The Man in the Tiger Chair

Nury Turkel May/June 2023Nury Turkel was born in China, a member of an oppressed ethnic and religious minority. Today he is a Uyghur American attorney and chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, an independent government agency that monitors religious freedom violations around the world.

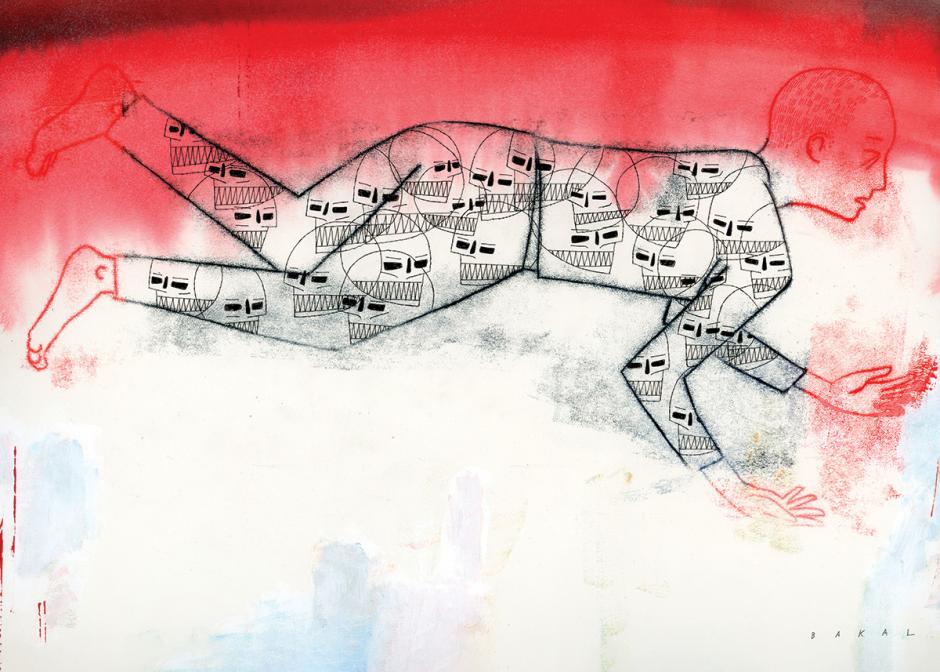

In this excerpt from his recently published book, No Escape: The True Story of China’s Genocide of the Uyghurs (Hanover Square Press, 2022), Turkel pulls back the veil on human rights abuses in China taking place on an industrial scale; abuses that are fusing high-tech innovation with age-old persecution.

In June of 2017, a Uyghur man in his late thirties sat in a Chinese police station, strapped into a “tiger chair.” He was attached to the metal chair by straps that went around his throat, wrists and ankles, so he couldn’t move an inch. To even turn his head made it hard to breathe. He had been sitting there for three days, released only for brief, closely supervised bathroom breaks.

The man knew he hadn’t done anything wrong. The police also knew that no crime had been committed. His “crime” was that he had a foreign passport, even though he had been born in Xinjiang,1 the vast, mineral-rich region in the far west of China, where the steppes of Central Asia roll out all the way to the steppes of Russia, which eventually merge with the plains of Eastern Europe. When the man had come home to visit his ailing parents, he had been automatically flagged as suspicious by the Chinese security forces.

The police asked him a lot of questions, but they already knew all the answers. Where had he lived? Who had he met? Did he have any illicit contacts abroad? He answered honestly, knowing he had nothing to hide. He had broken no laws.

Suddenly, a printer on a nearby table sputtered to life and started spewing out reams of paper. The men ignored the mechanical whir at first, but the printing didn’t stop: the machine seemed to have gone crazy. Long minutes passed as the prisoner in the tiger chair and his interrogators eyed the tsunami of paper tumbling out of the device.

Eventually, one of the policemen went over and started examining the lengthy message. He swore.

“****” he said. “How the **** are we going to find all of these people?”*

We now know, through leaked official Chinese documents, that there were twenty thousand names on the list. That summer in 2017, Chinese police officers managed to track down and arrest almost seventeen thousand of the people in the course of just ten days. The detainees—among them university professors, doctors, musicians, athletes and writers—had no idea why they were being rounded up.

Perhaps more shockingly, the police officers themselves didn’t know why they were arresting so many thousands of people. They were simply following orders that had been pre-programmed by an artificial intelligence algorithm.

The offenses that were listed sound almost cartoonish to the Western ear. They ranged from “having a long beard” to “having WhatsApp on their phone,” or “using the front door more often than the back door” or “reciting the Koran during a funeral.”

But there was nothing cartoonish about what happened to those people once they had been arrested by the Chinese authorities.

That vast roundup was the first known instance of a computer-generated mass incarceration, and its victims were almost all Uyghurs, the Turkic Muslim population whose Central Asian homeland, Xinjiang—or as we call it, East Turkistan—was handed over to Mao Zedong by Stalin in 1949, after a very brief period of independence.

Labeling almost all Uyghurs as potential religious extremists and a threat to the Communist Party’s authority, the People’s Republic of China has rounded up as many as three million of them, as well as other Muslim ethnic groups, into what it euphemistically calls “reeducation camps.”

These arrests are extrajudicial, based on an individual’s race, ethnicity and religion, the same criteria used by Nazi Germany to round up Jews and Roma. On paper, the reason given for the arrests was “de-extremification.” Since 9/11, China has used the Uyghurs’ Muslim faith as an excuse to portray the population of eleven million as potential Al Qaeda terrorists—all of them, men, women, and children.

But the real reason is this: Beijing does not consider the Uyghurs to be “Chinese” enough. The authorities perceive their centuries-old ethnonational identity, religion, and cultural heritage as disloyalty to the party and a source of future political threat to the state. Uyghurs have their own language, literature, and history, formed over thousands of years at the point where Buddhist, Manichaeist, and Muslim identities have historically overlapped. The Communist party, under General Secretary Xi Jinping, has tried to label anyone who tries to oppose China’s crackdown as “separatists” or “terrorists,” designations punishable by life imprisonment or the death penalty, just as they did with pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong and peaceful Buddhist monks in Tibet.

China’s main interest in Xinjiang is, however, the land. Located on the fringes of Central Asia’s vast steppes, the region—the largest in China, roughly the size of Alaska—contains huge tracts of natural resources and minerals (petroleum, natural gas, coal, gold, copper, lead, zinc) and long stretches of fertile agricultural land. In fact, Xinjiang produces about 20 percent of the world’s cotton supplies. To keep this supply chain going, China has assigned “work placements”—essentially forced labor—for Uyghurs to toil in these cotton fields, as well as in local factories that get contracts to manufacture goods in the West. Top brands such as Adidas, H&M, and Uniqlo have been identified as having used cotton from Xinjiang, and the US has recently announced human rights–linked sanctions against eleven Chinese companies that have supplied material or parts to Apple, Ralph Lauren, Google, HP, Tommy Hilfiger, Hugo Boss and Muji.

For the first time since the heyday of the antebellum South, cotton slavery is once again polluting the global economy on an industrial scale.

Here we are in the third decade of the twenty-first century, witnessing a population’s genocide on a massive scale. The tactics used to implement this genocide are reminiscent of Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution, but on digital steroids. Since Mao’s day, Beijing has updated its technique with an arsenal of the latest technology, much of it stolen from Silicon Valley and adapted to its own malignant purposes. The decades-long struggle over its occupation of Tibet—a cause that is largely lost in the eyes of human rights groups—helped the Chinese refine their tactics for suppressing an entire people. It became efficient at eradicating culture and independence while evoking very little protest from the world.

There is every sign that China is doing all this not just to brush aside the Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Hong Kongers but to perfect the art of digital dictatorship, a new kind of AI totalitarian state. Already, many of the spying practices used en masse against the Uyghurs are commonplace in spying on the 1.4 billion citizens of China. Their social credit system monitors ordinary people’s behavior using digital technology. Closed-circuit cameras, spying on phone apps and logging credit card information, are used to determine what is known as a person’s “social credit score,” a Black Mirror–style grading of how worthy a citizen is. Littering, buying too much alcohol—or too little, if you are a “suspicious” Uyghur, Kazakh, or other Turkic Muslim in Xinjiang—can lead to a Chinese resident being denied the right to buy a plane ticket or even to board a train. If you flee abroad and speak up, the People’s Republic will track you down, spy on you, harass you, and vanish your family into its prison camp system, or lean on your host country to send you back.

China’s ability to combine this dystopian level of AI spying with Chairman Mao–style totalitarianism is a terrifying threat. What is even more bizarre and unprecedented is the hundreds of thousands of Chinese spies sent to live with Uyghur families— often sleeping next to the family members in their cramped bedrooms. They call themselves the “Becoming Family” program, and the spies live in homes to report on suspicious Muslim-related activities. Imagine if the East German Stasi were not just spying on you but had their spies living inside your flat, pretending to be your family and using your own children to spy on you. That’s where we are in this region. Spies’ reports are fed into computers, and as a result, parents are sometimes carted off in the middle of the night to the camps, their children treated as orphans and sent off to their own Chinese “schools” where they are indoctrinated in Mandarin Chinese against their culture and their own missing parents.

As a lawyer helping Uyghurs to find refuge from this horror, and now as a commissioner on the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, I often meet with Uyghur parents who have been forced to flee their homes without being able to take their kids with them. Together, we lobby to get their children out. I sit in on the most chilling video calls: desperate mothers and fathers calling home to speak to their kids, only to see a video image of their child sitting on the knee of a Chinese cop. Quite often the children, who have been brainwashed by these officers, will act coolly toward their own parents. It’s hard to describe how heartbreaking it is to see parents, afraid they may never see their kids in person again, unable to connect emotionally with their own children.

Given the vast scale of China’s persecution, why are we not hearing more about this genocide unfolding before our very eyes? Well, for a start, the world didn’t know the full extent of the Nazi Holocaust until US and other Allied troops marched into Dachau and Bergen-Belsen in 1945. And certainly, China has banned journalists and independent observers from being allowed within miles of the camps (although it did allow Disney to shoot the movie Mulan almost within sight of a number of concentration camps).

The towns and cities of Xinjiang have been turned into high-tech military camps, with surveillance cameras and checkpoints everywhere. Trucks fitted with highly sensitive listening devices snoop on casual conversations in people’s homes, trying to pick up in private conversations what the “Becoming Family” live-in Chinese spies may have missed. China has created, in the words of one Uyghur who fled to the United States after his father vanished into the camps, “a police surveillance state unlike any the world has ever known.”

It’s extremely difficult to get accurate information out of Xinjiang. Some dedicated journalists have managed to capture glimpses of life in my oppressed homeland. And only through my own extensive links to my community and my work as a human rights lawyer have I managed to establish the contacts and the trust to lay bare what is really going on.

Some of our knowledge comes from satellite images of the sprawling camps, but a surprising amount of photographic and video evidence comes from the Chinese government itself. Having initially tried to deny the existence of the camps, it changed course when incontrovertible evidence started to seep out: Beijing released the images to try to sanitize what they were doing. It publishes carefully curated pictures of the imposing buildings, of Uyghur men in blue coveralls sitting in yards behind razor wire and with armed guards behind them. Then it says to the world, “Look, these are just normal work training facilities.” It puts out pictures of little Uyghur kids, separated from their parents in special schools where they are dressed in traditional colorful Chinese robes—red and yellow, with old-fashioned hats on—something not even modern Chinese kids wear to school.

Then there are the testimonials of those who have lived through the camps. These are Uyghurs who have witnessed torture, waterboarding, rape, and beatings. We know about dozens of women who have testified to undergoing forced sterilization in a camp before being released—what we now see is a brutal but effective effort to slash the Uyghur population. Having more than the allotted number of two children is a common cause for arrest among Uyghur women. There are only a handful of individuals who’ve managed to escape from China, and those largely because they were married to foreign nationals whose governments offered them some support. But even that support was often limited, because most governments are too afraid to offend Beijing. Some, such as Egypt’s, have even begun deporting Uyghurs at China’s request, despite their long-standing claims of “Muslim solidarity” when it came to the occupied Palestinian territories.

Despite the mounting evidence of the horror unfolding, the world continues to allow this to happen. Political and business leaders are afraid of China’s economic clout, its military strength, and its growing diplomatic muscle. Even as China frantically worked to cover up the full extent of the deadly COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan—the final death toll will probably never be known—it used its diplomatic influence to get the World Health Organization to praise its response as the “the most ambitious, agile, and aggressive disease containment effort in history,” while at the same time parroting official government figures that independent reporting has shown to be highly dubious. A couple of years ago, China even managed to arrest the head of Interpol, a Chinese citizen, and sentence him to thirteen years in jail. The world just accepted it.

Now it is herding millions of its own citizens into camps, using slave labor to bolster its economic strength, bulldozing mosques and Muslim cemeteries in Xinjiang, and building parking lots and theme parks where ancient cultural monuments once stood. Leaked documents quote Chairman Xi—who was allegedly praised by former President Donald Trump, even as the US and China were locked into a trade war over China’s theft of intellectual property, and now over the abuse of the Uyghur people—secretly calling on his minions to use the “organs of dictatorship” and show “absolutely no mercy.” Any Chinese official who fails to show sufficient ruthlessness in obeying orders risks ending up in jail themselves. As the Washington Post noted, “In China, every day is Kristallnacht.”

One truly frightening aspect of countries not denouncing China’s action is this: they might actually want to copy the lessons learned there. China’s burgeoning model of capitalism without democracy will appeal to many authoritarian rulers and will come to shape the ideological struggle of the coming century.

Already, India is building camps that can house up to two million Muslims in the state of Assam, people whom it has deemed to be noncitizens even though many were born in India or lived there for decades. It intends to hold them there until they can be deported to countries like Bangladesh, where India’s nationalist government claims they belong. Worryingly, the government intends to expand the program of mass camps to the rest of the country.

“ ‘Never again?’ It’s already happening,” Anne Applebaum wrote in the Washington Post. She is right: what was supposed to happen “never again” is now being carried out in China, and on an industrial scale.

The names in the book No Escape may sound strange to Western readers; the places might seem remote and hard to picture. But the people you will meet on these pages are real. They are normal, everyday people like you and I, unwillingly dragged into the horrors of China’s newest crime against humanity.

Terror and persecution wear people down, hollow them out. My friends say I too have aged. I can’t remember the last time I had a full night’s sleep, because the fear and anxiety gnaw at me in the darkness. Will I ever see my parents again? Who will carry my parents’ casket if they die? Will we ever meet again, as I promised them years ago? What further horrors await my people? And this time, will the world act fast enough to stop a genocide before it reaches its terrible conclusion?

Excerpted with permission from No Escape, by Nury Turkel, Copyright © 2022 by Nury Turkel. Published by Hanover Square Press.

1 Although Uyghurs refer to our homeland as East Turkistan, for the sake of consistency and ease of recognition I will use the official Chinese name of Xinjiang throughout.

*Words from original text obscured.

Article Author: Nury Turkel

Nury Turkel was born in China, a member of an oppressed ethnic and religious minority. Today he is a Uyghur American attorney and chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, an independent government agency that monitors religious freedom violations around the world.