Thou Shalt Not Lie

Marc Zvi Brettler July/August 2023The myth of the Ten Commandments

Asked to name the Ten Commandments in a 2006 appearance on “The Colbert Report,” Congressman Lynn Westmoreland, co-sponsor of a bill that would have required the Ten Commandments to be displayed in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, responded: “Ummmm. Don’t murder. Don’t lie. Don’t steal. Ummmm.” He then admitted, “I can’t name them all.”

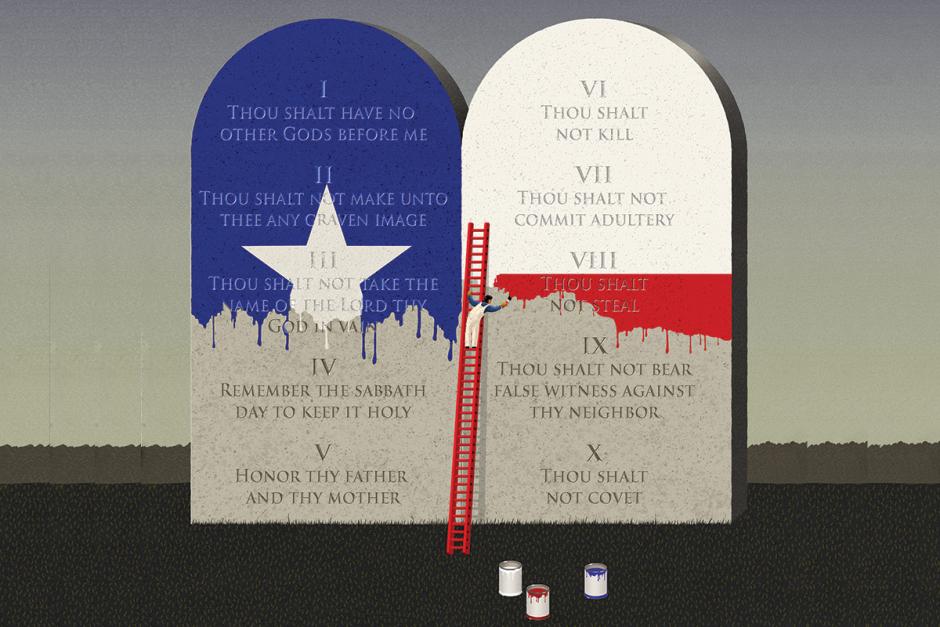

The State of Texas recently considered a law mandating that a particular form of the Ten Commandments be posted in every public school classroom; although it did not pass yet, it will likely be reconsidered in a future session, and similar bills are being considered elsewhere. The Texas bill is especially problematic, and violates the commandment that Westmoreland mistakenly attributed to the Ten Commandments: “Don’t lie.”

Biblical scholars agree that there is no distinct biblical text that can be identified as “The Ten Commandments.” The phrase “the Ten Commandments” appears in the King James Version of the Bible in Exodus 34:28 and Deuteronomy 4:13 and 10:4. The Deuteronomy texts refer to the regulations in Deuteronomy 5:6–18—one rendition of the Ten Commandments. But the referent in Exodus is unclear, since the Exodus version of the Ten Commandments appears many chapters earlier, in 20:2–17, and Exodus 34:28 may refer to a different set of ten laws found in Exodus 34:11–26.

Furthermore, the commandments in Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5 are not identical. They differ in minor respects, sometimes more obvious in Hebrew than in English. They diverge in larger matters as well, including why the Sabbath day should be observed. Thus, there is no such thing as “the” Ten Commandments: the Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5 versions differ in details, while Exodus 34 may refer to ten quite different commandments! And to complicate matters further, the text found in several Dead Sea Scrolls, ancient biblical translations, and the New Testament differs from the standard Hebrew texts of Exodus and Deuteronomy.

The Texas bill mandates that a particular version of the Ten Commandments be posted, a form that does not follow Exodus 20 or 34, or Deuteronomy 5. It is a highly problematic version of the Ten Commandments made up by the Fraternal Order of Eagles in the 1950s as part of their Ten Commandments campaign. On what basis can they, or the state following them, decide how to abridge such a central document and how to translate it into English?

Like any biblical text, the Ten Commandments present the translator with many choices and problems. These begin at the very outset, where the Hebrew allows for two translations: “I am the LORD your God” or “I, the LORD, am your God.” This is a subtle but important difference. The difficulties are less subtle later on; where the Texas version bans killing, biblical scholars find a prohibition against murder. I do not see how a legislative body—or if it is appealed to, a court—has the professional knowledge to arbitrate between alternative translations.

Additionally, the Texas proposal lays out the Ten Commandments in a problematic fashion, as twelve distinct sentences. The Bible itself does not number them, and contains thirteen statements that could be combined in different ways to reach ten; various religious traditions and scholars use different methods to attain ten commandments. But which is right? And is it not odd to mandate a poster that must begin with “The Ten Commandments” and then follow it with twelve statements? Math teachers might not be happy to have this Ten Commandments poster in their classrooms.

Furthermore, I also object to the Texas bill as a Jew. The term “Ten Commandments” suggests that what follows are indeed commandments; and in many religious traditions, the first saying is the commandment: “You shall have no other gods beside me,” with “I am the LORD . . .” serving as an introduction. But within Judaism, “I am the LORD” counts as the first. But it is not a commandment! Thus, the term “commandment” is alienating to the Jewish community, and I prefer to call this text “the Decalogue,” from the Greek, which means “the ten sayings.”

The proposed Texas version of that first “commandment,” following the Fraternal Order of Eagles, presents additional difficulties to my community. It reads: “I AM the LORD thy God.” But what of the rest of the verse, “who brought you out of the land of Egypt, the house of bondage”? This depiction of a liberator God is a central Jewish image, commemorated often in Judaism, most especially on Passover. Can these words be removed by legislative fiat? And to raise another issue: Can they apply to every student studying in a Texas classroom?

The mandated posting of the Ten Commandments sparks other significant problems for students who do not have this text as part of their Scripture. Should we legislate the posting of any theistic statement in all classrooms? Should we subject children whose practice includes worshiping G/god(s) using images to their classmates’ derision by posting, “Thou shalt not make to thyself any graven images”? And finally, the Decalogue endorses vicarious, intergenerational punishment (Exodus 20:5; Deuteronomy 5:9); do we want to endorse that idea by placing the Ten Commandments in every classroom?

I fully agree with Pastor Thompson in his article (p. 11): The religious person should embody these commandments through practice rather than a public display of piety. And Dr. Russo’s warnings are equally trenchant (p. 7). He raises the issue of the Supreme Court’s new criterion of “reference to historical practices and understandings,” a tenuous and ambiguous standard—much less clear than the Lemon standard it replaces, and I worry whether the courts have the ability to adjudicate such historical issues in a fair and unbiased fashion. The recent coronation ceremony of King Charles III and Queen Camilla was full of quotations from the Hebrew Bible (especially Psalms) and the New Testament, and offers an indisputably certain example of a tradition heavily based on the Bible. The coronation ceremony illuminates by contrast how much less significant biblical influence was on American history and tradition.

So, let’s not lie. There is no such single thing as The Ten Commandments—in Hebrew, and especially in English. The Texas version is a complete fabrication. And let’s not perpetrate the lie that America was always a deeply biblical religious society based on the Ten Commandments. Let’s keep the Ten Commandments—in their multiple versions—where they belong: in our Bibles rather than on our school walls.

Article Author: Marc Zvi Brettler

Marc Zvi Brettler, a member of the American Academy for Jewish Research, is the Bernice and Morton Lerner Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies in the Department of Religious Studies at Duke University. He is author of numerous books and articles, including How to Read the Jewish Bible and The Bible With and Without Jesus: How Jews and Christians Read the Same Stories Differently (with Amy-Jill Levine). Brettler is co-editor of The Jewish Study Bible and The Jewish Annotated New Testament, and he co-founded TheTorah.com, which is dedicated to making academic biblical scholarship available to the wider public.