Universalizing Support for Religious Liberty

Alan E. Brownstein September/October 2017During the past 30 years, with a few exceptions, the Supreme Court has interpreted the religion clauses of the First Amendment to mean as little as possible. The Court seems content to enforce a minimalist, formalistic understanding of both the free exercise clause and the establishment clause. Constitutional prohibitions will invalidate overt discrimination against religion through regulation or funding. Neutral regulations and neutral conditions accompanying funding will be grist for the political mill.Under this doctrinal approach, most church-state disputes will be resolved through political deliberation rather than constitutional adjudication. For the foreseeable future, religious liberty and equality will depend on the political judgment of the polity.

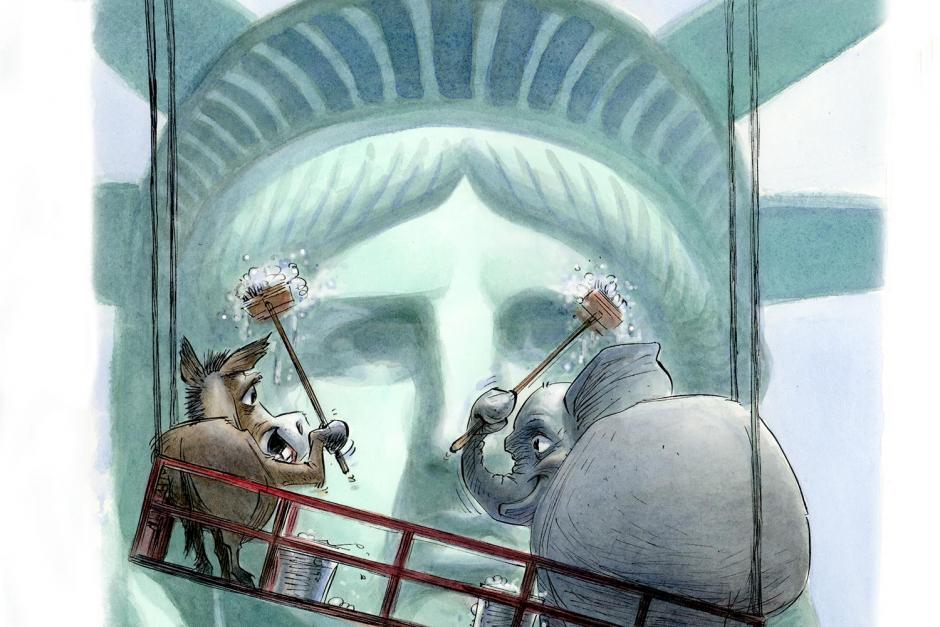

This means that for religious liberty and equality to flourish, proponents of these rights need to develop a broadly accepted political consensus to support them. That consensus does not exist today. Religious liberty and religious equality have become polarized, politically partisan issues with progressives and Democrats and conservatives and Republicans frequently on opposite sides of the battles lines. As a liberal, I am most familiar with the reasons that support for religious liberty has declined on the left side of the political spectrum. In this article I want to describe some of the conflict areas and the problems that need to be overcome if we are to move forward toward an increased commitment to religious freedom of conscience.

Conflict 1

Speaking generally, progressives believe that whatever protection religious liberty receives has to be universal and extended to people of all faiths. It cannot be reserved for only certain religions or beliefs. Progressives also strongly support religious equality principles. Government must treat people of all faiths as if they are of equal worth and deserving of equal respect. Right now, progressives believe that many conservativessupport religious liberty only for the adherents of certain faiths and reject religious equality as a political good. This mistrust of conservative intentions is a formidable barrier to political consensus.

In this regard, President Trump’s executive orders restricting the entry into the United States of foreign nationals from several countries with populations that are overwhelmingly Muslim, often referred to as a “Muslim ban,’ and the endorsement it has received from the president’s supporters, has been an unmitigated disaster.There are important and complex constitutional questions raised by these orders: questions relating to the propriety of invalidating legislative or executive action based on the motives of the decision-maker and to the degree of deference due the national government on immigration matters. But those issues are tangential to the core inflammatory nature of the orders and the rhetoric used to defend them.

A foundational premise on which establishment clause doctrine is based is the rejection of religious preferentialism. Government cannot favor certain faiths over others. Even more critically, out of concern for both establishment clause and the equal protection clause values, it cannot single out people of a particular faith for discriminatory treatment. These commitments, like all constitutional commands, reflect what we have learned as a people over our 225-year history.

We know that religious prejudice has often been intertwined with ethnic bigotry. Throughout American history religious intolerance and nativist nationalism worked hand in sordid hand.Contempt for Native Americans as an ethnic group was reinforced by contempt for Native American beliefs. Prejudice against the “heathen Chinese” speaks for itself. Discrimination against the Irish reflected anti-Catholic bigotry. Anti-Semitism juxtaposed religious animosity with ethnic prejudice against East European immigrants. The connection between ancestry and faith in our history undermines any suggestion that territorial bans can be viewed as entirely neutral and divorced from the religious demographics of the countries singled out for discriminatory treatment.

Further, and of greater importance, a commitment to religious, ethnic, and racial equality rejects categorically the suggestion that entire groups can be singled out for discriminatory treatment because of the real or imagined wrongdoing of individuals. Collective scapegoating is the kindling of race riots and pogroms. It was the foundation for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, a taint on American democracy disgracefully vindicated at the time by the United States Supreme Court. Throughout American history, parents of racial, ethnic, and religious minorities expressed the same fearful prayer to their children whenever a notorious crime was committed. Please do not let this wrongdoer be one of us—for all of us will be blamed for his transgressions.

The rejection of the identification of entire groups as threats or potential wrongdoers is a bulwark for the protection of minorities in our society. Any government action that comes close to crossing this line of defense must move forward only after the most careful scrutiny of its justifications. To capriciously issue an order directed for all intents and purposes at a particular religious group is fundamentally unacceptable. To progressives, conservative support for the president’s order can reflect only a complete repudiation of religious equality as a constitutional principle or political norm.

Progressives also see a lack of commitment on the part of conservatives to protect the religious liberty of Muslims. To be sure, this perception may be exaggerated. But there is so much smoke here that it is difficult to ignore. I recall, for example, speaking on a panel at a national meeting of a conservative legal group some years ago. In response to a question, I suggested that it should be constitutionally and normatively unacceptable for government agents to infiltrate mosques and record the statements of clergy and congregants without any showing of cause to believe that unlawful conduct or violence was being incited or planned at particular Muslim houses of worship.To my astonishment, I discovered that virtually everyone who spoke to me after the session disagreed with my argument. Muslims were different, and different rules had to apply to this religious community. (The only person who supported my position was a man from Poland who described how the Communist government had regularly tried to infiltrate Catholic churches in his country.)

Nor is a perceived lack of conservative support for religious liberty and equality limited to the Muslim community. In Town of Greece v. Galloway the Supreme Court upheld a town board’s practice of beginning each meeting with a sectarian prayer offered by invited Christian clergy who often asked the audience to stand and bow their heads while a prayer was offered in their name. There was not even the semblance of any regard for religious equality in the town’s proceedings. Non-Christian residents were treated as if they did not exist or were entitled to no recognition or respect. Further, it is intrinsically coercive for residents to be asked to stand and join in a prayer by state-selected clergy before addressing the board in an attempt to attempt to influence its decisions on local issues. Yet neither the conservative justices joining the Court’s opinion nor the many amicus briefs submitted supporting the town paid scant heed to the substantial burden on religious liberty the town’s practice imposed on religious minorities and nonreligious residents. Progressives, like me, who strongly support religious liberty, experienced the failure of conservatives to recognize and challenge the abridgment of religious liberty in Town of Greece as a stunning abandonment of the principle that religious liberty must be protected universally for everyone.

Conflict 2

During the past two or three decades, many religious liberty conflicts have focused on issues relating to gender, sexuality, sexual orientation, abortion, and contraception. In the great majority of these cases, religious liberty interests were aligned with conservative political interests. During this same period there has been a decline in support by progressives for religious exemptions and accommodations—particularly for broad-based religious liberty statutes such as federal RFRA and state RFRA laws. There have been exceptions to this decline in support. California, a very blue state for example, passed a Workplace Religious Freedom Act that substantially increased the duty of employers to accommodate the needs of their religious employees. But for many progressives, religious liberty is increasingly seen as less like a shield used to protect minority religious practices and more like a sword, a weapon used to damage the rights of others.

Some of the reduced support for religious liberty rights here is understandable. Such rights as religious liberty or freedom of speech are easy to support when the exercise of the right costs little and harms no one.There could be universal support for protecting the right of Native Americans to use peyote in religious rituals because there was no significant state interest justifying the refusal to grant a religious accommodation in that case. The political dynamic changes when the cost of rights increases. Rights can be expensive political goods. The exercise of the right can impose real burdens and harms on third parties. When the price of protecting a right increases, it is hardly surprising that those persons who will bear the cost and experience the resulting harm, and their political allies, will question whether the right is worth protecting in such circumstances.

I respect and share the concerns expressed about the cost of protecting religious liberty in cases involving exemptions from civil rights laws, for example. But these hard cases do not typically undermine and jeopardize our commitment to protecting a right. Many of us may struggle to resolve difficult free speech cases, in which expression imposes costs and harms on third parties, but continue to endorse the rigorous protection of freedom of speech. Why then does there seem to be a withdrawal of support for religious liberty in general rather than the recognition that there are some hard cases in which the cost of protecting a right should be determined to be excessive and unacceptable?

I suspect that part of the reason is that some progressives do not see how religious liberty provides protection of the values they endorse. From their perspective, conservative groups whose values are at risk assert and benefit from religious liberty claims, and women and members of the LGBT community bear the resulting costs and suffer the resulting harms. Freedom of speech has utility for all sides in our polarized society. Religious liberty appears to be a limited weapon available to only the right side of the culture wars.

This focus on contemporary conflicts is understandable, but it is also misleading. Religion has been part of the foundation for progressive political arguments throughout American history, from the abolitionists’ crusade against slavery, to campaigns for the poor and workers’ rights, to the civil rights movement, and to various anti-war movements. These arguments were not always couched explicitly in religious liberty terms, but religious beliefs strongly influenced the positions progressive advocates asserted. It is a mistake to ignore the importance and power of religion to promote liberal ideals.

The one-sided alignment of religious liberty and conservative politics is slowly starting to shift. The political left is responding to the religious liberty claims of the Muslim community discussed earlier. The current administration’s distain for the rights of Muslims is a reminder that the defense of religious liberty is a necessary foundation of America’s distinctive commitment to religious pluralism.

Even more dramatically, the religious left is reminding both secular and religious progressives that Jewish and Christian beliefs offer a stark repudiation of the administration’s refugee, immigration, and deportation policies. Religious requirements of compassion, mercy, and justice extend beyond national borders. No command is repeated more often or emphatically in the Jewish Bible than the admonition “You shall not wrong a stranger or oppress him, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” Churches and synagogues throughout the country are challenging oppressive policies and designating themselves as sanctuaries for the “strangers” in our communities. If the national government demands that local government officials and private individuals and institutions facilitate and assist in immigration and deportation policies in violation of religious conscience, it would not be surprising if individuals and institutions assert claims for exemption and accommodation under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Other policy challenges from the left side of the political spectrum will also resonate with religious belief. Surely one may argue that national health care legislation resulting in a loss of health insurance coverage for millions of Americans, many of whom are poor or already ill or disabled, conflicts with religious obligations to care for those who are needy and helpless. As progressive voices recognize that many of their values are grounded in and resonate with religious beliefs and that religious liberty applies to both conservative and liberal believers alike, the reality that religious liberty is a universal good may receive more respect.

Conflict 3

There seems little doubt that establishment clause constraints on government funding of the secular activities and perhaps even the religious activities of religious institutions are being repudiated by the current Court. Indeed, the Trinity Lutheran Church v. Pauley case, recently argued, suggests that state and local government may be constitutionally prohibited from excluding grants to otherwise-eligible religious applicants from neutral funding programs.

The obvious danger to religious liberty that state funding creates has long been recognized. By accepting government funding, religious institutions will be at increased risk of government interference with, and control over, their activities. As the colloquial saying goes: “He who pays the piper calls the tune.” What may not be fully appreciated is the degree to which funding proposals that treat religious institutions and their secular counterparts as equivalent, fungible providers of public services dramatically undermine the political arguments for religious institutional autonomy and exemptions from general regulations. The unwillingness of progressive or secular groups to accept accommodations and exemptions for religious institutions increases exponentially when the religious institution receives government funds—and the rejection of accommodations reaches its zenith when the government funds support the very activities for which an accommodation is sought.

Government funding raises three problems for the defense of religious institutional freedom. First, there is a powerful presumption (at least among progressives) that public funds should be used for public purposes. If people of all faiths are taxed to fund a service, it does not matter whether the service is provided directly by a government agency or indirectly through a private religious or secular conduit. The service should be available to all eligible beneficiaries of the service, regardless of their faith, sexual orientation, gender, or ethnicity. And the same argument applies to the hiring of employees to staff government- funded programs. Discrimination in hiring is unacceptable. No institution using government funds should have the religious freedom to discriminate against protected classes in providing subsidized services or in hiring employees to staff subsidized programs.

General liberal antipathy toward discrimination against protected classes can be countered with considerable success when religious institutions reserve their own resources for the hiring of employees who share their faith and for the provision of services to their members and adherents. Progressive and secular audiences are generally receptive to the argument that when religious institutions are using private funds donated to them for the furtherance of sacred purposes, they should be able to limit the use of those funds to only those activities and individuals engaged in that mission. When public funds are at issue, however, this argument is not only unpersuasive but counterproductive. Public funds granted to religious institutions to further secular, public purposes should not be limited to the beneficiaries or employees of a particular faith.

Second, I suggest, based solely on anecdotal evidence (but that includes a lot of talks to a lot of secular and/or liberal audiences and various advocates and advocacy groups for a lot of years), that few arguments have been as effective inarguing for the distinctive treatment of religion for free exercise or statutory accommodations purposes as the argument that the distinctiveness of religion is recognized and taken into account for establishment clause purposes as well. In part, this argument suggests that whatever privileges religious individuals and institutions allegedly receive as a result of exemptions and accommodations are offset by establishment clause constraints that disadvantage religion by limiting the support it can receive from the state. The argument also helps to justify the basic idea that there is something special about religion that warrants distinctive treatment by government. Obviously, when private religious institutions receive the same financial support as private secular institutions, this argument is substantially undermined.

Third, fairly or not, progressives see religious institutional claims for comparable access to government funding alongside claims for special exemptions that are unavailable to their secular counterparts as an attempt to game the system. It is an attempt to have one’s cake and eat it too. Religious institutions seem to be arguing that the programs they operate are secular in nature, and accordingly, they should be eligible for government financial support on the same terms as secular applicants for funding. Yet at the same time, religious institutions are arguing that their programs are intrinsically religious and as such require exemptions and accommodations unavailable to their secular counterparts.

For example, consider a claim by a preschool operated by an adjacent church for state financial support for its playground, a hypothetical that is roughly analogous to the facts of the Trinity Lutheran Church case, currently before the Supreme Court. The church argues that that the playground is a secular activity. By supporting it, the state is not funding religious instruction, worship, or proselytizing. Accordingly, the church should have the same access to state funding as secular institutions, such as secular preschools with playgrounds. Now suppose the church also argues that unlike its secular counterparts, (1.) it should be permitted to discriminate on the basis of religious belief and conduct in hiring employees—including playground monitors and maintenance staff; (2.) it should be permitted to discriminate on the basis of the religious belief and conduct of families in admitting their children as students—even if most of what the students do is to play on the playground; (3.) it should be provided additional discretion in designing its playground/curricular activities; (4.)it should be protected against certain burdensome land use regulations (because religious but not secular land uses receive special protection under RLUIPA, the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act). Progressives are not alone in wondering why and how a church preschool playground can be characterized as secularfor the purpose of determining its eligibility to receive government funds and religious for the purpose of determining its entitlement to special accommodations.

I see no easy answers to how these conflict areas can be resolved to promote consensus support for religious liberty and equality. This article is not nearly so ambitious. Its goal is only to take the first step of identifying the nature and scope of the problem. I do think the utility of religious liberty arguments for the progressive concerns I described in Conflict 2 has the potential to help restore progressive respect for religious liberty to some extent. On the other hand, should conservatives reject religious liberty claims that resonate with progressive values while insisting on protecting religious liberty when conservative values are at risk, the possibility of increased consensus will almost certainly diminish.

Article Author: Alan E. Brownstein

Alan E. Brownstein, a nationally recognized Constitutional Law scholar, teaches Constitutional Law, Law and Religion, and Torts at UC Davis School of Law. While the primary focus of his scholarship relates to church-state issues and free exercise and establishment clause doctrine, he has also written extensively on freedom of speech, privacy and autonomy rights, and other constitutional law subjects. His articles have been published in numerous academic journals, including the Stanford Law Review, Cornell Law Review,UCLA Law Review and ConstitutionalCommentary. In 2008, Liberty was privileged to recognize Professor Brownstein for his passion and dedication to religious freedom at its annual Religious Liberty Dinner in Washington, D.C.