaster would follow. Racism, protest, hate-filled rhetoric, ignorance, and anger swirled out of control. In the madness a White supremacist plowed his car into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer, a concerned, young White woman who had journeyed from Pennsylvania to peacefully protest the White supremacists and the climate of hate surfacing in the country. She was an active supporter of civil rights, the words displayed on her Facebook page read: “If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention.” Bodies flew into the air as people scrambled for safety; 19 people were injured in the midday maelstrom, and two police officers were killed as their helicopter crashed en route to quell the disturbance.

In the aftermath America stood numb, shocked by the climate of intolerance and false nationalism that simmers in the country. It seemed surreal that the nation whose sons had fought and died to defend liberty during World War II now heard toxic Nazi chants on its own soil. Yet it was real: a young woman and two police officers were dead. Liberty itself, after decades of toil and progress, staggered that day.

In a haunting twist of irony, back in 1965 Viola Liuzzo, a White woman and housewife from Michigan, was alarmed by the violence inflicted upon Martin Luther King, Jr.’s first aborted march

to Montgomery. James Reeb, a minister from Boston, had been unmercifully beaten and killed by racists during that event. Viola decided to travel to Alabama and support King’s march for voting rights.

Arriving in Selma, she became part of a car pool transporting civil rights marchers. While transporting

a young Black marcher, someone in a passing vehicle of Klansmen fired at Luizzo’s car, killing Viola and wounding her young Black passenger, Leroy Moton.

We had assumed such horrors were part of the past, as so much progress in civil rights equality has been made. The poisonous recent events at Charlottesville mock freedom and all who have suffered seeking it. The failure to deal adequately with racism and inequality in previous generations, allowing toxic attitudes of false superiority to coexist while we wave a banner of liberty, not only defiles the treasured ideals written in the opening words of the Declaration of Independence—it will continue to divide a nation in need

of healing, no matter how piously we disguise it.

Following the tragedy at Charlottesville, numerous photographs in the media chronicled the turmoil. A particular magazine image caught my attention: a group of racist White supremacists stood

posturing defiantly before the camera, shouting slogans and brandishing symbols that represent unspeakable atrocities that deface freedom. Despite their heavy boots and macho swagger, somehow they looked small, petty, weak, unsure, blind to the true history, ideals, and struggles that define the nation in which they live. No amount of brawn, Nazi tattoos, and the false entitlement of racial superiority

can suppress true liberty.

In reality the slaves of 1830s who sang “Steal Away” while they labored in the humid cotton fields under the gaze of the overseer, in anticipation of a secret worship service that night, thirsted for liberty. They would risk the overseer’s lash to meet in worship. The overseer thought himself piously superior, but he had to carry a whip to maintain his feelings of dominance and false security. Who was really free? True freedom knows no chains.

Illustration by Robert Hunt

Article Author: Ed Guthero

Ed Guthero has had a critically applauded career as a book and periodical designer, artist, and photographer, and a legacy ensured by years as a university lecturer. Here he shows another skill as an author. He writes from Boise, Idaho.