The Other-ing

Clifford R. Goldstein March/April 2018“I was . . . thinking, . . . I’m going to go crazy. And then I saw a Marine step on a Bouncing Betty mine [designed to launch upward when triggered and explode at chest level], and that’s when I made my deal with the devil and I said, ‘I will never kill another human being as long as I’m in Vietnam. However, I will waste as many [g—ks] as I can find. I’ll wax as many [d—ks] as I can find. I’ll smoke as many [z—s] as I can find. But I ain’t going to kill anybody.’”

I grew up in Miami Beach, Florida, in the 1960s and 1970s. I lived in the northern part of the island, Surfside. Just north of Surfside, on the other side of 96th Street, was Bal Harbour. At 96th Street to the west, over a small bridge, were the two islands of Bay Harbor. Surfside and Bay Harbor, like most of Miami Beach, were quite Jewish.

Bal Harbour, home of the famous Bal Harbour shops, was an exception. Not only did no Jews live there, no Jews were allowed to. No posted sign, of course, barred Jews from buying homes there, and we Jews could freely come and go, which we often did (at 13 I even spent a few fun hours in the Bal Harbour police station). However, as I do think about it, my friends who lived there did tend to be blond-haired Aryan types, for sure.

Being Othered

Though aware that Bal Harbour was “restricted,” I don’t remember ever being particularly bothered by it. That was just the way it was. Having grown up a baby boomer Jew, with the Holocaust looming so oppressively over us, I must have just shrugged off Bal Harbour’s blip of bigotry, not realizing that, however radically different from the Holocaust, it was a mild form of the same mind frame that led to it.

In fact, what the Bal Harbour elders did, in today’s politically correct lingo, was an example of othering.

Othering can be defined as “the process of perceiving or portraying someone or something as fundamentally different or alien.” That is, othering is “identity politics,” but in reverse: instead of people singling out themselves and their religious, ethnic, sexual, and social status to form an exclusive political alliance, someone else—often with less than the best of intentions (to say the least)—does the singling out for you, defining you almost exclusively through the ethic, religious, sexual or social status that makes you different, that makes you “the other.”

In short, little did I know it at the time, but I was being othered.

A Long History

Depending upon how broadly you want to define the term, you could argue that the first case of othering occurred among those who had so much in common, two brothers, Cain and Abel. Though the biblical passages are cryptic (see Genesis 4:1-8), one could read from the texts the idea of religious conflict arising between the brothers about how they related to God in the manner of worship—a motif that has certainly extended through the ages. Whatever the ultimate issue, it led to what’s the extreme result of othering, and that is, murder.

Murder over religious differences?

Later, in Scripture, after the account of the Flood, as humans began to multiply on the earth, differences among them were more openly depicted. Genesis 10:5 reads: “From these the coastland peoples of the Gentiles were separated into their lands, everyone according to his language, according to their families, into their nations” (NKJV).1 Nations, language, family—here, in early human history, we already see the kind of divisions and distinctions that, though in and of themselves not necessarily bad, had because of human nature brought about the kind of conflict and violence that continue to this day.

As far back as recorded history goes, war—one war after another—dominated the landscape. One could imagine the sentiments, even thousands of years ago—from the ancient Sumerians to the ancient Chinese—regarding those who spoke differently, looked differently, acted differently, and worshipped differently. That is, the hostility created against the other help create the justification for war. These people are our enemies, and it’s our sacred duty to kill them before they do it to us.

And today, thousands of years later, not much has changed. Whether done by early European settlers against Native Americans, or Sunnis against Shia in the Middle East, Hutu against Tutsi in Rwanda, or the Assad regime against rebels in Syria, othering often involves the idea that the other poses a threat to oneself and one’s way of life or even existence. To mobilize a nation to send its sons to kill and be killed requires a powerful sense of othering, of making the enemy not just different but threatening.

Though people don’t, generally, kill each other because they eat with different utensils, or dress differently, Jonathan Swift, in Gulliver’s Travels, satirized what he deemed the ludicrous religious differences that led to violence in Europe in his day (he died in 1745). He wrote about two nations, Lilliput and Blefuscu, which warred against each other over which side of the egg to break, the big end or the little end.

Of course, in some cases, such as the battle against Nazi Germany, the other posed a real threat. In contrast, such as the Nazi fear of the Jews, the threats were fabricated. Whether one extreme or another, or somewhere in between, othering doesn’t have to be rational or even based on facts. It need only to paint the other in the most negative light possible. And central to the creation of the requisite negativity is the power of language.

The Language of Othering

Take, for instance, the word “barbarian.” Common in our vernacular, the term originated thousands of years ago with the ancient Greeks, who used it to refer to anyone who didn’t speak Greek, i.e., the Egyptians, Persians, Phoenicians, and Romans. The word barbarous, from which it was derived, meant “babbler,” and it arose from how these foreign languages sounded to the Greek ear, bar bar bar or the like. Though the term itself was not necessarily pejorative, given the ancient Greeks’ sense of their own cultural and intellectual superiority, negativity might have been implicit in it, anyway.

However, when the Romans (once considered barbarians themselves by the Greeks) picked up the word, it took on the connotation of primitive people outside Roman or Greek culture. They eventually applied it in a much more negative sense to the “barbarian tribes” from Northern Europe (Huns, Goths, etc.), warlike people who eventually dismantled the Roman Empire. Today, of course, the word automatically depicts excessive violence and crudity, a helpful label in the process of othering.

In the sixteenth century the British used to refer to syphilis as the “French pox,” though it also became known as the Polish disease, the Spanish disease, the Neapolitan disease, or the English disease. In each case, the idea was to blame the sickness on someone else—that is, the other.

The linguistics of othering can often be more subtle. Even a word as apparently benign as “foreigner,” from a term that originally meant (in Latin) “out of door,” came to mean “of other countries.” To say someone is a “foreigner” implies someone not from us, not from here, someone different. It is, even if meant innocently, a subtle form of making a distinction between oneself and the other.

Dehumanizing

Of course, it’s one thing to make a distinction between “us” and “them,” with the “them” being another people group defined by their differences—gender, ethnic, religious, political, whatever—from us. Whatever the differences, they are still humans and, as such, deserving of basic “human” rights.

But what if they are not “human”? That is, othering degenerates to a whole new level when the distinction becomes so great that the other is seen as subhuman, nonhuman, or even as animals. This transition can happen easier than one might think, too.

In his The Vietnam War: An Intimate History, Geoffrey Ward quotes one Marine: “I was . . . thinking, . . . I’m going to go crazy. And then I saw a Marine step on a Bouncing Betty mine [designed to launch upward when triggered and explode at chest level], and that’s when I made my deal with the devil and I said, ‘I will never kill another human being as long as I’m in Vietnam. However, I will waste as many [g—ks] as I can find. I’ll wax as many [d—ks] as I can find. I’ll smoke as many [z—s] as I can find. But I ain’t going to kill anybody.’”

Of course, this example could be dismissed as an emotional overreaction to the stress of war, a spontaneous one-off as opposed to a systematic and deliberative process to dehumanize an entire group. Unfortunately, history reeks with numerous examples of the latter, the systematic dehumanizing of people groups—the most vile, extreme, and dangerous form of othering.

In the antebellum South, African slaves were deemed three-fifths persons; true, it was for political purposes (counting them for congressional representation) but clearly an example of, if not total dehumanization, then at least three fifths of the way.

In 1907 Indiana was the first American state to legalize compulsory sterilization for the “unfit.” Wrote one advocate for the sterilization law: “Society must protect itself; as it claims the right to deprive the murderer of his life so also it may annihilate the hideous serpent of the hopelessly vicious protoplasm.”

Hopelessly vicious protoplasm?

Sterilization isn’t the same as mass murder (even if a potential step in that direction), which happened on a large scale in the past century, the most horrific example being the Holocaust. Building on centuries of anti-Semitism, the Nazi propaganda machine turned the victim, at least in the mind of the perpetrators, into something less than human.

“The Nazis,” wrote David Livingstone Smith in Less Than Human, “were explicit about the status of their victims. They were Untermenschen—subhumans—and as such were excluded from the system of moral rights and obligations that bind humankind together. It’s wrong to kill a person, but permissible to exterminate a rat. To the Nazis, all the Jews, Gypsies and others were rats: dangerous, disease-carrying rats.”

The Other

Othering, in one sense, is natural. We exist as individuals, and no matter how cohesive any group we belong to, we still distinguish between ourselves and others. And, of course, we at times will find ourselves in opposition, or even conflict, with others—regardless of how close they might be.

It all depends upon degree and context. Homo homini lupus goes a Latin proverb (“A man is a wolf to another man”). For philosopher Michel Foucault, othering is all about power and control. We other others in order to make ourselves seem better than they are, and that, in turn, justifies our dominance over them.

An example of what Foucault talked about comes from ancient Greece. In Plato’s Republic Socrates argues that the people, hoi polloi, need to be told that some among them, a minority, were born by God of gold, the rulers; others were born of silver, the auxiliaries; others were born of iron and bronze, the farmers and craftsmen. This form of othering would help maintain social cohesion by keeping each group in their place; that is, it would help those in power maintain that power by keeping the others satisfied on their rung in the hierarchy, especially if it were what the gods had ordained. Similar thinking, argued Foucault, was central to the justification for colonialism: we colonialize these people in order to make them better, in order to make them more like us. (And if we can get rich in the process, so much the better.)

Othering doesn’t, however, always have to be negative. Philosopher Emmanuel Levinas built a philosophy on the concept of “the other,” but sought to extract from it an ethic of responsibility and obligation, especially when the other needed our help. His idea could be expressed by a Jewish proverb: “The other’s material needs are my spiritual needs.”

If only . . .

Othering in the Age of the Internet

A powerful irony has unfolded in recent years in regard to othering. For most of history, without modern means of travel or instant communication, the vast majority of humanity lived isolated from the other, if the other meant divergent people groups. Most of the masses never traveled far, and those among them who most likely would travel—soldiers—often did so in order to kill the people whom they met. It’s not hard to imagine how mysterious, different, even “dangerous” (given the right propaganda), the other would appear to people who never traveled more than 25 miles from the family farm or from the city walls.

Today, though, with instant communication, with astonishing means of travel, human interaction with the other takes place on an unprecedented scale. The other can now be, instantly and easily, near. And yet, has all this interaction, this closer realization of the “global village” idea, created a greater sense of shared commonality? Ironically, no. Othering appears to have only worsened. At the risk of a cliché, familiarity breeds contempt seems apt in our digital age.

“At any given moment,” wrote Gore Vidal, “public opinion is a chaos of superstition, misinformation, and prejudice.” And today this same public opinion is exponentially fed more of this superstition, misinformation, and prejudice through digital technology.

Facebook, for example—where one could share recipes, photos of the grandkids, and pictures from the ski vacation—has morphed into fertile ground for egregious othering. The problem isn’t with the medium, but with those who use it; and however good his intentions, Mark Zuckerberg can’t police 2 billion monthly users.

And, now, as immigration, terrorism, and identity politics suffuse cyberspace and, hence, our consciousness—we all need to be more careful about othering, even if meant innocently. The distinction made between “us” and “them” rarely happens, without, even subconsciously, “us” being pitted against “them.”

The Solution?

In principle, the answer to the problem of othering isn’t hard. As Jesus said: “Do to others as you would have them do to you” (Luke 6:31, NIV).2 We could, in this context, paraphrase it slightly like this: “Do to the other as you would the other do to you.” Easier said than done, of course. For, to quote another Bible text: “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: who can know it?” (Jeremiah 17:9).

In short, given human nature, and the tendency to automatically relate better to those who are most like ourselves, othering—in one form or another—is not going to disappear anytime soon. Which means, then, that maybe the most we can hope to do is be aware of it, not just in different people but in ourselves, and seek to minimize the damage by focusing not on our differences but on our commonalities, which (if we think about it) are much greater than the things that set us apart, even in Miami Beach.

1Bible texts credited to NKJV are from the New King James Version. Copyright © 1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

2Bible texts credited to NIV are from the Holy Bible, New International Version. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

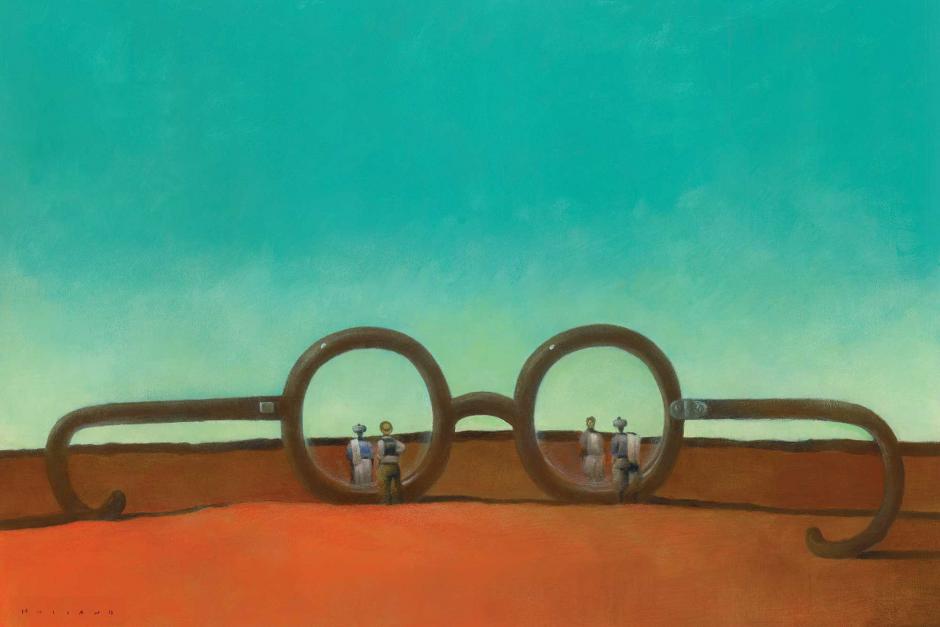

Illustration by Brad Holland

Illustration by Brad Holland

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.