When Religious Liberty Issues Aren’t

Clifford R. Goldstein January/February 2013Unlike my immediate predecessor, Roland Hegstad, who edited Liberty for 34 years, or my immediate successor, Lincoln Steed, who has been at the helm about 14 years and counting, my stint as Liberty editor was short: only seven.

In that time, though, I faced a rather interesting phenomenon. Because Liberty is a church publication defending religious freedom, every now and then I'd hear from an irate church member who wanted us to come to his or her defense. Why? The reasons varied, but were, generally, of the following nature: Their favorite dissident speaker was denied the pulpit by the church board. Or they were "unfairly" denied a church office. Or the pastor was preaching "error." Or this person should have been ordained and wasn't. Or they didn't like the church's position on some social issue.

However valid (or not) their complaint, I always tried to explain that our department wasn't the right place to come with their grievance. Sure, their issue dealt with religion and involved a dispute, but those two factors alone didn't necessarily make it a religious freedom issue any more than a Muslim arguing with a Christian over the identity of Jesus would necessitate calling in Homeland Security.

What, then, is or is not a bona fide religious liberty question?

Free Associations

Back in the mid-1980s, while writing for Liberty, I did an article about a dispute within the Roman Catholic Church regarding 97 dissident Catholics, including 24 nuns, who had run afoul of then-Pope John Paul II's wrath. They had signed a manifesto in defense of abortion and thus faced disciplinary measures. The question arose about whether or not the church could discipline the nuns, and even throw them out of their orders, and if so, could or should the nuns take legal action. In the end I basically sided with the pope, not on the question of abortion (which was another matter), but on the right of a church to discipline its own members, or, in this case, to discipline those who took orders. I quoted a couple of well-known U.S. Supreme Court cases in which the High Court basically said it was not the business of the secular authorities to interfere with internal church issues.

This concept gets to the heart of religious liberty and church-state separation. In essence, people who join churches do so voluntarily. They are there of their own free will. They are not forced to join, and certainly not by the state. By joining a church, one publicly associates oneself, to some degree, with the teachings, mission, and goals of that church. What makes that membership meaningful is, however, the free association with that body. That association, and the public proclamation that comes merely by linking oneself to the name of the church, has potency only because one has freely chosen it. Forced membership would all but denude that proclamation of any public witness, of any testimony, public or private, regarding your convictions. You would be there because you had to be, not because you necessarily believed in what the church stood for.

John Locke, one of the patriarchs of religious freedom, wrote in 1698, in the context of religious liberty, that "I may grow rich by an Art that I take not delight in; I may be cured of some Disease by Remedies that I have not faith in; but I cannot be saved by a Religion I distrust, and by a Worship that I abhor."

Biblical Freedom

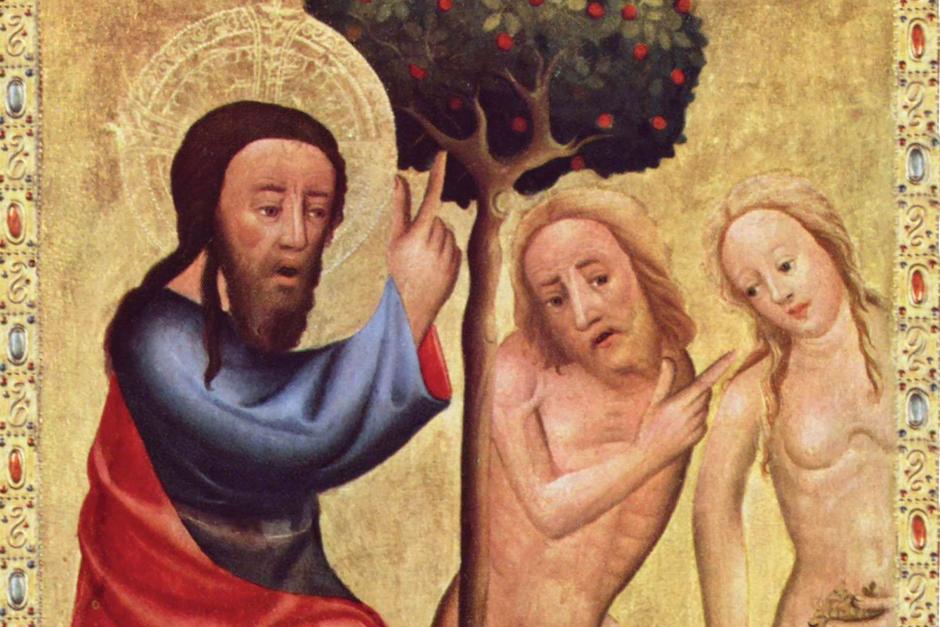

Locke touched on a crucial point: Only a faith, or by extension one's affiliation with a church, freely entered into, is of value; which explains why the principle of religious freedom is found all through the Bible, even in the Old Testament. In Eden, for instance, Adam and Eve were given free choice whether or not to obey. "And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, Of every tree of the garden you may freely eat: but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die" (Genesis 2:16, 17). Though eating of the tree would come with consequences, they weren't forced to obey the command.

After all, why would the Lord have commanded Adam not to do something unless Adam had the potential to do it? The command itself presupposes Adam's freedom; otherwise, why give the order to begin with? Thus, amid the luxuries of the Garden Paradise, God gave Adam and Eve a simple test, which makes no sense for nonfree beings, wired only to obey and do what is right. Adam was free, an autonomous moral being with the capacity to choose right and wrong. It had to be that way, because forced obedience would be as meaningless as adhering to "a Religion I distrust, and by a Worship that I abhor."

No one better revealed this truth than did Jesus, who, though having the right to force obedience, never did. As God, as the Creator (Colossians 1:16), as the great "I am" (John 8:58; Exodus 3:14), He is the source of everything created (John 1:1-3). All that we are, or ever could be, comes from the One in whom "we live, and move, and have our being" (Acts 17:28). As such, He alone deserves our worship and our obeisance. Yet if He didn't force either, what gives any human authority the right to? God didn't create humans free only to come thousands of years later and trample upon that freedom Himself, or use the state to do it for Him. On the contrary, it was the state, and the power of the state, under the instigation of religious authorities, that led to Christ's death. Right there in the story of Jesus, then, we have an archetype of just how dangerous the melding of church and state can be.

Hence, Thomas Jefferson knew exactly what he was talking about when he wrote that God, though "being Lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate it [religion] by coercions on either, as was in His Almighty power to do." Though God has the power, and perhaps the right, to force us to obey, He doesn't, and so neither should humans. To do so, Jefferson said, would be "a departure from the plan of the Holy Author of our religion." In short, a religion that is forced is not just useless but is contrary to the very principles of God's government itself.

The Power of the State

Now, God might not use force, but caesar does. Caesar is supposed to use force; that's his job. Sure, it would be nice if all citizens obeyed the laws?traffic laws, tax laws, environmental laws, and every other law?out of the goodness of their hearts. But the fact is, most people don't; they have to be forced, threatened by civil or criminal penalties for violation of those laws. This is the essence of a state: It has not just the power to punish, but also the prerogative to do so.

Of course, the laws it enforces, and the punishments it metes out in enforcing those laws, can be unfair, cruel, and arbitrary. But that's not the point. The point is that the state, to function as the state, to even be a state, has to use the threat of force, and even force itself. It wouldn't be a state otherwise.

Faith must not, and cannot, come by force, and because the essence of the state is force, we arrive at the genius behind the whole concept of church-state separation. One realm, the spiritual, by its very nature, must not use coercion; the other realm, the state, by its very nature, must. Thus, the safest course is to keep both realms as separate as possible.

Church Battles

All this leads to the gist of what constitutes true religious freedom issues, and why I would, as Liberty editor, often tell those church members who wanted to drag us into their church disputes, "Sorry, wrong department."

Why? Because as already stated, at the most fundamental level, church affiliation is voluntary. You freely choose to be part of that body. The state, and the power of force it wields, has nothing to do with your membership. If something happens that you deem unfair, you are as free to leave that church body, just as you were to join. As long as no state coercion is involved, it's not a religious liberty issue in the classic sense.

However legitimate your complaint, it's not like the Amish, who decades ago faced state coercion over how they educated their children. It's not like Jehovah's Witnesses, who felt the power of state in regard to saluting the American flag. It's not like the Santeria cult in Florida, who faced the state trying to restrict their free exercise of religion. It's not like some Baptists, who felt state wrath in regard to where they worshipped. It's not like some Seventh-day Adventists, who felt state wrath over Sunday blue laws. In short, maybe a person has a legitimate gripe and has been unfairly treated, but most likely when he or she calls the Religious Liberty Department about an internal church squabble, they won't get much help from the Religious Liberty Department (in our church, there are other avenues, though).

Gray Areas

Of course, as with most things in life, especially church-state things, the issues are not always so clear-cut. Though the courts have been reluctant to allow the power of the state to get involved in internal church disputes, they occasionally do. One of the first articles I edited as Liberty editor dealt with the distribution of assets after a church split. In cases in which property is involved, or a crime has been alleged (such as child abuse), the state will get involved because?unlike the pastor's "heresy," or one's favorite dissident being denied the pulpit?these are legal issues and, hence, often fall under the purview of the state and its coercive power. Also, in matters of employment, especially when people are fired, the issue can get much more complicated, and the state might get involved. Finally, despite Paul's clear-cut counsel against Christians taking one another to court (1 Corinthians 6), in our hyperlitigious society Christians are constantly suing each other or their churches over just about everything, thus often having (contra Paul) "unbelievers" (verse 6), with the power of the state, settle these disputes.

It's been many years since I left the Liberty editorship, so I haven't been privy to the myriad issues that always arise in the complicated area of church-state separation since then. But if the past is precursor, I've no doubt that my worthy successor, Lincoln Steed, has received many phone calls from irate church members claiming their religious liberty has been violated by the church and thus demanding that he do something about it. I don't know what he says, but I'm sure it's something similar to what I'd reply, which was "Sorry; wrong department."

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.