Unholy Alliances

Bettina Krause March/April 2024An interview with filmmaker Dan Partland.

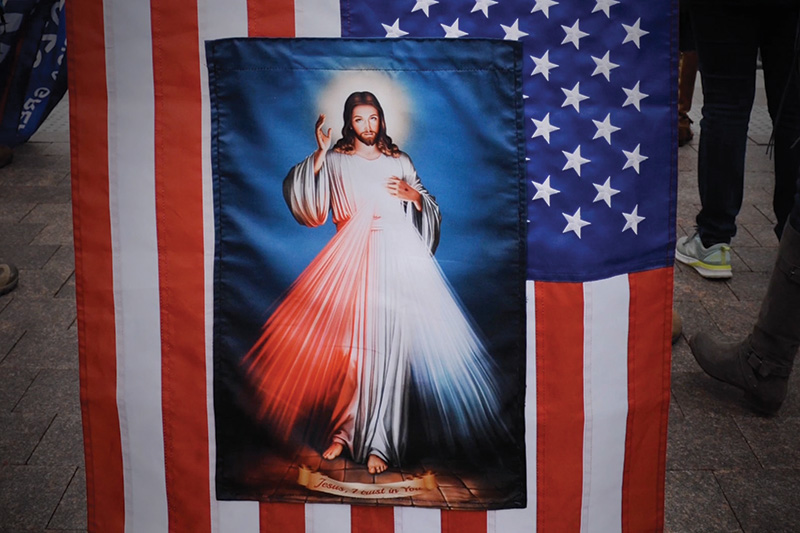

The documentary God & Country, currently showing in theaters, has split opinions among American Christians. It’s a 90-minute, emotionally intense exploration of one of today’s least understood and arguably most subversive political movements, Christian nationalism. It features 18 high-profile Christian thinkers and leaders—from David French, a New York Times columnist, to Russell Moore, editor of Christianity Today.

The film is based on a 2020 book written by investigative journalist Katherine Stewart, The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous World of Religious Nationalism. Its executive producer is well-known Holly wood actor and producer Rob Reiner and it’s directed by Dan Partland, a veteran documentary filmmaker who has twice won the Emmy for Best Nonfiction Series and been twice nominated Nonfiction Producer of the Year by the Producers Guild of America.

Bettina Krause, editor of Liberty magazine, recently talked with Mr. Partland about the ideas that shaped God & Country, and what he hopes the film achieves.

Bettina Krause: What first attracted you to this topic?

Dan Partland: I very much came to this project from a secular perspective—concerned for what I saw going on in our politics and concerned for the state of American democracy. But as I dug into it, I learned a lot from the faith community. I learned that Christian nationalism also represents a danger to not only religious freedom but to faith communities themselves. It’s tearing churches apart. It’s tearing families apart. And there’s a tremendous pressure on pastors to get on board with preaching political messages. A lot of pastors are just trying to hold their congregations together, but their members are stuck in information silos, being exposed to the same messaging over and over again.

Krause: For someone coming from a secular perspective, you clearly know a lot about what’s happening inside American churches! Did you already have some background knowledge when you started out?

Krause: For someone coming from a secular perspective, you clearly know a lot about what’s happening inside American churches! Did you already have some background knowledge when you started out?

Partland: No, not really. I mean, I was raised in a secular home but in a multi-faith extended family—a classic American family. My first cousins include Presbyterians, Catholics, atheists, Jews, and Greek Orthodox. So literally none of my first cousins share a faith with the other. For nearly 250 years of this country, we’ve really celebrated this kind of religious diversity as a unique and defining feature of American life. But then somehow, here in 2024, a huge portion of the population has turned against that foundational American idea.

So yes, I think I have acquired some expertise along the way because I’ve been so deeply embedded in this material. It does require getting out of your own silo. And everyone is in an information silo; we have to accept that. If you want to learn about others, you have to get out of that silo—both in the digital realm and in the real world. And when I did, I was just absolutely astonished at what I found. I realized, also, that I had to be a quick study—to acquire a lot of sensitivity. Because talking about people’s faith is such a sensitive thing.

Krause: I’ve interviewed different academics and authors about Christian nationalism. These are people who’ve done the research, crunched the numbers, analyzed the trends, and written books and papers. What unique opportunities does documentary filmmaking, as a medium, bring to the table in terms of engaging with this topic?

Partland: Well, it brings narrative storytelling and emotional depth to a subject that otherwise can be abstract or difficult to understand. There’s no shortage of excellent reporting and scholarship about this phenomenon. There’s headline after headline in major publications. But somehow it’s not bringing the issue to life in a way that the public can understand.

Also, most people aren’t going to do a deep dive into the issue and read the books that have been written by the experts we talked to in the film. So the goal of the documentary is to distill some really important central ideas from all this great scholarship, to put it into a coherent narrative, and to deliver the emotional import that I think is missing from a lot of academic work. To bring it home in a concrete way that regular folks can understand.

Krause: You mentioned earlier that this subject is sensitive. And it is sensitive to those of us who claim the name “Christian.” And especially when Christian nationalism is given its full description, White Christian nationalism. How did you, as a filmmaker, factor in that sensitivity? What was your plan for making sure that didn’t get in the way of your overarching message?

Partland: You’re right, it’s a terrible, terrible name. White Christian nationalism. It’s a terrible entry point for the film. Why would anyone who bears the identity of White or Christian—or even, nationalist, in the sense of having national pride or patriotism—why would they want to engage in this conversation?

So that was one of our central problems in talking about this subject. One of the things the film had to do was to start by showing what Christian nationalism really is—showing that it’s not patriotic in any American sense, and just as importantly, that it’s not Christian in any sense. Christian nationalism is a political identity, not a faith identity. One of the ways it thrives as a movement is by successfully confusing people into conflating their political identity with their faith.

Krause: Defining Christian nationalism can be difficult, though. There are shades and degrees of bringing your faith into the political space. For instance, when a Christian goes to vote, they shouldn’t have to leave their faith behind, right? Is it Christian nationalism to vote or advocate for public policy preferences that are informed by your faith?

Partland: Well, people’s faith inevitably informs their political choices, and it should. The important distinction—and it can be quite hard to separate the two—but the important distinction is whether you’re voting consistently with the values of your faith or whether you’re voting to enshrine your faith into law.

Let me put it this way. Martin Luther King was, of course, very political. And nobody could say that he left his faith outside of politics. When he made the argument to the mainstream public against segregation and for civil rights he didn’t say, ”We need to do this because my faith says so.” He said, ”We need to do this because we believe in equal justice and human dignity.” Those are values that can also be applied to our politics.

But when we start to work politically to put Christian faith into American law, that runs afoul—not just of basic democratic norms—but also runs afoul of the anti-majoritarian rights that were written into America’s constitution. That was the brilliance of the founders. They always understood that for us to have religious liberty, minorities needed to be protected against the tyranny of majorities.

What Christian nationalism ultimately tries to do is to create two classes of people. There’s the White Christians—who this country is really for—and there’s everyone else. And the opinions of the White Christians are more important than everyone else’s. But as soon as you have two classes of people, even with just subtle distinctions between classes, you don’t have democracy. You have tyranny.

Krause: How much do you think fear plays into this whole dynamic? For Christians, fear of cultural marginalization, fear they’re being pushed to the edges of society?

Partland: I think grievance in general is what’s shaping our politics right now. I think there’s been a concerted effort to whip up fear and anger in Christian communities and to stoke fear of Christians being marginalized. And it’s become so commonplace to speak in those terms that it’s become an accepted norm that Christians in this country are marginalized. But this is where you need to actually look for evidence. And there just simply is no evidence whatsoever that Christians are marginalized.

What I do think is happening, though, is that Christians are losing both cultural and political power just by virtue of a trend towards secularization. This isn’t really about religious liberty. But when you’ve been privileged for a very long time, the loss of cultural power can feel like marginalization.

Saying Christianity is under threat is a valuable way to fundraise and to activate voters. If you can convince a voting bloc that they’re in that much danger, you can get them activated.

Krause: When the movie trailer for your documentary came out a few months ago, you got a lot of blowback from some in the evangelical community—and so did the Christian academics and leaders involved in the documentary. Did that surprise you?

Partland: First of all, I got some blowback, but the blowback I got isn’t really that important. What was very concerning to me was that the participants in the film got a lot of blowback.

It was telling, I think, that those participants with the strongest conservative Christian bona fides got the most criticism. Basically, a Christian nationalist mob went out to discredit them. It showed just how concerned these Christian nationalists were about being exposed. It’s a weak ideology if, when it’s exposed to criticism, its instinct is to personally discredit the critic.

Krause: One of the comments I’ve heard more than once about your documentary is along the lines of “Why should we listen to a critique from a Hollywood liberal?” Rob Reiner has been a prominent part of this project as executive producer. What role did he play and has his involvement been an asset or a liability?

Partland: Well, Rob was instrumental in getting the project started, but then he stepped into the background and he wasn’t part of the editorial shaping of the content. He was very, very valuable to me late in the process when he came back into the mix as an artist and a craftsperson. I could show him the film and he could say, ”Here’s where it drags. Or, this communicates really well to me. Or, I don’t understand this point.”

Whether he’s been an asset or liability to the project? He’s been both. The reason he initially didn’t want to be involved in the project, other than to get it started, was he didn’t want to be a distraction from the content. But what we have learned along the way is that his attachment is a distraction, but it’s also causing people to take note of the project. It creates an interesting vantage point that’s helpful in publicizing the film.

Krause: Religious nationalism isn’t just happening here in America. We’re seeing ethno-religious nationalism in India, Russia, even places like Brazil, Poland and Hungary. Is there anything that makes American Christian nationalism distinct? That gives it a unique American flavor?

Partland: Yes, absolutely religious nationalism is happening elsewhere. The most concerning part of all of this is that there’s a widespread belief among American Christians that the United States itself plays a messianic role in history, in human history. And if you believe this, if you believe that the United States has a God-ordained role to play in human history as a Christian nation, you can convince yourself to do just about anything in order to make sure that God’s will is done.

Krause: You’ve spoken elsewhere about the many, many Christians who aren’t Christian nationalists, but they’re vulnerable to its messages. How do you hope your documentary hits them? What do you hope that they’ll take away from it?

Partland: Well, I think we have to be realistic about what a film can do. You are always reaching a coalition of the willing. There will be people who don’t want to hear these ideas and they’re not going to see the film.

But I think we’re starting a conversation that’s reverberating around media, and it’s reverberating within families and between friends. People who’ve seen the film are sharing the film with others, and we’re encouraging people to use it in exactly that way. It’s probably not a tool that’s going to reach somebody who has fully gone deep into Christian nationalism. But the vast majority of people are in more moderate, reachable places.

You can, say, ask someone you love, “Would you watch this film for me?” It isn’t about listening to some atheist person or secular person or Hollywood elite. It’s not about listening to me. It’s about listening to the people in the film. We’ve collected the very best voices for audiences to hear and use—I learned so much from them. I mean, if you were sitting down at a table with a relative you thought was being unduly influenced by Christian nationalist forces, wouldn’t you like to have Russell Moore, or David French, or Katherine Stewart sitting alongside you and doing the heavy lifting?

That’s what the film was made to do. I hope, at the very least, it starts a conversation among the faithful about the fractures being caused within the American church itself. And more than anything, I hope that the film reconnects everyone—all of us—with some core American values. And the separation of church and state is really one of the most iconic American values—it’s the genius of our secular system of government. It’s the way we’re able to protect everybody’s religious liberty.

Article Author: Bettina Krause

Bettina Krause is the editor of Liberty magazine.